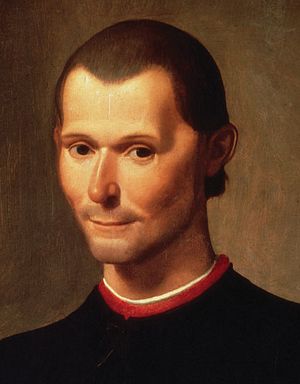

In his Discourses on Livy, the great Niccolò Machiavelli opines that the timber of humanity primes us to repeat what worked last time. Our minds run in grooves. This can prove dangerous, he maintains, because good fortune rewards those who vary with the times while punishing those who get behind the times. The Florentine statesman postulates two reasons why people find it hard to conform to changing surroundings. One, “we are unable to oppose that to which nature inclines us.” We’re hardwired to think, feel, and act in certain ways. And two, “when one individual has prospered very much with one mode of proceeding, it is not possible to persuade him that he can do well to proceed otherwise.” We extrapolate from, and act on, a very small sample size of personal experiences.

Machiavelli’s is a fancy Renaissance forerunner to an old American saying: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Success then translates into success today. Right?

Well, maybe. Now think about big institutions, bodies made up of — and led by — individuals prone to linear thinking. Institutions like governments, armed services, and companies tend to transcribe dramatic events — great victories or traumatic defeats — into bureaucratic routine. Structuring policies, doctrines, and career incentives on the assumption that past triumphs can be rerun or setbacks avoided strips flexibility out of decisions and actions. For Colonel John Boyd, the lenses through which an individual or organization interprets the past color, and can inhibit, the ability to orient to new surroundings.

In short, it’s hard to keep up with changing circumstances. As Machiavelli counsels cheerily, ill fortune befalls those who fail to keep up with the times.

This tendency to stamp the lessons of the past onto present practice is a recurring theme in our Naval War College courses. George Washington and his fellow Revolutionary commanders thought they could replay the Battle of Bunker Hill over and over again. They could build fixed defenses and British Redcoats would charge them in costly frontal assaults. The British Empire would batter itself into submission. Wrong. Imperial Japanese leaders predicated their maritime strategy for World War II on rerunning the 1904 surprise attack on Port Arthur and the decisive 1905 encounter with the Russian Navy at Tsushima Strait. But the United States wasn’t Imperial Russia. Japanese strategy came to grief because Tokyo fell out of step with the times.

What to do? Changing routines may require changing out personnel with older ways of thinking for those with unorthodox — yet more accurate — views of the setting. It demands flexibility, and a measure of humility on the part of top leadership. Machiavelli attributed Rome’s eventual victory over Hannibal in large part to its ability to change commanders when the situation changed. The city had Fabius the Delayer for the defensive phase of the protracted struggle. But Fabius proved unable to break out of his defensive mindset. He failed to see when Rome had amassed enough strength to take the offensive. Roman leaders, however, could pick an enterprising leader, Scipio Africanus, to carry the fight across the Mediterranean. Rome won big.

So if you need to innovate, it’s good to be a republic. It affords a degree of strategic agility seldom seen in authoritarian or totalitarian states. It behooves leaders of all stripes to keep their organizations as flexible as possible, preserving and extending their advantages over more hidebound competitors. The capacity to adapt, then, constitutes a crucial metaphysical edge. If the United States and its allies want to compete effectively with the Chinas and Irans of the world, they could do worse than study their Machiavelli. Nimble is as nimble does.