Earlier this week, Indonesia and China held their first ever high-level bilateral economic meeting. The meeting, chaired by Chinese State Councilor Yang Jiechi and Indonesian Coordinating Minister for Economics Sofyan Djalil, is part of an effort to concretize their comprehensive strategic partnership under the new administration led by President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo.

Sino-Indonesian relations had already strengthened considerably both symbolically and substantively under the Yudhoyono years, in spite of their inherent limitations. Trade quadrupled to $66 billion and investment increased to $2 billion as both countries went from strategic partners in 2005 to comprehensive strategic partners in 2013. People-to-people relations have also expanded appreciably, while military ties have advanced, albeit at a more cautious level (as might be expected).

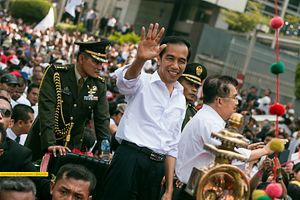

From the get-go, Jokowi signaled that his approach to Sino-Indonesian relations would be much more concrete than that of his predecessor. During his first encounter with Chinese president Xi Jinping on November 9 last year, Jokowi bluntly stated that he wanted the relationship to “materialize into more concrete outcomes.” Pressed on what those outcomes might be, he said he wanted more progress in trade and investment and would like Chinese companies to be more involved in infrastructure development.

Since those remarks, things have gradually begun to take shape. Later that month, Indonesia joined the Chinese-led Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), even though Jokowi did not get his wish for the AIIB to be based in Jakarta. Indonesian and Chinese officials have also been discussing how Jokowi’s global maritime fulcrum doctrine can potentially complement Beijing’s 21st Century Maritime Silk Road idea – including the building of ports and tollways in Indonesia. And at their economic meeting, Yang and Sofyan both agreed to expand two-way trade and enhance cooperation in major infrastructure, with a specific focus on power plant cooperation.

But as is often the case in China’s relations with Southeast Asian countries, there is more than meets the eye. For one, too often trade and investment pledges are not actually followed through on. Last week, Indonesia’s Investment Coordinating Board (BKPN) said that only 6 percent of Chinese investment in Indonesia had actually materialized, putting it in 13th place, below the Netherlands, Mauritius, and – embarrassingly – even Taiwan. While gaps between proposed and realized investments are quite common for those who monitor such statistics, this is a pretty huge one.

As for infrastructure, as I have argued previously, there is a bit of a Catch-22 in that attracting foreign investment from countries like China hinges on whether Jokowi can accomplish some of his domestic reforms, but those domestic reforms may require foreign investment to succeed in the first place. To his credit, some moves have already been taken to improve the country’s regulatory environment, including the official launch of the one-stop investment licensing service earlier this week. But there is much more that needs to be done in this regard.

It would also be a mistake to view the Sino-Indonesian relationship purely from the prism of economics. There is still lingering distrust in Indonesia toward China – a product of historical and contemporary factors – that tends to spill over into economics realm as well and serves to limit the upward trajectory of ties. More specifically, the strident tone the Jokowi administration has adopted on sovereignty and territorial integrity could also complicate things in the economic dimension. Chinese vessels have thus far escaped Indonesia’s ‘sink the vessels’ policy to eradicate illegal fishing, which I have reported on extensively. But with Jakarta already confiscating more than nine vessels and recently revoking a 2013 bilateral agreement signed with Beijing on fisheries, it remains to be seen how long this will last.

Then there’s the specific issue of the South China Sea disputes. Indonesia is not a claimant – strictly speaking – because China’s infamous “nine-dash line” map overlaps with the waters around the resource-rich Natunas, rather than the islands per se. But it is no secret that Jakarta is nervous about this, which is why it is increasing its military presence in the South China Sea. That, combined with the Jokowi administration’s prickliness on sovereignty issues, could lead to friction farther down the line. More broadly, Jokowi has signaled that Indonesia intends to act as an “honest broker” on the disputes. If this manifests into more active involvement, it risks irking Beijing, which has repeatedly insisted that the disputes ought to be handled by the parties themselves – a self-serving demand that comports with its strategy to keep ASEAN divided.

It is still early days, however, and both sides are content to try and make progress. The BKPN says it plans on establishing a special unit focused on boosting Chinese investment, and that it expects Beijing to jump from thirteenth to third place soon. Chinese and Indonesian officials are also happy to talk broadly about the intersection of their maritime visions, even though it is quite clear where their interests diverge. Atmospherics might also facilitate things, as 2015 marks both the 60th anniversary of the historic Bandung Conference and the 65th anniversary of the Sino-Indonesian relationship, in addition to being China’s self-declared “Year of ASEAN-China Maritime Cooperation.” For now at least, Sino-Indonesian relations appear to have gotten off to a good start.