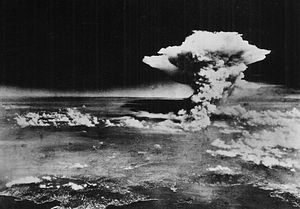

U.S. President Harry S. Truman’s decision to use nuclear weapons against the civilian populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki stands as one of the most consequential uses of weaponry in human history, a watershed moment in the twilight days of World War II, and a perennial question of moral and strategic ambiguity. In fact, all contemporary conversations about the dangers of nuclear weapons and their proliferation inevitably evoke their two uses in wartime on August 6 and August 9, 1945.

What is commonly overlooked, however—and I don’t put this forward as an attempt at revising history—is the influence the bombings themselves actually had on Japan’s decision to surrender on August 15. Indeed, the conventional understanding of the use of the bombs is that they shocked the Japanese leadership so much that they could not help but surrender in the face the awesome might of these new weapons. Those who argue in favor of Truman’s decision to use the bomb build off this to note that countless lives—Japanese and Americans—were saved by the fact that Allied forces did not proceed with Operation Downfall, the planned amphibious invasion of Japan, which in some estimates would have cost millions of lives for the Allies and tens of millions for the Japanese.

But based on what evidence we have of what Japanese leaders were writing and thinking at the time, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not a threshold event for convincing Imperial Japan to acquiesce to unconditional surrender. This is important because on a very fundamental level, the hallowed place nuclear weapons occupy in our contemporary security discourse is based on their ability to deter conflict and encourage compliance — it is assumed that these weapons work like no other. For Imperial Japan, the late spring and early summer of 1945 were already hellish. The Imperial Japanese Army suffered catastrophic losses at Iwo Jima and Okinawa; Tokyo, along with over 60 other Japanese cities, was bombed with incendiary explosives. In the case of the latter, civilian deaths were comparable to the death toll at Hiroshima and Nagasaki (the fire-bombings of Tokyo are thought to have claimed over 100,000 lives while Hiroshima and Nagasaki resulted in 120,000 and 80,000 civilian deaths respectively).

Despite the combined carnage of weeks of incendiary bombing, which reduced Japanese cities to ash, and the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan’s leaders at the time appeared undeterred. Korechika Anami, the Japanese minister of war at the time, noted that the atomic bombings were “no more menacing than the firebombing[s]” that came before them. Toroshiro Kawabe, deputy chief of staff of the Imperial Japanese Army, remarked that while the nuclear weapons caused a “serious stimulus (shock or jolt),” Japan “must be tenacious and fight on.”

Kawabe’s dairy contains another entry on August 9, 1945–the day Nagasaki was bombed–that “The Soviets have finally risen!” With the entry of the Soviet Union into the Pacific war, Japanese military leaders immediately convened to declare martial law and raised the possibility of instituting all-out military rule over Japan, supplanting the civilian leadership. In essence, for these Japanese military planners, the fact that Stalin’s Soviet Union had joined the campaign was a more significant strategic event than the bombings themselves. Even after Hiroshima had been flattened, Japanese soldiers stood prepared on the shores on Honshu, Kyushu, and Hokkaido for the impending amphibious assault. For them, the fight hadn’t ended.

The most thorough treatment of this topic–of whether the bombs actually worked in influencing Japan’s thinking at the twilight of the World War II–comes from Ward Wilson, an analyst working on nuclear weapons. Indeed, in a post for The Diplomat last year, Wilson rounds up some other evidence that our focus on Hiroshima and Nagasaki misses the mark given the broader destruction across the country. Wilson’s quantitative take on the topic last year is worth revisiting:

The United States bombed 68 cities in the summer of 1945. If you graph the number of people immediately killed in those 68 attacks, Hiroshima is not the attack that killed most. It is second, behind Tokyo, an attack using conventional bombs. If you graph the number of square miles destroyed, Hiroshima is sixth. If you graph the percentage of the city destroyed, Hiroshima is 17th. The attack on Hiroshima was not that different from other attacks. The means were different. But the ends were much the same.

As the region approaches the 70th anniversary of the war’s end in Asia in less than two weeks, it is worth recalling the historic context surrounding Truman’s decision to use the bomb. You’ll note that I’ve left out largely the broader normative question of whether bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki with nuclear weapons was the right call. That continues to be a topic of immense and impassioned contemporary debate. Indeed, for Japan, the horrors of nuclear weapons, as understood from the experiences of the survivors of those two bombings, is woven into the country’s national fabric. Yes, 70 years after Hiroshima, the world is no closer to forgetting the destructive power of nuclear weapons and renewed tensions between the United States and Russia, each with arsenals of over 7,000 warheads, will ensure that we don’t for some time. However, it’s worth recalling that nuclear weapons use against Japanese civilians in the final days of the war may not have been the turning point it’s often thought to be.