Tajik border authorities say they thwarted a group of nine militants attempting to illegally cross the Tajik-Afghan border near the Panj border crossing, north of Kunduz. A Tajik border guard and one of the armed Afghans were killed in the operation and several were arrested.

According to a statement from the Tajik border authorities, “A clash between a border patrol and a nine-strong group, which was armed to their teeth and had crossed over from Afghanistan, took place near the Panj border post.” Per AFP, the statement referred to the Afghans both as a “terrorist group” and “smugglers.” While both could be true, the Afghan and Tajik authorities are clearly stressing the first association, while the latter is a likely dimension.

Both Asia-Plus and RFE/RL cite Afghan officials as saying that the group were members of the Taliban. Militant activity has increased in Afghanistan’s northern provinces in the past year. For 15 days in October 2015, Taliban seized control of Kunduz. Although Afghan forces regained control of the city, the province remains restive in parts. Afghan officials say the Taliban control 30 percent of Imam Sahib district, the area of Kunduz province bordering Tajikistan.

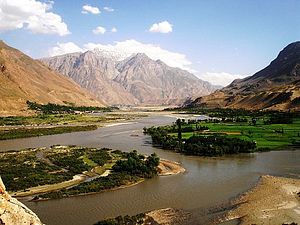

In the Panj river, which defines the border, there are several small islands that smugglers routinely use to cross over. Tajik forces were clearing the islands over the weekend. Last year Tajik border forces skirmished with Afghan smugglers at least 30 times, killing 16.

A 2006 article in the Chicago Tribune referred to the Panj river as a “drug smuggler’s dream.” That remains true a decade later. Neither the Tajik nor Afghan accounts of the weekend skirmish mention drugs, but it’s reasonable to suggest that the nine-man group were some of the many drug traffickers who routinely cross the border rather than terrorists infiltrating Tajikistan for some unknown reason.

Despite more than $7 billion directed at opium poppy eradication in Afghanistan over more than a decade and more spent on border security programs and counternarcotics initiatives on both sides of the river, drug smuggling continues relatively unabated. The U.S. State Department’s 2016 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report says that Tajikistan is “located on one of the highest volume illicit drug trafficking routes in the world.” The 2014 report, citing the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), claimed that 85 percent of the heroin and opium smuggled through Central Asia traveled through Tajikistan and that the Tajik authorities seized “ just over one percent of the opiates trafficked through the country in 2013.”

Included in the U.S. State Department’s FY2016 budget request is $7.8 million for counterterrorism and border security assistance in Central Asia and a further $5.4 million for counternarcotics and transnational crime. Although security assistance requests for Central Asia have fallen in recent years–declining 26 percent between 2015 and 2016’s request of $24.7 million–the budget is still three times larger than pre-9/11 levels. In FY2000 security assistance for the entire region rested at $7.9 million. Other entities, such as the EU, OSCE, SCO, and Russia, have spent millions more on the same types of initiatives: border security and counternarcotics. The results of those investments seem negligible.

State’s annual International Narcotics Control Strategy Report only pays lip service to the issue of corruption within Tajik agencies, and its impact on foiling progress in combatting the drug trae. The small section on corruption begins with this early contender for obvious statement of the year, “As a matter of policy, the government of Tajikistan does not encourage or facilitate illegal activity associated with drug trafficking.” It’s followed by more useful comments, pointing to low salaries, the massive scale of profits available in the drug trade and lack of other (legal) profitable endeavors as motivation for corrupt officials. Unsaid is the link many regional analysts suggest exists between major drug smugglers and Tajikistan’s leadership. The 2014 report has similar language but also adds this important note: “Arrests and prosecutions of major traffickers remained few, and those that did take place were presumed to target small independent operators rather than major traffickers.”

The latest incident–like previous skirmishes and semi-routine drug busts–just scratches the surface of a deeply ingrained problem.