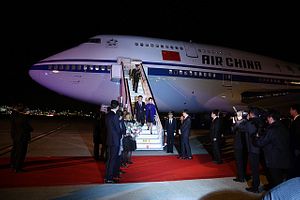

Xi Jinping was received in the U.K. with the usual honors accorded to a Head of State. Like his predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, he has slept in Buckingham Palace, enjoyed a state banquet with the Queen, and ridden in a royal carriage. There is nothing in this that proves that British politicians have decided to abandon U.K. values, condone human rights abuses in China, or ignore the impact of China’s coercive actions on the balance of security in East Asia. Perhaps what they are trying to do is to become a more credible and dependable partner for China in Europe, to work with Beijing to find a way of integrating China into the world order with minimal negative impact, or to establish common strategic priorities on important issues and parlay that into collective action.

The unfavorable comparisons between David Cameron and Angela Merkel around this visit jar. Merkel has been no less criticized for a soft approach on human rights when she meets Chinese leaders. And she has been more frequently lauded for the work she has done to make Germany China’s preferred European partner (she made her eighth extended visit to China this year). Merkel has been more adept than other European leaders at managing the relationship, but Cameron now looks like he might be catching up.

It is challenging for liberal democracies – with the U.S. as the notable exception – to engage with China without hypocrisy, now that the balance of power has shifted so far in China’s favor. Not only an economic heavyweight, but also a United Nations Security Council member, not to mention the world’s most populous country, China has become a necessary partner in achieving many diplomatic goals, such as a good outcome at the Paris climate conference, or the Iran nuclear deal. The uncomfortable image of the smaller state taking the moral high ground, talking down to Chinese politicians, while begging for trade deals has surely had its day. At least George Osborne, the assumed architect of the UK’s new uninhibited approach, seems to have a strategy: to give China more clarity and predictability; and to focus on supporting British interests, both at home and in terms of global governance and security. We can assume he would prefer to deal with a democratic China, but has recognized Britain cannot change the fact that the world’s second biggest economy is a one-Party state.

In so far as the U.K. was able to influence China’s more reprehensible behavior last year, a closer relationship with China, with more dialogue, more bilateral visits, more economic interdependence, and more two-way tourism and study, is not going to make it any more difficult to do so next year. Moreover, there is not so much in this British enthusiasm that is new. The Foreign Office decided back in 2011 to increase diplomatic resources in China, with the creation of 62 new positions in diplomatic posts there, including a new Consulate General, extra training in Mandarin for diplomats, and new programs to build links with Provinces across the country. The ambition to establish London firmly as the global center for RMB products and services outside China is a long-standing one.

At the same time, the U.K. has pursued diverse projects in the human rights arena, including putting money and effort into such areas as promotion of civil society, training judges, maintaining a human rights dialogue, held most recently in April 2015, and publishing its concerns. It’s not a zero-sum approach: The larger and better resourced European Union member states talk more to China about trade and investment, and more about human rights, cyber security and other issues than the smaller countries can possible manage in any of those areas. David Cameron’s 2012 meeting with the Dalai Lama was not a statement of a new policy, neither in the way it was conceived, nor how it was resolved. Like other sitting prime ministers, he’s seen him once, seeing off a domestic constituency. He’s ridden out the storm, which was worse than he had anticipated (though it didn’t slow down historically high growth in U.K. exports to China). And it’s very unlikely he’ll ever see him again.

Regarding nuclear power plants and other investments, China has already made successful investments in critical infrastructure in Europe, such as the Piraeus Port in Greece. British ministers clearly doubt that China’s intention in investing in nuclear power in Britain is to create vulnerabilities that they can exploit during future hostilities, and believe they are taking sufficient security precautions. The Chinese state’s influence beyond its borders is bound to increase through this kind of investment, and through strategies such as One Belt, One Road. But as the U.K. is the leading destination for foreign direct investment in Europe generally, there should be no surprise that it has stepped up first to welcome the new big investor on the block.

Whether China will be able to influence the UK’s behavior on issues of importance is still unclear. Let us refrain from assuming only bad can come from a good relationship between the U.K. and China and wait for some evidence.

Rebecca Fabrizi is Associate Director of the Australian Centre on China in the World at the ANU. She was formerly head of China policy in the European External Action Service and a British Diplomat before that. Her research focuses on EU-China and China-Russia relations.