This week, the United States and Vietnam deepened their defense ties during a three-day trip by U.S. Defense Secretary Ashton Carter to the Southeast Asian state.

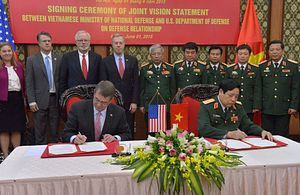

Most notably, Carter and his counterpart, Vietnamese Defense Minister Phung Quang Thanh, inked a Joint Vision Statement on Defense Relations. The statement itself, which comes as both sides celebrate the 20th anniversary of the normalization of their ties, is not wholly new. It builds on a 2011 memorandum of understanding that set out the five areas of defense cooperation: high-level dialogues; maritime security; search and rescue; humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, and peacekeeping. And the statement also clearly notes that existing mechanisms – chiefly the annual Defense Policy Dialogue (DPD) initiated in 2010 – would continue to serve as the means to review and guide the relationship.

Nonetheless, as Carter himself noted at his speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore just days earlier, the statement is important because it for the first time commits both countries to what he termed “greater operational cooperation.” While the United States and Vietnam have already been strengthening their defense relationship in areas such as coast guard cooperation over the past few years, the statement would open the door to bolder cooperation in areas like defense trade and the co-production of military equipment further down the line.

The vision statement — which is not legally-binding — was accompanied by concrete deliverables as well. For instance, Carter announced that the United States would provide $18 million to the Vietnamese Coast Guard to purchase American Metal Shark patrol vessels. This builds on existing U.S. efforts to assist Vietnam’s coast guard in the face of growing Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea, not just through providing equipment but also training and curriculum development. He also announced that the Pentagon was stationing a peacekeeping expert at the American embassy in Vietnam to help educate and guide Vietnam’s entry into global peacekeeping operations. This is in line with the understanding by both sides that the comprehensive partnership they inked in 2013 should include advancing cooperation not only bilaterally, but regionally and globally as well.

Of course, as I have noted previously, while U.S.-Vietnam relations have grown significantly over the past few years, there are still formidable challenges ahead (See: “What’s Next for US-Vietnam Relations?”). For Washington, human rights is a lingering concern, and a further easing of a U.S. lethal weapons ban is partly contingent on improvements in this area. For Hanoi, moving too quickly to embrace Washington could risk alienating neighboring China or antagonize some influential segments of the Vietnamese Communist Party who are still suspicious of the United States. And of course, Vietnam War legacy issues are still being sorted out even though both sides have come quite far in this regard.

Yet both sides have shown a determination to get past these issues over the past few years both symbolically and substantively. During Carter’s visit, he himself noted that on his stop to Haiphong, he had achieved another ‘first’ by becoming the first U.S. secretary of defense to visit a Vietnamese military base and tour a Vietnamese Coast Guard vessel. And to address the legacy of the war, he returned a diary and a belt that belonged to a Vietnamese soldier and said he hoped to see them returned to the rightful owner or his family. “With this exchange, we continue to help heal the wounds of the past. With this visit, we continue to lay the foundation for a bright future,” Carter said at a joint press conference.