Chinese President Xi Jinping was in Antalya, Turkey November 15 and 16 for the G20 summit, a meeting of the world’s major economies. This year, the usual economic focus of the summit was derailed by the terrorist attacks in Paris on November 13, which suddenly placed the fight against terrorism at the top of the agenda. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, writing for Project Syndicate just after the Paris attacks, said that “terror will now vault to the top of the long list of pressing issues that will be discussed” at the G20 summit.

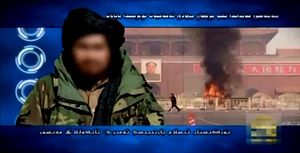

For China, terrorism domestically is tantamount to one group: the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), which seeks to create a separate country (East Turkestan) out of Xinjiang province. Though details on the group are hazy, China blamed separatists for the spate of terrorist attacks that rocked the country in late 2013 and 2014: a deadly, intentional car crash into Tiananmen Square in Beijing, a bloody attack by knife-wielding assailants at the Kunming railway station, and two separate bomb attacks at the Urumqi railway station and a popular market in Urumqi. Though Chinese officials and media are careful not to make the link explicitly, Xinjiang separatists are usually members of the Uyghur ethnic minority group.

Given the ethnic dimension, some outside observers remain unconvinced that ETIM exists as a coherent organization and have accused China of using ETIM as a front for violating Uyghur rights. Alim Seytoff, president of the Uyghur American Association, told The Diplomat in 2013 that China labels “every instance of alleged violence involving Uyghurs the work of ETIM in order to justify its brutal suppression of the Uyghur people’s legitimate demands for human rights, democracy and freedom.”

Given these concerns, Beijing has had trouble getting counter-terrorism against ETIM or other separatist groups included in the broader international fight against terrorism. That’s something China would like to change, and it showed in Beijing’s response to the tragedy in Paris.

On November 16, in the first regular press conference after the Paris attacks, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hong Lei called terrorism “a common challenge faced by all humanity” and urged “joint efforts … to address both the symptoms and the root causes of terrorism. Hong added that “double standards should be abandoned,” a reference to China’s displeasure when the West is slow to call violent attacks in China terrorist actions.

Part of the world’s “joint efforts” to combat terrorism, Hong said, should involve targeting Uyghur separatists. “Clamping down on the ETIM should be an integral part of the global fight against terrorism,” Hong argued, saying ETIM “posed grave security threats not only to China but also to the international community.”

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi made similar comments on the sidelines of the G20 summit on Monday. “China is also a victim of terrorism, and cracking down on ETIM should become an important part of the international fight against terrorism,” Wang said. Xi himself spoke out against “double standards” on terrorism as well.

China’s concerns were represented in the G20 statement on the fight against terrorism, which reaffirmed “our solidarity and resolve in the fight against terrorism in all its forms and wherever it occurs.” The statement added, “We unequivocally condemn all acts, methods and practices of terrorism, which cannot be justified under any circumstances, regardless of their motivation, in all their forms and manifestations, wherever and by whomsoever committed.”

Ironically, however, Turkey is one of the countries where it is most difficult for China to gain support in its fight against ETIM and Xinjiang-based terrorism. Turkey has a sizable Uyghur population, and is often the preferred destination for Uyghurs trying to leave Xinjiang for a life abroad – whether legally or not. Earlier this year, Reuters reported that Turkish diplomats in Southeast Asia may have been helping Uyghurs by providing them with necessary travel documents.

Turkish sympathy for Uyghurs boiled over into ugly anti-China riots earlier this year, fanned by reports that China was restricting religious observations of Ramadan in Xinjiang and by Thailand’s decision to deport nearly 100 Uyghurs back to China. The tensions cast a shadow over Erdogan’s trip to Beijing in July of this year.

Despite those tensions, when Xi met with Erdogan on the sidelines of the G20 summit, the two sides agreed to strengthen their cooperation on fighting terrorism and people smuggling. China has expressed concerns that Uyghurs leaving China through unofficial channels may be seeking to join Islamic State, the group that claimed responsibility for the Paris attacks. Critics, however, say Uyghurs emigrants are more properly dubbed refugees, who are fleeing oppression in their homeland. Turkey has generally held to the latter interpretation, much to China’s chagrin.