At a time when Congressional ineptitude is at an all-time high (and approval ratings concomitantly low), I’d like to see as little Congressional influence over the highest echelons of U.S. national security policy as possible. One case in point is the increasingly delicate situation with Iran. The last round of talks fizzled after a surprise interjection by the French over the final terms of a historic deal. The give-and-take in any Iran deal would see the United States offer sanctions relief for a cessation of enrichment activity on the Iranian side (among other concessions).

For a deal to work here, the President needs authority to credibly lift the sanctions after a deal with Iran – which he thankfully has … for now.

So what is Obama’s ace-up-the-sleeve on Iran? The “national security waiver”. In late October, before the latest round of failed P5+1 talks in Geneva, Yochi Dreazen wrote in Foreign Policy that “the White House has tremendous leeway to decide how strictly they get enforced.” The national security waiver allows for a temporary softening or lifting of sanctions via executive mandate – something that has to date been employed to offer waivers to U.S. allies for energy commerce. For example, Japan and certain European Union allies of the United States have received leeway from the White House on their commercial activities with Iran. The national security waiver has been a remarkably flexible tool for the White House in conducting its diplomacy with Iran – but that may be changing.

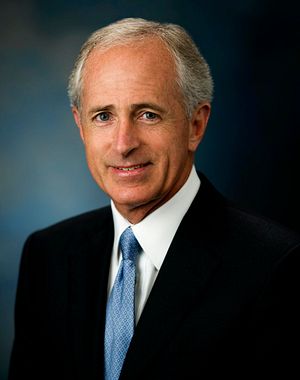

Astute readers will point out that it has been Congress that has spent the past few years imposing increasingly tougher sanctions on Iran. Indeed, even after Hassan Rouhani’s election and his so-called “charm offensive,” the House voted 400 to 20 at the end of July to strenghten sanctions. The trend continues. Against the backdrop of the P5+1 Geneva talks last week – and to this very day – Sen. Robert Corker (R-Tenn.) has been campaigning for a new round of sanctions on Iran. Corker’s ultimate objective is to disable an Iranian deal until Iran acquiesces to a very harsh set of terms as part of a deal – something it is highly unlikely to do. Corker is aware of how damaging this could be to the current process towards an interim deal, saying his measures "would keep an interim deal from happening unless there is actual tangible changes that take place."

The threat is rather credible this time and has broad bipartisan support from both Democrats and Republicans who are hawkish on Iran. Within Congress, appearing strong on Iran, if framed with a heavy concern about Israeli security, is a low-cost political maneuver that wins votes from several constituencies. Leaving aside the intractably hawkish Republican contingent against Iran, consisting of figures such as Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) and Sen. Lindsey Graham (R.-SC), Democrats are unwilling to throw their force behind the White House on Iran. Rep. Steve Israel (D-NY), chair of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, told Foreign Policy that "If the president were to ask for a lifting of existing sanctions it would be extremely difficult in the House and Senate to support that.”

Another complicating factor is that Corker has considered including his proposal as an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) – a piece of legislation that is critical to pass and sets military and defense policy for the entire fiscal year. The prospects of a White House veto on an NDAA bill containing such an amendment would likely be slim.

For the moment, the President has communicated the necessity of the national security waiver to members of Congress, who are unlikely to take heed. If Bob Corker has his way, the United States could find itself in an embarrassing situation where it manages to make a deal with Javad Zarif and his team, only to find that it can’t make good on its promises due to a Congressional roadblock. There is a time and place for domestic politics to play a role in the conduct of foreign policy – this isn’t one of them.