The Trans-Caspian transport route is many things to the many states involved. Transporting goods from Europe to China and back–at the moment crossing through Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan (as well as both the Black and Caspian Seas)–is an alternative to the Russian route. The clearest rationale behind the recent focus on the route is political, but that’s not the only motivation for the states involved. The trans-Caspian route satisfies several checkboxes: it not only avoids Russia, but it can potentially capitalize on the opening of Iran, and in the end, increased trade options please China.

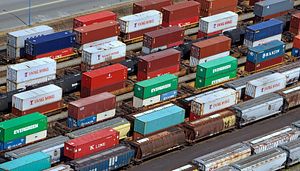

Avoiding Russia, as I noted in January, is the prime rationale for reinvigorated focus on the trans-Caspian route for Ukraine. And given Russia’s decision to block easy transport of goods from Ukraine to Kazakhstan via its territory, Astana too seeks to avoid the Russian complication. Why push to go through Russia when you can go around? According to the Astana Times, the first test shipment, which departed from Ukraine on January 15, arrived at its destination in China on February 2. The shipment launched via ferry from the Ukrainian port in Chornomorsk (until very recently called Ilyichevsk) and crossed the Black Sea to Batumi, Georgia where it continued on rail through Georgia and into Azerbaijan. At the new Azeri port at Alyat, about 65 kilometers south of Baku, the cargo was loaded onto a second ferry and sailed for the Kazakh port at Aktau where it once again took to the rails headed for the Chinese border.

According to the Astana Times, the Ukrainian Minister of Infrastructure, Andrey Pivovarsky, said the parties involved will likely meet in Baku toward the end of February “to sign the final protocol to coordinate all technical problems and minor uncertainties, so that I expect the start of regular transportation already in March this year.”

The trans-Caspian route has expansion potential as well. The lifting of sanctions on Iran in connection with last year’s landmark nuclear deal unshackles a major regional player. Iran’s connections with the Caspian littoral states have been subdued under the weight of sanctions. However, that has not harmed state to state relations per se; nor does it change the enormous cultural influence Iran has had historically on Central Asia.

But most importantly, Iran has what Central Asia lacks: sea access. The port of Chabahar–the development of which, notably, is being backed by India–will link into the trans-Iranian railway system which connects to a port on the Caspian. Iran therefore has huge potential as an outlet for Central Asian goods into the world market and a input for Chinese goods to both Central Asia and Europe.

For China, the trans-Caspian transport network is a piece of the larger One Belt, One Road initiative aimed at resurrecting the ancient Silk Road. Ukrainian ministers are absolutely bullish on its potential and Chinese officials are supportive. TASS reported in late January that the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman, Hua Chunying, said “As for the proposal by the Ukrainian side and some other countries on laying a new transport route, China also supports it.”

But Xinhua, on the occasion of the first test train’s arrival, injected a degree of caution noting that there remain two major problems with the trans-Caspian route. The first is cost: shipping a 40-foot container by train (and ferry) costs about $8,900, according to Ukraine’s State Railway Service. Transport entirely by sea is about 30 percent lower.

The second is time. Transferring cargo from ferry to train to ferry to train is time-consuming and contingent on both ferry and train service which is not frequent enough to be cost-effective and which may be adversely impacted by weather. At present, the Ukraine-Georgia ferry runs twice a week. These problems can be moderated to a degree, but only if there’s the political motivation to do so. For those predicting increased competition between Russia and China, this will be one road to watch.