The first major Quran exhibition in the United States opened its doors in Washington, D.C., this weekend, at the Smithsonian Institution’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of Art. The exhibit, entitled “The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts,” goes on display at a timely moment, amid the lively political debate over the nature and place of Islam in the United States. Unfortunately, over half of the American population has an unfavorable opinion of Islam. It is to be hoped that this exhibition will do its part in introducing more Americans to an appreciation of Islam, via, in this case, the Quran.

The Quran is the holy book of Islam, revered by more than one billion Muslims throughout the world. All the Qurans at the exhibit, numbering around sixty, were on loan from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts in Istanbul, Turkey. The Qurans included ranged from the Umayyad (661-750 CE) era to the Ottoman (1299-1923) Dynasty, and came from Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Iraq, and other places. At some point, the Qurans in the collection were acquired by members of the House of Osman, the Ottoman royal family.

Each Quran’s journey to the Ottoman family is an interesting tale; these stories shed light on related historical events and social and economic trends. Many Qurans show the seals of the owners, libraries, mosques, or other institutions they had passed through, making their journeys traceable. By way of example, there is a gilded Quran in the exhibition that the Ottomans acquired in Yemen after their conquest of that region in the sixteenth century.

The Quran was placed, as a blessing, in the mausoleum of Ottoman Sultan Murad I (reigned 1362–80) in Busra. The Quran itself was originally copied in Cairo, Egypt, during the Fatimid period (909-1171 CE) in 1028, when the Ismaili Shia Fatimid dynasty was preeminent throughout much of the Islamic world. According to the Smithsonian Institution:

…as a symbol of Fatimid religious authority and political power, Caliph al-Mustansir bi’llah presented this manuscript to Ali al-Sulayhi, the Yemeni ruler of the Sulayhids (1047–1138). The exchange likely took place in 1062, when al-Sulayhi pledged religious and political allegiance to the Fatimid caliph. After that, the lucrative trade routes of the Red Sea and Indian Ocean, which the Sulayhids controlled, became integrated within the larger Fatimid sultanate.

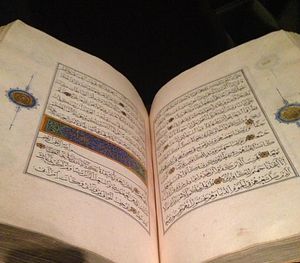

As I’ve written before, the Quran is a breathtakingly poetic and beautiful book, “melancholic, wistful, and sharp.” Moreover, Qurans are works of art, as the exhibit demonstrated. They served as talismans, decorations, and markers of prestige, in addition to being read. Individual Qurans are gilded, bound, and illuminated in a variety of ways, many of which often mark the era and place where they were copied. The Qurans on display came in a variety of shapes and sizes. Some manuscripts were pocket-sized or even contained just portions of the Quran for reflection. One Quranic verse, about light (Surah 24:35), on display was not even on a manuscript but inscribed on a lamp. At the other end of scale, of particular interest, was a giant Quran created for the Central Asian conqueror Timur; each page measures five feet by seven feet.

Additionally, different Qurans were and are copied using different calligraphic scripts, and calligraphic masters, making each Quran distinct and unique. In general, Arabic writing has grown more curvaceous and flowing over time (though previous styles were still used as new ones developed), from the angular Kufic script of the Umayyads to the airy quality of the Nastaliq script commonly used in the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal empires after 1500 CE.

Despite the text of the Quran being the same in all the books at the display, there is an amazing variety of styles of beautiful art at the display. Both those new to the art of the Islamic world and those familiar with it will discover something new and interesting at this exhibit. A visit is highly recommended–but one should make haste, as the exhibit will only be at the Smithsonian until February 20, 2017.