From a obnoxious perceptive Naval Diplomat correspondent comes this query: “why does it seem that Thucydides and the Peloponnesian War dominate the analogy market for U.S.-China relations, to the detriment of the Punic Wars?” He, she, or it goes on to note that the conflicts between Rome and Carthage feature “a lot of parallels, with an established power, a rising power, a zone of clear conflict, accidental escalations, and the like, not least of which was the role played by sea power.”

Gotcha! Come, let us speculate together. First of all, let’s not limit Thucydidesmania to U.S.-China relations, or to the present day. His History of the Peloponnesian War has long been classical antiquity’s go-to fount of wisdom, not just for China hands today but for pundits, learned statesmen, and warrior gods across the ages. For instance, Thomas Hobbes, best known as the author of Leviathan (1651), was the first to translate Thucydides into English (1628). After spending so much time immersed in the bloodletting between Athens and Sparta, it’s small wonder Hobbes came to see the “life of man” as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” A ray of sunshine, that Hobbes.

Nor was Thucydides just an English fad. In 1777, as the American Revolution raged, founding father (and future president) John Adams advised his son (and future president) John Quincy Adams to study war. Wrote the elder Adams, “There is no History, perhaps, better adapted to this useful purpose than that of Thucydides….” He urged John Quincy to make himself the “perfect master” of Thucydides’ History “in his own tongue.” For help he should consult the Hobbes translation found in the family library while searching out the “more elegant” translation from English clergyman William Smith.

Adams’s contemporaries — the likes of George Mason, Alexander Hamilton, and Benjamin Franklin — also studied Athens as they sought to fashion a political regime that allowed Athenian-style dynamism while keeping Athenian-style democratic excesses in check. Thucydides, then, is an indirect forefather of the American mixed regime. His ghost is smiling.

Nor was this just a founders’ thing for Americans. After World War II, General George C. Marshall, perhaps the greatest soldier-statesman of the 20th century, told an audience in Princeton, New Jersey that no one could comprehend the dilemmas besetting the postwar world “who has not reviewed in his mind the period of the Peloponnesian War and the Fall of Athens.” So it’s nothing new for Athens to ace out Rome as a source of political and strategic insight.

But this is largely an appeal to authority, isn’t it? If eminent people prefer Greek to Roman antiquity, that must be because Greek history is more interesting and enlightening. Right? Not necessarily. Methinks the storyteller, not the story, is what keeps seekers of wisdom coming back to the Peloponnesian War. As my able correspondent alludes, it’s not so much that Greek is richer than Roman history. It’s that there was no one with the stature of a Thucydides to retell the drama and deeds of Roman antiquity, and to extract the takeaways for readers.

Now, for my money, Machiavelli’s Discourses do rival Thucydides’ History. In effect Machiavelli uses Titus Livy’s writings about the Second Punic War as the fundamental research for a lengthy commentary on politics and strategy. It’s probably no accident that some, ahem, more ornery types lobby constantly to insert Niccolò’s works into the curriculum in Newport. If those nameless insurgents succeed, Roman analogies may pop up more often.

Thucydides, nevertheless, remains unique in that he combines history, political philosophy, and strategic theory into a single accessible treatise. Even Herodotus, the crazy uncle of history, didn’t pull that off. And no historian of Rome — not Livy, nor Tacitus, nor Polybius, nor Gibbon, nor even Machiavelli — quite managed to compose a “possession for all time,” as Thucydides immodestly but accurately styles his History.

But there is a downside to Thucydides’ economy of words, and to his willingness to pronounce upon great events. Namely, these virtues make him the political scientist’s classical historian. Looking for an erudite way to analyze the situation in the Western Pacific? Just excerpt Thucydides’ claim that the true cause of the Peloponnesian War was the rise of Athens and the fear it inspired in Sparta, the reigning hegemon. Ergo, we have … the “Thucydides Trap,” a geopolitical current supposedly sweeping the United States and China along toward conflict.

Well, maybe. Or maybe not. Not every ambitious power on the make comes to blows with the established power of the day. One hopes commentators on international affairs will school themselves in history and philosophy, as Henry Kissinger counsels sagely. That will help them resist the temptation to cherrypick passages from the classics. Let’s use history with discretion rather than succumb to bad habits.

Last point on this subject (for now). The Punic Wars dropped out of the Naval War College curriculum some years back, sometime in that void between when I left the College in 1996 and returned in 2007. But certain timeless insights endure around here. For example, Alfred Thayer Mahan reported getting the idea for his research on sea power from perusing Theodor Mommsen’s History of Rome on shore leave in Lima, Peru. He wondered how the Punic Wars would have unfolded differently had Rome commanded the sea early on. While Mahan commented on Athens and Sparta, it took Rome and Carthage to strike that first intellectual spark.

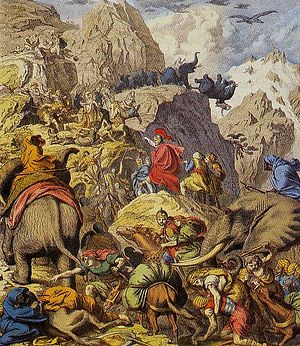

Or, the figure of Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus Cunctator is a fixture in the classroom. As retold in Polybius’ account, the Roman dictator Fabius mastered the art of clinging to Carthaginian general Hannibal’s armies while refusing to fight a decisive battle — a battle that might cost Rome everything if it lost. Instead Fabius’ army loitered near the Carthaginians, “goading their sides, in a desultory teasing way” (Alexander Hamilton’s words) while frustrating Hannibal’s bid for complete conquest of Italy.

Stalling for time gave Rome, the home team, the time it needed to muster superior resources, drive Carthage from the peninsula, and carry the fight across the Mediterranean into North Africa. Such offensive-defensive methods earned Fabius the nickname “the Delayer,” while helping to inspire such commanders as George Washington.

But the insights gleaned from such episodes are mainly operational in character, without a Thucydides to place them in their grander political, strategic, and even moral context. They resonate less with foreign-policy specialists. Nor are the Punic Wars fully satisfactory as a historical case, if only because posterity doesn’t know the Carthaginians as well as it knows the Athenians, Spartans, Persians, and myriad other protagonists in the Peloponnesian War. Historical forgetfulness is what happens when the victor razes an enemy’s homeland to the ground and salts the ruins — as Rome did.

Historians Richard Miles and Adrian Goldsworthy have put out nifty books about Carthage in recent years, so these sad times may be a-changing. One hopes so. Aegean history offers a rich vein to mine for historical lessons. But it’s not the only source of ore from the ancient world. Beware, China, lest Western strategists consult a hypersecret new manual of statecraft … Livy’s The War with Hannibal!!!