Looking at some of the sensationalist headlines and commentary coming out of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s China visit this week, one might think that the Philippines is engaged in nothing short of a 180-degree turnaround in its foreign policy where it is set to abandon its decades-old treaty alliance with Washington to embrace Beijing after years of bearing the brunt of its South China Sea assertiveness.

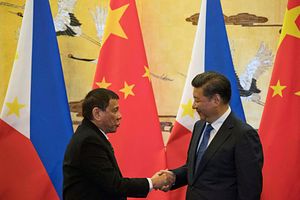

After a nearly 30-minute rant at a Chinese-Philippine Trade and Investment Forum at the Great Hall of the People on October 20, Duterte announced a “separation” from the United States in a statement that sparked a media frenzy. And during his time in Beijing, the Philippine president and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping witnessed the signing of no less than 13 bilateral cooperation documents, with Duterte meeting a total of four of the seven members of the Chinese Communist Party’s powerful Politburo Standing Committee. Officials from both sides emphasize that this is just the beginning and more impressive deliverables could soon follow.

Yet a close reading of these developments in broader perspective, along with discussions with aides close to Duterte and with observers and policymakers in Beijing and Washington, D.C., over the past two weeks, indicates that this shift is much less dramatic and far more complex than it is being made out to be, at least thus far.

Historical Perspective

Duterte’s embrace of China is not as new or unexpected as some suggest. He is, in fact, just the latest in a line of Philippine leaders who has tried to balance relations with the United States and China in addition to other partners with varying degrees of success during the three decades that have elapsed since the end of the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos in 1986.

Fidel Ramos, who dealt with the last wave of China’s South China Sea assertiveness in the 1990s (and was initially tapped to serve as Duterte’s special envoy to Beijing), sought to engage Beijing in talks, but also secured a Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) with the United States, recognizing that American hard power was necessary to at least slow down the pace of China’s “creeping assertiveness.” Thereafter, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo sought to deepen the Philippines’ hedging position vis-à-vis Washington and Beijing, but ultimately ended up going too far in her engagement with Beijing (See: “The Risks of Duterte’s China and South China Sea Policy”).

Duterte’s predecessor, Benigno Aquino III, moved Manila much closer to the United States, in large part due to China’s growing assertiveness in the South China Sea. Though there were attempts later on by the Aquino administration to move towards repairing ties with China, the filing of a South China Sea case had so poisoned the relationship that few in Beijing saw good prospects for better Sino-Philippine ties until a new president took office. Duterte is now trying to move the dial back towards Beijing, a shift that was ultimately bound to happen irrespective of who Aquino’s successor would be, but is also far from assured.

Arroyo’s experience is a good demonstration of the limits of any warming of Sino-Philippine relations. For those blown away by the 13 pacts Duterte inked with Xi, it is worth noting that Arroyo signed no less than 65 agreements with China during her presidency. But that cooperation was eventually sullied by a controversial joint development deal in the South China Sea inimical to Manila’s interests that was cut with Beijing in exchange for Chinese-backed infrastructure projects, which ended up being embroiled in one of the largest corruption scandals in Philippine history.

Of course, these shifts have also taken place amid a vast asymmetry in favor of the U.S.-Philippine alliance across the security, economic, and people-to-people realms (See: “The US-Philippine Alliance Under Duterte: A Path to Recalibration“). In terms of security, the Philippines has been part of the original U.S. hub-and-spoke alliance network formed in the post-WWII period for over six decades, with the Mutual Defense Treaty signed back in 1951. Though defense ties have had their ups and downs, progress during the Aquino years, with the signing of the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) and Manila’s central role in measures like the Southeast Asia Maritime Security Initiative (MSI), it has become a key part of the U.S. rebalance to the Asia-Pacific (See: “Why the Philippines is Critical to the US Rebalance to Asia“).

Economically, though China may be the Philippines’ largest trading partner, the United States is its biggest foreign direct investor; second major source of official development assistance (ODA); and key source and conduit for remittances for Philippine workers, which still contributes around one tenth of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). Socioculturally, strong people-to-people linkages date back even further to the U.S. colonial legacy in the first half of the twentieth century and today Filipino-Americans, who number over four million, make up the second-largest Asian-American diaspora group in the United States.

The close bonds between the United States and the Philippines is a notion widely appreciated within much of the Philippine bureaucracy and wider elite, which is in part why many are already pushing back against Duterte’s drift away from Washington. The Filipino people also consistently have a highly favorable view of the United States and a very unfavorable one of China, with some minor shifts in the data over the years (See: “The Truth About Duterte’s Popularity in the Philippines”). One recent poll by the respected Social Weather Station (SWS) survey, released just ahead of Duterte’s China visit, indicated that in terms of net trust rating – the difference between the percentage of Filipinos who distrust vs. trust a certain country – the United States was at +66 while China was at a dismal -33.

A Still-Evolving Foreign Policy

Apart from this historical perspective, Duterte’s attempt at a U.S.-China rebalance also needs to be placed in the broader current context of a still-evolving foreign policy. We are just more than three months into the six-year term of a domestic-focused president who has little foreign policy experience, but has signaled quite a lot of foreign policy change without much specifics about how that would take place.

Duterte and other administration officials have talked about his China embrace as part of an “independent foreign policy,” which means (at least rhetorically) relatively less dependence on the United States and more diversification with other players including Beijing. But we do not yet know how Duterte’s initial approaches to the United States and China will end up actually playing out when it comes to concrete policy and how these two countries will fit into his broader foreign policy vision (See: “The Trouble with the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte“).

Figuring out how Duterte’s attitude towards the United States will eventually play out is especially difficult. His decision to move more towards China and away from the United States is not based purely on pragmatism, as some have suggested, but also a mix of other factors including his own historical experiences and personal leanings. And though he does have a deep-seated dislike and distrust of the United States, which some of his close aides confirm, it is not clear how flexible that position is when it comes to eventually cooperating with Washington. His expletive-laden and hyperbolic statements make for good headlines, but tell us little about his actual views. Duterte himself has admitted that they represented expressions of frustration to get people to listen rather than policy pronouncements to be translated into action, something his spokesperson Ernesto Abella has also told media outlets.

On the one hand, it is clear that Duterte’s experiences with the United States have led to a fierce anti-American sentiment built up over decades. The mix of factors that comprise his anti-Americanism include his leftist orientation, grievances about the U.S. colonial legacy in the Philippines, as well as a string of personal incidents, including what he believes was the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) involvement in helping an American escape charges for an explosion that occurred in Davao City back in 2002, when he was mayor – the so-called Meiring Incident.

Duterte was already publicly stating his opposition to aspects of U.S.-Philippine security cooperation during his time as mayor, including the Balikatan exercises being held in the Davao Gulf and the United States wanting to use an airport for drone surveillance. And in October 2015, before he even confirmed that he was running for president, he offered a preview of his foreign policy in an interview with Philippine media outlet Rappler, saying that the Philippines would be “better off” if it made friends with China.

Duterte’s deep dislike of the United States was on full display during his speech at the Forum, which came almost exactly a year after that Rappler interview. Though the media fixated on the soundbite about his “separation” from the United States, what was really shocking about his speech at the Forum – even, The Diplomat understands, to some members of the audience at the Great Hall of the People – was that he spent much of his half-hour address laying out a Manichean worldview comprising of America on the one hand and “Orientals” on the other, going into the reasons why he disliked the United States from experiences with immigration officials to the way they speak.

But part of Duterte’s frustration with the United States is also specific to this administration. In an interview with Al Jazeera on October 16 just before his trip to China – his first exclusive interview since taking office – he said his anger was also tied to a series of incidents since taking office, including misinterpretations of his insults, criticism of his ongoing war on drugs, as well as perceived threats to cut assistance. These specific incidents only strengthen his belief that Beijing rather than Washington is the better partner for Manila.

Though addressing Duterte’s deep-seated distrust and dislike of the United States may be difficult, it remains to be seen whether smoothing over the differences between the two countries is possible. On the one hand, with new ambassadors on both sides, a fresh administration in the United States in January, and the next U.S. president expected to visit the Philippines next year when it chairs ASEAN, the opportunity is there if there is the willingness to use it.

Then again, after arriving in the airport in Davao City after his China trip, Duterte told reporters he would not go to the United States “in this lifetime,” and would even find a way not to fly through the United States when he has to attend the upcoming Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit meeting in Peru.

“It’s difficult because for him it’s policy, personal, historical, ideological, et cetera, combined,” an aide close to Duterte told The Diplomat on Saturday after his visit to China.

“So that’s why I say we need to see how much adjustment room is there and it takes time,” the aide, who declined to be identified so he could speak freely about the nature of the president’s views, added.

It is also still unclear how both the United States and China fit into Duterte’s broader foreign policy vision. Some of this, some diplomats say, will become clearer once Duterte engages not just China and the United States, but other important countries as well like Japan (which he visits this week) as well as others when it chairs ASEAN next year (See: “Japan-Philippines Relations Under Duterte: Full Steam Ahead?“). In some of his rhetoric, including the Forum speech in Beijing, one can detect a bit of an “Asia for Asians” bent, with rhetoric directed against the West and an affinity for Asian countries like China, Japan, and South Korea.

And in response to Duterte’s “separation” from the United States comment, Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III and National Economic and Development Agency Director General Ernesto Pernia also issued a statement clarifying that the focus of the Cabinet would be to “move strongly and swiftly towards regional economic integration,” which is why the government has prioritized foreign trips to ASEAN and the Asia-Pacific. If this is indeed part of the vision that centers on wider Asian economic integration, it would imply engaging more not just with China, but other major Asian economies as well.

Policy Continuity and Change

One also needs to be cautious about the extent to which Philippine policy towards the United States and China is actually changing beyond the headlines and even Duterte’s own rhetoric. Take, for instance, Duterte’s claim to sever military ties with the United States. His most serious statements have been those suggesting an ending of bilateral exercises, the ending of the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) signed in 2014, and even revisions to the Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT).

But when Philippine Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana was asked during his Senate confirmation hearing this week whether the government would move ahead with any of these declarations, he responded by saying that Duterte had been issuing statements without consulting his cabinet. Everything in the U.S.-Philippine defense relationship is currently running as planned, Lorenzana added. However, he also added that he would be presenting findings on these various aspects of U.S.-Philippine security cooperation during a cabinet meeting in early November, since Duterte said he would need inputs from the cabinet to make a decision on them.

“As of now, there is no decision to suspend training next year, the VFA is still on, everything is going, sir,” Lorenzana said.

One Philippine defense official told The Diplomat that he was “uncertain” whether Duterte “understood the full value” of the exercises held between the two countries each year, which total 28 and extend beyond just traditional security but also other key areas like humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.

As Duterte’s own advisers and spokesperson have often said, we should pay more attention to any policy actions that are concretized and followed through on rather than just rhetoric.

Similar caution is warranted in the case of the Sino-Philippine relationship. The 13 bilateral cooperation documents, which cover a wide range of economic and security fields – including trade and investment, industrial capacity, agriculture, media, tourism, drug control, and even coast guard collaboration – are no doubt an impressive list of deliverables.

But if you look at the documents listed, most of them (eight) are memorandums of understanding (MOUs), which are not binding commitments and look less developed than some of the others, like an implementation program of the MOU on tourism cooperation, a memorandum of agreement on news and information exchange, or an action plan on agricultural cooperation. Scrutinizing the nature and of these documents is important because anyone familiar with China’s economic ties with Southeast Asian states has become used to the reality of initial pledges not being realized.

To be sure, these documents may indicate only the beginning of a set of more concrete, binding agreements that are even more significant. But given the fact that we know very little about the exact content of these agreements, it is difficult to assess how significant they are. We may know more in the coming weeks, however, after which we may be able to make a better assessment either way. Some Philippine lawmakers are already supporting a resolution calling on senate committees to conduct an inquiry into the overall foreign policy direction of the government, including learning more about what exactly the terms of the 13 agreements are.

Future Scenarios

Ultimately, the fact is that while there has been a lot of brouhaha around Duterte’s approach towards the United States and China, it is still early days and we will have to see how things evolve for the rest of his six-year term.

One scenario would see Duterte acting on the zero-sum premise that better relations with China must necessarily come at the expense of close ties with the United States, eventually resulting in a downgrading of ties with Washington as Manila continues to move much closer to Beijing. Since Duterte already sees little value in U.S.-Philippine security cooperation and its various components, one cannot dismiss the possibility that he, in spite of opposition from some of his cabinet, will move to downgrade that if Beijing is willing to meet his price.

That said, even if he attempts to do so, Duterte’s pragmatism, the wisdom of his advisers, and the institutional constraints of the presidency probably means that downgrading will be selective, perhaps targeting certain exercises that Beijing finds most problematic or even not having them in the South China Sea.

Such a scenario would create a downward spiral that could affect the U.S.-Philippine relationship more severely, and perhaps provide even more opportunities for Beijing and Manila to cooperate. If Duterte continues spewing anti-U.S. rhetoric, exacerbating human rights concerns, and moving towards severing elements of bilateral cooperation, it will be very difficult for supporters of the alliance to prevent critics in the U.S. Congress and elsewhere from taking punitive actions like funding cuts or reacting with rhetoric that would spark a war of words that benefits neither side. As it is, Duterte’s “separation” statement has already resulted in a publicly tougher response from both the U.S. State Department as well as the U.S. embassy in Manila that we had not seen previously.

But on the other hand, given the recent history of Sino-Philippine relations, one cannot discount the possibility of an alternate scenario where Manila’s ongoing rapprochement with Beijing could be halted or at least slowed considerably by number of factors, leading Duterte to moderate his approach towards Washington. History has demonstrated that as more channels open in Sino-Philippine relations, including among business networks as well as think tanks and other institutions, managing the complexity of coordinating various channels and avoiding capture by specific interest groups is even harder, and this can give rise to everything from corrupt deals to conspiracy theories around certain big businesses (See: “China and the Philippines Under Duterte: Look Beyond a Voyage“). If this ends up playing out, that could see Duterte move a little closer to the United States having not been able to get as much diversification as he initially desired.

This caution is shared by more seasoned observers of the Sino-Philippine relations in Beijing. During a conversation last week on the sidelines of the Xiangshan Forum, one Chinese interlocutor familiar with the planning of Duterte’s China visit told The Diplomat that Duterte’s treatment of the United States, along with the rocky history of Beijing’s ties with Manila, suggested that caution was in order in case bumps were ahead.

“If this is how he treats old allies, how will he treat new friends?” the interlocutor, who did not want to be identified, said. “He [Duterte] is bold, but also at the same time unpredictable.”

Another scenario would see the gradual improvement in U.S.-Philippine relations take shape alongside the more dramatic shift towards China, thereby preserving more balance in Manila’s alignments with respect to Beijing and Washington. With new ambassadors on both sides, a fresh administration in January, and the next U.S. president expected to visit the Philippines next year when it chairs ASEAN, the two countries have an opportunity to craft a framework for at least selective cooperation in certain areas if they so desire. Adjusting to shifting alignments is not new to the United States or even the Obama administration, as the management of the U.S.-Thai relationship demonstrates (See: “Managing the Strained US-Thailand Alliance“).

Getting there, however, will not be easy. The United States would need to convince Duterte that it can play a greater role in the advancement of some his administration’s priorities that are in the national interest in spite of his own personal biases against Washington. Given the state of the relationship now, simply advertising the good work that already goes on in the alliance – including drug seizures that have occurred at the Ninoy Aquino International Airport with the help of the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) – will be insufficient.

Washington no doubt recognizes this, and its most senior Asia diplomat Daniel Russel is already in Manila where he will discuss bilateral ties. But the reality is that this may be difficult to do in some cases. The fact is that the United States and China operate very differently as countries, including in how they approve foreign assistance. Washington has more strings attached to new aid it can provide in sensitive areas, and it may take a long time before fresh funding is approved depending on the channel in question.

For example, while China and Chinese businessmen have already moved forward with visibly greater cooperation with the Philippines on drugs in spite of rights concerns – including the construction of a rehabilitation center – the United States would not be able to do so in a similar manner and to the same degree, and even if it does try to boost cooperation, it cannot stay silent on the concerns that are part of its long-held ideals.

“We’re not a command kind of economy or government, so we have to think these things through,” outgoing U.S. ambassador to the Philippines Philip Goldberg said in an interview with local media outlet Rappler on Thursday.

“We have certain laws, certain obligations under U.S law to follow,” he added.

One also needs to entertain the possibility of scenarios that are a little more mixed and more difficult to manage. For example, we could enter a scenario where Duterte continues to advertise his pivot to China while having fierce public disagreements with the United States over a range of issues, even as selective U.S.-Philippine cooperation in certain areas is ongoing but remains under the radar. This could either occur with or without Duterte’s knowledge. Indeed, Duterte’s lack of foreign policy experience arguably increases the chances of this scenario occurring, since he may continue to rail against bilateral security cooperation, but then actually not follow through on severing ties at the working level. The situation would then somewhat resemble what we saw in U.S.-Malaysia relations under Mahathir Mohammad in the 1980s and 1990s.

Though this would not be an ideal scenario for the United States given where it started off at the end of Aquino’s tenure, it would at least limit the damage on U.S.-Philippine security ties as Washington awaits a friendlier administration that is willing to boost ties. In the meantime, Washington could continue to look for other opportunities to ‘balance’ Manila’s ‘rebalance’ to China, including through its principled security network. Indeed, one of the most underappreciated advantages that the United States enjoys is its wide range of allies and partners, whom it can draw on to forge cooperation indirectly with others even if its own reach is curtailed.

Conclusion

Duterte’s ongoing U.S.-China ‘rebalance’ has understandably dominated conversations about the region over the past few months, and it may even intensify in the short term. But irrespective of the fate of this ongoing realignment, observers should be clear not just about the opportunities that are available, but also the limitations that exist.

Prashanth Parameswaran is Associate Editor at The Diplomat Magazine and a PhD candidate at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. He writes extensively about Southeast Asia, Asian security affairs and U.S. policy in the Asia-Pacific.