China has moved from a focus on “great power” diplomacy – emphasizing its relationship with global powers, especially the U.S. – to prioritizing “neighborhood diplomacy” – China’s relationships with its neighbors and near neighbors. That shift, which has been slowly transforming China’s foreign policy since Xi Jinping came to power, has major ramifications for the Asia-Pacific, as well as U.S.-China relations.

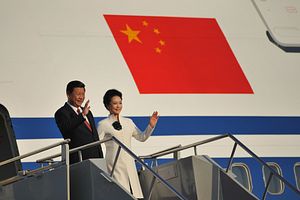

Historically, scholars have seen China as placing a premium on the U.S.-China relationship. Getting that relationship right was the “key of keys” (重中之重) for Chinese foreign policy as a whole. It’s no coincidence that Xi took a trip to the U.S. in February 2012 to prove his bona fides before assuming China’s top leadership position. And during that trip, Xi coined his first major catchphrase. Before the “Belt and Road,” before even the “China Dream,” Xi put his stamp on Chinese policy by proposing “new type of major country relations.” The phrase has dominated Chinese rhetoric on the relationship ever since. In December 2013, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi declared that China’s diplomatic priority for 2014 would be advancing “new type of major country relationships.”

How much has changed in one year. For 2015, China has instead announced that its top foreign policy priority is advancing the Silk Road Economic Belt and Maritime Silk Road (the “Belt and Road”), China’s vision for regional integration. Rather than emphasizing “great power relations,” China is focusing its energy on advancing economic, cultural, and security ties with its Asian neighbors.

The shift didn’t happen overnight. China held a major conference on peripheral diplomacy in October 2013, where Xi said strong diplomatic relations with China’s neighbors would be crucial to realizing China’s development goals. Just over a year later, at the Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs in November 2014, Xi again said that China must “promote friendship and partnership with our neighbors” as part of creating a “community of common destiny.”

The “Belt and Road” policy grew alongside this focus on neighborhood diplomacy – the concepts were introduced in fall 2013 and heavily emphasized throughout 2014. The Belt and Road, as well as the numerous smaller proposals for economic corridors (such as ones linking China-Pakistan and Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar), provide the economic underpinnings of China’s neighborhood diplomacy.

At the same time, China used regional multilateral organizations to advance its regional strategic diplomatic goals. The Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) are the two most notable examples. At CICA in particular, Xi raised the idea of a “new regional security cooperation architecture,” which in China’s definition involves a new Beijing-led security mechanism to replace the current U.S.-centered alliance structure. China’s “Asia for Asians” concept would inevitably mean that China – as the largest, wealthiest, and arguably the most powerful Asian nation – would play the dominant role in handling regional affairs.

From the “Belt and Road” to the “community of common destiny,” China is investing serious diplomatic energy in remaking its neighborhood diplomacy. The wealth of new initiatives led Chinese scholar Yan Xuetong to argue that peripheral diplomacy has replaced relations with the U.S. as the single-most important priority for Chinese foreign policy.

A recent op-ed in Xinhua cited the Chinese proverb “a near neighbor is better than a distant cousin” to explain China’s diplomatic priorities. “With proactive diplomacy reaping fruitful results, China is more actively setting the agenda for regional development,” the piece said. For China’s neighbors, this means an increased emphasis on cooperative economic projects, but also pressure to join China’s vision for regional security (and those countries with territorial disputes with China are certainly not keen on that latter point).

Meanwhile, China’s push for regional leadership puts it in conflict with the U.S., as Washington “rebalances” to Asia to shore up its own influence. At the same time, Beijing is placing relatively less of a premium on keeping the U.S.-China relationship steady at all costs (although this is undoubtedly still important). That means less of a steadying influence on U.S.-China relations at precisely the time Beijing and Washington are butting heads over regional order setting.