How many Indian Prime Ministers have been born in independent India?

If you said “none so far,” you’re right.

Despite the trivia night appeal of that little fact, it reveals a trouble feature in Indian democracy – India’s leaders are old, and unrepresentatively so for a nation that prides itself on democracy. As per the 2011 Indian Census, the average Indian is 25 years old whereas his average legislative representative is a good 40 years older, at 65. The five dollar word describing this condition is “gerontocracy” – rule by the elders. It’s an old idea too: Plato wrote in The Republic, “it is for the elder man to rule and for the younger to submit.”

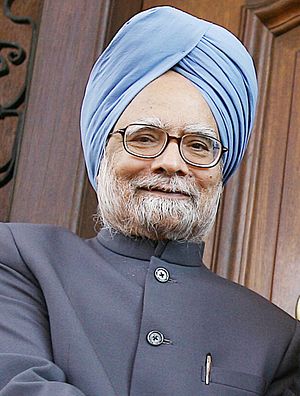

Of course, it’d be unfair to leverage this argument against India exclusively; after all, all societies, democratic or authoritarian, are ruled by older-than-average-age men (usually). The Indian case is simply far more extreme than most democracies, certainly within the G20. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, at 81 years old, has the odious honor of being the oldest and only octogenarian democratic leader in the G20 (King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia tops things out at 89 years old; alas, Silvio Berlusconi would be up there at 77 had he not fallen from grace – he certainly lives youthfully). Singh’s cabinet is similarly composed of a coterie of septuagenarians and “youthful” ministers in their 60s.

Folk wisdom in India has it that former Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao, then in his 70s, was taking an afternoon nap as riots unfurled around Babri Masjid in Uttar Pradesh. The ensuing failure of the executive to respond decisively was attributed to the Prime Minister’s age, which was seen to inhibit his capacity to tackle new challenges with vim and vigor.

The United States’ founding fathers, a group consisting of the 18-year-old James Monroe, 20-year-old Aaron Burr, 21-year-old Alexander Hamilton, and 25-year-old James Madison (ages as of July 4, 1776) saw it fit to include age requirements for legislators and the president. These wise young men saw the benefits that age can bestow upon a leader. A seasoned general or president behaves differently from a wunderkind (the Kims of North Korea might be the exception here).

Indians have a life expectancy of 65 years and the retirement age for the civil services are set at 60 years. Why then are its leaders so much older? Explanations are numerous, including the dynastic tendencies of the entrenched Indian National Congress leadership, a cultural proclivity to respect the elderly despite their competencies, and matter of parliamentary procedure, including the tendency of Indian political parties to nominate their own leaders. The Economist observes that autocracies, far more than democracies, are likely to have a vast gap between the age of the average citizen and that of her leaders – India being a major exception. Egypt, a poster child of Arab spring, which deposed 82-year-old Hosni Mubarak, has an average age of 24.

The gerontocracy issue isn’t alien to Indians – there is somewhat of a national debate on the issue of enforcing a retirement age. The good news is that things look to be changing. One of the more disruptive and less talked about aspects of the much hailed Aam Aadmi Party’s (Common Man’s Party) impact on Indian politics is that it actually manages to be more representative of the aam aadmi’s age than the Indian National Congress or BJP. Arvind Kejriwal, who supplanted the 75 year old Sheila Dikshit as the Chief Minister of Delhi, is lithe and dynamic at only 45-years-old. One suspects that the surge in democratic participation rates, at least as seen in the recent assembly elections, will amplify the voice of the youth in Indian politics, who may prefer younger, more dynamic politicians to their older counterparts.

On the national level, the good news is that whoever wins the general elections – be it Narendra Modi for the BJP or Congress Party scion Rahul Gandhi – India will finally have a Prime Minister born in the independent Indian Republic. For a country so young, with so much to look forward to in terms of growth, the way forward necessitates a shared vision and ethos between the people and their leaders – closing India’s gerontocratic age cap is crucial to this end.