On Thursday, China’s state-owned Xinhua News Agency unveiled an ongoing feature entitled “New Silk Road, New Dreams.” The series promises to “dig up the historical and cultural meaning of the Silk Road, and spread awareness of China’s friendly policies towards neighboring countries.” The first article [Chinese] was titled “How Can the World Be Win-Win? China Is Answering the Question.”

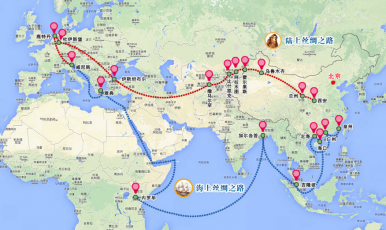

The Xinhua series promises the clearest look so far at China’s vision for its Silk Road Economic Belt as well as the Maritime Silk Road. One of the most intriguing pieces released Thursday was a map showing China’s ambitious visions for the “New Silk Road” and “New Maritime Silk Road.” It’s the clearest vision to date of the scope of China’s Silk Road plan.

According to the map, the land-based “New Silk Road” will begin in Xi’an in central China before stretching west through Lanzhou (Gansu province), Urumqi (Xinjiang), and Khorgas (Xinjiang), which is near the border with Kazakhstan. The Silk Road then runs southwest from Central Asia to northern Iran before swinging west through Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. From Istanbul, the Silk Road crosses the Bosporus Strait and heads northwest through Europe, including Bulgaria, Romania, the Czech Republic, and Germany. Reaching Duisburg in Germany, it swings north to Rotterdam in the Netherlands. From Rotterdam, the path runs south to Venice, Italy — where it meets up with the equally ambitious Maritime Silk Road.

The Maritime Silk Road will begin in Quanzhou in Fujian province, and also hit Guangzhou (Guangdong pronvince), Beihai (Guangxi), and Haikou (Hainan) before heading south to the Malacca Strait. From Kuala Lumpur, the Maritime Silk Road heads to Kolkata, India then crosses the rest of the Indian Ocean to Nairobi, Kenya (the Xinhua map does not include a stop in Sri Lanka, despite indications in February that the island country would be a part of the Maritime Silk Road). From Nairobi, the Maritime Silk Road goes north around the Horn of Africa and moves through the Red Sea into the Mediterranean, with a stop in Athens before meeting the land-based Silk Road in Venice.

The maps of the two Silk Roads drive home the enormous scale of the project: the Silk Road and Maritime Silk Road combined will create a massive loop linking three continents. If any single image conveys China’s ambitions to reclaim its place as the “Middle Kingdom,” linked to the world by trade and cultural exchanges, the Xinhua map is it. Even the name of the project, the Silk Road, is inextricably linked to China’s past as a source of goods and information for the rest of the world.

China’s economic vision is no less expansive than the geographic vision. According to the Xinhua article, the Silk Road will bring “new opportunities and a new future to China and every country along the road that is seeking to develop.” The article envisions an “economic cooperation area” that stretches from the Western Pacific to the Baltic Sea.

Despite this expansive goal, it’s not quite clear yet exactly what will tie together the disparate countries along the New Silk Road (both on land and at sea). China has discussed building up infrastructure (especially railways and ports) along the route, yet the Xinhua article specifically says the vision includes more than simply speedy transportation. China envisions a trade network where “goods are more abundant and trade is more high-end.” Beijing expects the economic contact along the Silk Roads to boost productivity in each country. As part of this vision, China has repeatedly stressed its economic compatibility with many of the countries along the planned route, and offered technological assistance to countries in key industries.

China also envisions the Silk Road as a region of “more capital convergence and currency integration” — in other words, a region where currency exchanges are fluid and easy. Xinhua notes that China’s currency, the renminbi, is becoming more widely used in Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, and Thailand. Yet the article does not call for the renminbi to become the Silk Road’s primary currency, but rather hopes that local currencies will be the dominant means of economic deals.

From economic exchanges, China hopes to gain closer cultural and political ties with each of the countries along the Silk Road — resulting in a new model of “mutual respect and mutual trust.” The Silk Road creates not just an economic trade route, but a community with “common interests, fate, and responsibilities.” The Silk Road represents China’s visions for an interdependent economic and political community stretching from East Asia to western Europe, and it’s clear that China believes its principles will be the guiding force in this new community. “China’s wisdom for building an open world economy and open international relations is being drawn on more and more each day,” Xinhua wrote.

But for all the ambitious talk, details remain scarce on how this vision will be implemented. Will the land- and sea-based Silk Roads be limited to a string of bilateral agreements between China and individual countries, or between China and regional groups like the European Union and ASEAN? Is there a grander vision, such as a regional free trade zone incorporating all the Silk Road countries? Or will China be the tie that binds it all together, with no special agreements directly linking, say, Kazakhstan and Germany?