It’s astonishing how one errant word or metaphor can disarm readers’ or hearers’ critical faculties. Exhibit A: Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel’s citing the War of 1812 as a precedent for the U.S. Army to integrate coastal defense into its post-Afghanistan, post-Iraq slate of missions.

The War of 1812 reference made Hagel the butt of countless jokes. Military wags roundly lampooned the secretary for deriving guidance for today from such an antiquarian reference. After all, today’s ultramodern U.S. military has little to learn from its early history. Right?

Well, no. It’s not right at all. The substance of Hagel’s remarks was mostly lost amid the wisecracks. In reality, what he proposes makes eminent good sense for groundpounders searching for their identity in maritime Asia.

What do listeners hear when someone draws the War of 1812 analogy? Two things, it seems. One, that the person drawing the analogy sees a United States defending its immediate environs against an outside, far stronger maritime power. It’s not a globe-straddling superpower. It’s a local power trying feebly to protect its shores. No serious thinker would pattern contemporary methods on such a lackluster precedent.

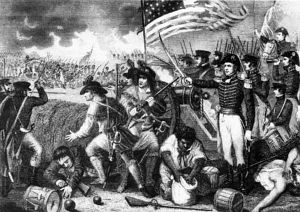

And indeed, Britannia, faraway but overpowering, ruled the waves — including the waves lapping against the eastern seaboard of North America — during that half-forgotten conflict. Its Royal Navy imposed a stifling blockade on the new republic, squelching seaborne trade almost wholly by 1814. Having won a spate of inspiring single-ship victories in the opening months of the war, the U.S. Navy found itself largely confined to port. Worse, the Royal Navy landed amphibian forces along the Chesapeake Bay. Redcoats burned the presidential mansion, later the White House, late in 1814. Some precedent.

And two, that the speaker would trust rudimentary, largely passive, ineffective defenses to ward off stronger opponents. Strike two! The founding-era U.S. Army and Navy, their political masters, and Congress placed their hopes in short-range coastal artillery — all gunnery was short-range in yesteryear, with combat reach under five nautical miles — and gunboats to hold enemies at bay. That was homeland defense on the cheap, befitting a nation loath to levy taxes to fund a battle fleet to mount a forward high-seas defense. This approach availed little, as naval historians Theodore Roosevelt and Alfred Thayer Mahan pointed out in their chronicles of the War of 1812 at sea.

Like today’s wags, TR and Mahan ridiculed the idea of land-based coastal defense. They wanted to send the fleet, and presumably would have sent its air arm as well once naval aviation became a going concern. The good news is that Secretary Hagel wasn’t talking about withdrawing from the world or reverting to the brave old world of coastal artillery. He was talking about equipping and training the U.S. Army to shape events at sea from shore, in distant theaters like the Western Pacific and China seas.

Shore-fired weaponry has come into its own since the age of coastal-defense proponents Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and James Madison. Using long-range precision weaponry such as truck-launched anti-ship and anti-air missiles may be coastal defense. But it’s an intensely offensive-minded brand of coastal defense, capable of pummeling ships and planes throughout large volumes of sky and sea.

Far from pushing obsolescent concepts that never worked in the first place, then, Hagel was looking backward to look ahead. What else is history for? The Naval Diplomat approves of such warmaking methods, and indeed has touted them for some time. So should you.

Save the mockery.