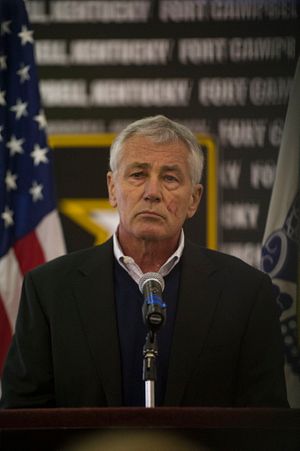

In a recent interview he gave to Stars and Stripes and Military Times, outgoing U.S. Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel reiterates his skepticism toward the use of U.S. military power in imposing American values abroad. “You cannot impose your will, you can’t impose your values, you can’t impose your standards, your institutions on other societies and other countries. It has never worked; it never will work, as noble as you believe [the effort] is,” he is quoted as saying.

This conclusion is partially based on his experience as an infantry soldier in the Vietnam War, as he explains: “The violence, the horrors, the suffering that I saw [in Vietnam] conditioned me … I saw the suffering of our own troops; I saw the suffering of the Vietnamese people; I saw terrible things, which war always produces.”

In addition, his personal experience of war, combined with the public experience of the American military, has him worried about “mission creep” — the slow militarization of U.S policy. The U.S. has been conducting large-scale counterinsurgency campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq with billions of DoD dollars spent (and often wasted) on non-traditional military assignments (e.g., institution-building). Hagel notes:

“It is easy to drift into other missions, and I do believe that you always have to ask the tough questions, [such as] what happens next? Where do you want this to end up, (…) Any secretary of defense has to always be on guard that we don’t inadvertently sometimes drift into a more accelerated use than we thought of what our military was going to be [doing] … I think the two long wars that we were in the last 13 years is pretty clear evidence of … how things can get out of control, and drift and wander.”

Hagel also repeatedly voiced his concern that the United States will continue to be engaged in drawn out conflicts with no end in sight.

His comments have drawn some criticism. Bing West, former assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs, offers the usual rebuttal of those who still believe that state-building and the promotion of American values done by the U.S. military can be successful:

“Hagel’s disdain for American foreign policy is selective. He ignores our performance in World War II, the rise of democracies in Germany, Japan, and South Korea, the creation of the United Nations, the law of the sea undergirded by the U.S. Navy, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and countless other indisputable successes. While of course he is entitled to his dissenting views, he should keep them private while he is a cabinet member.”

Even before becoming secretary of defense, Hagel’s basic mantra was to question all fundamental assumptions of U.S. defense and foreign policy. For example, as quoted by Bob Woodward, Hagel cautioned U.S. President Barack Obama: “’We are at a time where there is a new world order. We don’t control it. You must question everything, every assumption, everything they’ — the military and diplomats — ‘tell you. Any assumption 10 years old is out of date. You need to question our role. You need to question the military. You need to question what are we using the military for.’” I echoed this in a recent post of mine calling for “disenthrallment” in order to produce good defense and foreign policy analysis.

The biggest lesson of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq is that the only real choice you have is when you enter a conflict. The filmmaker Rory Kennedy, who recently directed a new documentary on the Vietnam War entitled Last Days Vietnam, says that this was her biggest takeaway from shooting the film. Once you are engaged in a war, you ultimately will have to choose between lesser evils, because most decisions will be out of your hands. As Abraham Lincoln put it during the U.S. Civil War, “I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me.” As Clausewitz attempts to show, war has a nature of its own filled with “primordial violence, hatred and enmity” and “the play of chance and probability,” which makes it a terrible, unpredictable instrument for advancing a country’s national interest. Thus, Chuck Hagel’s remarks may be a useful incentive for self-reflection in Washington D.C.