China’s 13th Five-Year Plan for energy (Energy 13FYP) might be one of the most anticipated official documents in the world and is one that will have far-reaching impacts on the carbon trajectory of the world’s number one emitter. Recently, information about the plan begins to surface in the Chinese media.

On July 11, the Economic Information Daily, a major financial newspaper, reported that publication of the central government policy intently watched by the climate and energy community is “imminent.” More specifically, the report spells out key targets that are being considered by the country’s energy policymakers.

This blog intends to summarise the information about those targets based on publicly-available information. Before that, a bit of background.

What’s up with all the FYPs?

The first question anyone new to China’s planning cycles may ask is: What’s the nature or status of this Energy 13FYP? Our readers may remember that in March, China unveiled its 13th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development (2016-2020), which contains a set of climate and energy related targets, including an energy consumption cap and a 15 percent goal for the share of non fossil-based energy in the country’s primary energy mix. If we consider this the “Master Plan” for all aspects of China’s development in the next five year period, the Energy 13FYP is a specification of that Master Plan for the energy sector, with more detailed targets that will better guide policymaking, government spending and project planning in the sector.

The chart below illustrates the hierarchy of Chinese plan making, which locates the Energy 13FYP as a “Special Plan” for a specific sector. Special planning follows the completion of national general plans, and its process is less predictable. It is noteworthy that for the 12th Five Year Plan cycle (2011-2015), the Energy plan took almost two years to make and was only released in 2013. Therefore, even if media declare the Energy 13FYP “imminent,” there is no guarantee when exactly it will be published.

What can we expect from the Energy 13FYP?

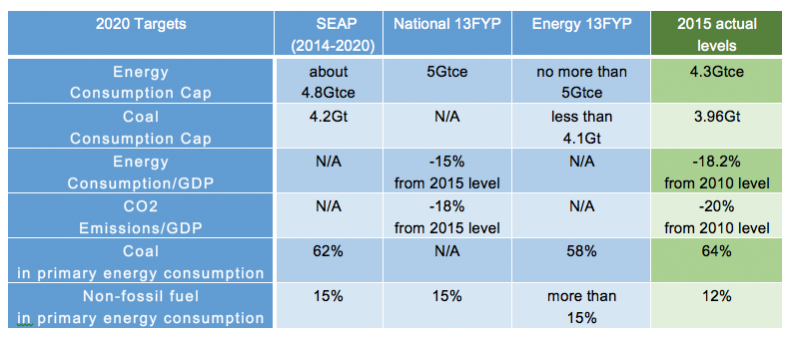

The chart below illustrates the numerous 2020 targets already declared by the Chinese government through its Strategic Energy Action Plan (2014-2020) and its national 13th Five Year Plan. They are set against actual levels at the end of 2015 as a benchmark. The comparison serves as a basis to gauge if the Energy 13FYP is sufficiently ambitious to meet China’s domestic and international commitments.

It should be noted that what is currently known about the targets in the Energy 13FYP is based on media reports and publicly available information. It is subject to change depending on ongoing internal consultation and negotiations among policy makers.

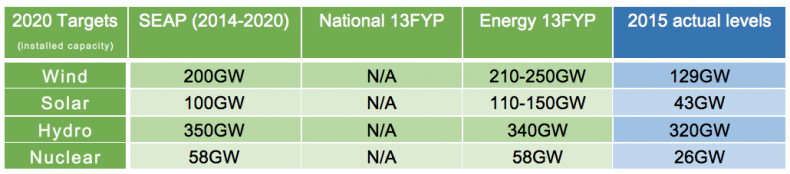

From this comparison, it is clear that most of the targets in the Energy 13FYP will not be entirely “new.” Many of them are well in line with existing thinking embodied in previously announced policy items, in particular the Strategic Energy Action Plan (2014-2020), which, at the time of its publication, was already considered ambitious in curbing coal consumption and CO2 emissions beyond international expectations. Yet it is still noteworthy that policy makers seem to be even more determined to squeeze coal’s share in the country’s energy mix, lowering its 2020 percentage in primary energy consumption from 62 percent to 58 percent, and capping its consumption at 4.1 Gt (which means roughly at 2014 levels).

The country is also aiming higher for its renewable energy sector, even though different information sources differ on the scale of upward adjustment. In June 2016, a deputy administrator of the National Energy Administration (NEA) indicated that wind and solar installed capacity should reach 210 GW and 110 GW respectively by 2020, higher than what was declared at the end of 2014. Those numbers seem to have grown even further to 250 GW and 150 GW in the most recent information released by the Economic Reference.

Between the lines

Media reports about the Energy 13FYP also reveal deeply rooted concerns that have troubled Chinese policymakers:

1. Overcapacity: China’s power sector is faced with a severe overcapacity problem. Slowing demand for electricity due to the economic downturn and slashing of energy intensive industries has caused widespread under-utilization of existing power generation capacities, which are seeing their lowest utilization hours since 1978. Yet the country is still seeing fast build-up of coal-fired power capacities as a result of inertia (many projects were approved in the heyday of the economic boom) and perverse incentives (dropping coal price and a government fixed electricity tariff is increasing the profit margin for coal power). The worsening overcapacity situation has prompted regulators to consider putting a two-year “freeze period” in the Energy 13FYP for the approval of any new coal-fired power projects.

2. Curtailment: The other side of the overcapacity coin is curtailment of renewable energy, particularly wind and solar energy in western parts of the country. A combination of transmission bottlenecks and market set-up has blocked large chunks of renewable electricity from reaching the grid. In 2015, 15 percent of China’s wind energy was wasted, a historical high. Based on what’s written about the Energy 13FYP, the problem seems to have pressed policymakers to put more emphasis on reining in curtailment, at least for the first half of the 13th Five Year cycle, as opposed to further expansion of installed capacity. Whether this will become a factor that contributes to lower-than-expected wind and solar targets remains to be seen.

Ma Tianjie is chinadialogue managing editor in Beijing. Before joining China Dialogue, he was Greenpeace’s Program Director for Mainland China.

This post was originally published by chinadialogue and appears with kind permission.