Chinese President Xi Jinping wraps up his visit to the U.K. today with a stopover in Manchester. He had a productive time in London, where the U.K. and China signed deals on a nuclear power station (Chinese companies will hold a roughly one-third stake in the Hinkley Point C nuclear power plant), cruise ships (Carnival will sell roughly $4 billion worth of ship to China), and jet engines (Rolls Royce won a $2.2 billion contract to design new jet engines). All told, China and the U.K. sealed over $40 billion worth of deals.

The scale of the deals is not so unusual – after all, when Xi was in the U.S., Chinese companies promised to buy aircraft worth $38 billion in a single deal with Boeing. From a political standpoint, what’s more interesting in the high-level (and explicit) commitment Britain has made to be China’s top partner in the West.

“I’m clear that the U.K. is China’s best partner in the west,” David Cameron said this week, repeating what seems to have become his government’s mantra.

Xi, however, put a slightly different spin on the formula, calling on the U.K. “to fulfill its aspiration to become China’s strongest advocate in the west.” There’s a big difference between “partner” and “advocate” – the latter implies a far more active role for London taking up China’s cause in its relationship with the EU and likely the U.S. as well.

On the economic front, that means London fulfilling earlier indications that it would help drive forward negotiations on a China-EU Free Trade Agreement, even as other parties in the EU remain hesitant. “Both sides support the early conclusion of an ambitious and comprehensive China-EU Investment Agreement, and call for the swift launch of joint feasibility study for a China-EU Free Trade Agreement,” the joint statement issued during Xi’s visit said.

However, the idea of the U.K. and “China’s strongest advocate” could extend beyond economics. In the joint declaration, the two sides committed to building a “global comprehensive strategic partnership.” The statement said that Xi’s visit “opens a golden era in China-U.K. relations featuring enduring, inclusive, and win-win cooperation.”

Tellingly, that partnership is described in language straight out of the Chinese foreign policy handbook: “The two sides will further enhance political trust based on equality and mutual respect, and in that spirit recognize the importance each side attaches to its own political system, development path, core interests and major concerns.” Acceptance of China’s formula of “mutual respect” is generally considered to require accepting China’s “core interests” (which in some formulations includes Beijing’s claims in the South China Sea) while refraining from “preaching” on human rights issues.

London has already started on the human rights front– it reportedly arrested and searched the homes of three people who protested China’s human rights violation near Xi’s motorcade. One was a Tiananmen Square survivor; the other two were Tibetans. “It feels like it was when I was in China,” one of the arrested protesters told The Guardian.

Meanwhile, London and Beijing are making tentative steps to expand their partnership on security issues. China and the U.K. agreed “to establish a high-level security dialogue to strengthen exchanges and cooperation on security issues such as non-proliferation, organized crime, cyber crime and illegal immigration.” Two other points in the joint statement saw the two sides agree “to strengthen cooperation on settling international and regional disputes peacefully” and to “increase multilateral cooperation to help resolve conflict through diplomatic and political means to achieve stability.”

“Our relationship goes beyond trade and investment,” British Prime Minister David Cameron said in a press conference with Xi. “China and Britain are both global powers with a global outlook.”

London’s shift toward China comes even as its traditional ally, the United States, is growing increasingly concerned over Beijing’s actions in cyberspace and the Asia Pacific region. In this light, the U.K.’s role as China’s “advocate” puts it at odds with the rest of the West — and could undermine diplomatic efforts by other EU countries and the United States. As Aaron Friedberg, professor of Politics and International Affairs at Princeton University, told Time, “When the Chinese are behaving badly in a number of different domains—cyber, cracking down on dissent, tightening control of Internet— there is much less chance of convincing them that they need to moderate their policies if countries like Britain are chasing after them.”

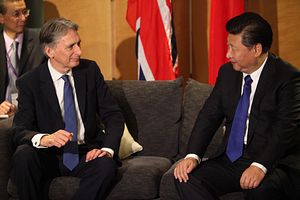

British Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond rejected the idea that the U.K. would compromise its own national interests in pursuit of Chinese investment. “National security depends on economic security,” he said in an interview with the BBC. Cameron himself argued during the press conference with Xi that “the stronger our economic trading, business and other partnerships, the stronger our relationship and the more able we are to have the necessary and frank discussions about other issues” such as human rights.

The more interesting question, however, is how London will approach not Chinese domestic policies, but its security and foreign policy approach — particularly in areas where the United States is a vocal critic of China’s actions. Will London, as China’s “best partner in the West,” balk in the future at allowing the G7 countries to repeat their expression of concern this year on the East and South China Seas? In other words, will the U.K. start to play the role of pro-China spoiler, just as Cambodia tends to do in ASEAN meetings?

Meanwhile, as an interesting side effect of Britain’s new China approach, China seems to have upgraded its assessment of London’s global importance. In 2013, when China-U.K. relations were still rocky, China’s Global Times dismissed London as a has-been: “[T]he U.K. is not a big power in the eyes of the Chinese. It is just an old European country apt for travel and study.” Now that Beijing expects London to go to bat on the CCP’s behalf, thought, the U.K. has been upgraded to a “major” country “with significant influence,” as Xi put it in his press conference remarks. After all, what’s the point of winning an “old European country” as an advocate?