After weeks of siege in Lanao del Sur’s Marawi City and the declaration of martial law in Mindanao on May 23, the situation in the Philippines grows direr by the day. The Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) have not yet subdued the Maute Group-led force of around five hundred militants, and much of the nation waits anxiously while President Rodrigo Duterte flirts with the declaration of martial law nation-wide. Even though news of Marawi City siege has understandably captured the public’s attention, we should not forget that although the Philippines struggles with jihadism and Southern Philippine Muslim (Moro) separatism partially resulting from the ailing Moro peace process, the government is still trying to end its other long campaign against the New People’s Army (NPA).

A Process Eclipsed By Crisis

As of this writing, talks between the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) and the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) are in limbo. The GRP has officially cancelled their 5th round of formal talks under the Rodrigo Duterte administration, but negotiators have not yet given up. A coalition representing the interests of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and the militant New People’s Army (NPA), the NDFP sought for decades to implement Maoist reforms in the Philippines through negotiations coerced by the NPA’s ceaseless guerrilla campaign, to little avail. Now that martial law has come to Mindanao for the third time since the dictatorship of President Ferdinand Marcos, the CPP-NPA vows to increase its offensives and resist martial law while the NDFP exhorts them to stay their arms.

Some in Congress are unperturbed by the suspension of talks, believing negotiation to be a futile enterprise for numerous reasons, the foremost being widespread skepticism of the NDFP’s influence over the NPA in the field. On May 10 Professor Jose Maria Sison, a founding member of the CPP-NDFP-NPA, issued a cryptic warning to reporters after a spate of NPA attacks, saying “No one in Utrecht can give orders to the CPP [Communist Party of the Philippines], NPA [New People’s Army], NDFP in the Philippines…” Joma is likely correct when he says the NDFP does not directly control the NPA, but the NPA is not wholly disinterested in political developments outside of its cantonments.

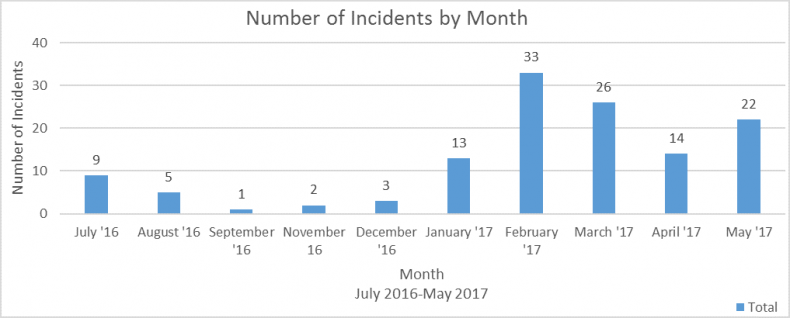

Based on the data my Manila-Based colleagues, Angelica Mangahas, Jasmine Torres, and I collected, some of which is presented in the graphs that follow, the NPA commands of the Southern Philippines demonstrated a capacity and willingness to curtail its operations pursuant to the declaration of ceasefires and the resumption of formal talks by the GRP and NDFP. Though the preconditions for failure were building from September through December, it was only in mid to late January that the NPA resumed hostilities en masse. By April, incidents linked to the NPA declined in tandem with news that formal talks between the GRP and NDFP will resume, but violence continues nonetheless. Generalizing about a decades-long insurgency is an analytically reckless thing to do, but I believe these observations are borne out by the scrutiny of our data.

Admittedly, our data is little more than a snapshot of the region, and suffers from three notable limitations. First, it only covers the southern Philippines (Mindanao, Tawi-Tawi, and Sulu). Our research was originally conceived as a database of Moro-related political violence, hence the focus on this region, but expanded to include other groups like the NPA. Second, the data is conservative, as it comes from national and local media sources, activist groups, and press releases from rebel and state authorities, but we lacked access to useful primary sources. Third, the incidents recorded in the data are only those in which the NPA was reasonably identified as a belligerent. The overwhelming majority of attacks we’ve recorded in the southern Philippines were attributed to unknown perpetrators. In these cases groups like the NPA may be suspected, but without additional evidence we consider these incidents to be separate from our NPA count. In sum, our data likely understates the violence perpetrated by the NPA.

The NPA in Numbers

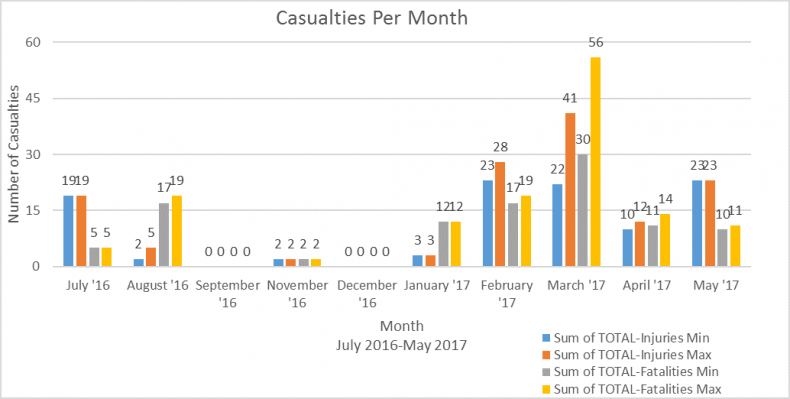

From July 1, 2016, the day after President Duterte’s inauguration, to April 30, 2017, there were 128 incidents involving the NPA in the southern Philippines. These incidents resulted in between 104 to 133 injuries and 104 to 138 deaths among insurgents, soldiers, and civilians combined. Duterte, a self-proclaimed leftist originally from Mindanao whose election buoyed hopes of a successful peace process, has thus far failed to meet this lofty expectation.

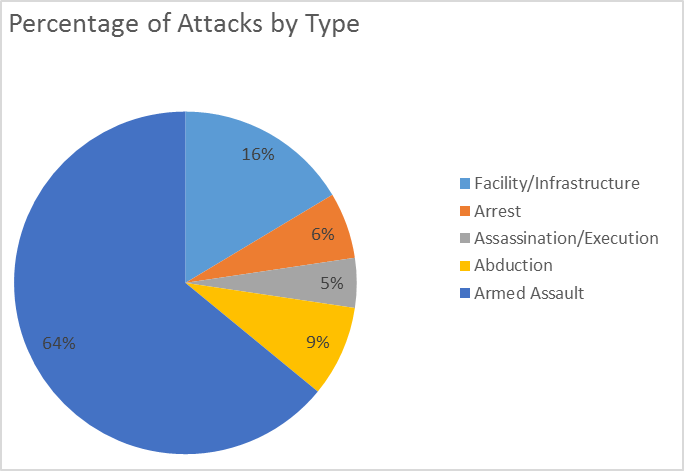

Sixty-four percent of recorded incidents were armed assaults involving the exchange of small arms fire (at minimum) between the NPA and other actors, 19 percent were attacks on facilities or infrastructure such as mining sites, plantations, and vehicles, while the remaining incidents entailed abductions, arrests, and assassinations/executions.

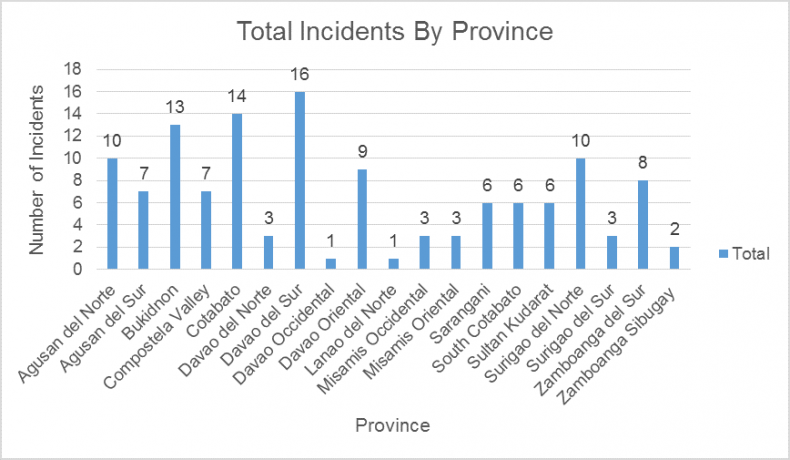

Geographically, the provinces of Davao del Sur (including Davao City) suffered the highest number of incidents, though Cotabato and Bukidnon were not far behind. Davao Occidental and Lanao del Norte endured only singular incidents, while provinces like Sulu and Basilan recorded none.

Trends and Observations

Upon taking office President Duterte faced an active NPA. On July 5, the NPA and the AFP engaged in a firefight near Bayog, Zamboanga del Sur that killed two rebels and an AFP-aligned militiaman. Although Duterte declared a unilateral ceasefire on July 25, he revoked it as incidents occurred through July and into August. Violence for the remainder of August abated, and on August 20 the NDFP/NPA declared a unilateral ceasefire. Formal talks between the GRP and NDFP began on August 22, and an indefinite ceasefire deal was signed on the 26th. Subsequent incidents from September to December entailing an abduction, firefights, and attacks on property were very infrequent, and only one entailed any loss of life.

Between January 16 and February 1, the NPA was involved in 15 incidents, nine of which occurred on January 30. Around the same time, talks between the NDFP and GRP proceeded in Rome from January 19-25, which involved discussion of the implementation of the NDFP’s socioeconomic reform program. Though the talks were considered productive by all parties, it resulted in few concrete concessions by either side. In particular, the GRP still refused to release 392 NDFP prisoners from custody until the issue of amnesty was fleshed out

On January 30, the NPA broke the ceasefire with simultaneous assaults in Mati, Surigao Del Norte, Valencia City, Bukidnon, Pag-asa, Lebe, Sarangani, Union, Compostella Valley, San Isidro, Mahayahay, and Hinambangan, Kitcharao, Agusan Del Norte. Subsequently, on February 1, the NPA called off its unilateral ceasefire, citing the failure of the GRP to release their political prisoners and generally abide by its ceasefire. By February 3, Duterte withdrew the GRP from its ceasefire in response.

From February (30 incidents) through March (26 incidents), violence occurred with almost daily regularity. Among the most significant was a February 16 encounter between the NPA and AFP within Davao City. By day’s end 14 to 15 soldiers were wounded and two were dead, while the NPA suffered between one and three fatalities. March was especially bloody due to a series of encounters in Kalamansig town, Sultan Kudarat that lasted from March 16 to 21. Following the Kalamansig clash, a two-day encounter spanning March 20 and 21 yielded nine injured NPA fighters and eight killed by firearms and artillery, while the NPA had eight wounded and eight killed. Afterwards, the casualty rates for March remained low but consistent.

April’s numbers of incidents and casualties declined substantially from the highs of the previous months. Nine out of the 14 incidents recorded in April occurred during the first two weeks of the month, while the rest were clustered from the March 22 to 29. Though it is difficult to prove, one explanation for the drop in violence was the bilateral interim truce negotiated in early April during a nonstop series of informal talks between the two parties. Whatever its impact, the truce did not last long given the almost daily frequency of firefights between the NPA and security forces during the first weeks of May. These incidents were low intensity, with the exception of a series of clashes in Davao City on May 10 through May 11, leading to the deaths of one soldier and two rebels, in addition to nine wounded soldiers. Incidents surged again after Duterte’s May 23 declaration of martial law with two bombings and six armed assaults that claimed no lives, but wounded several on both sides.

Explaining Patterns

Although the data are drawn from a sample that is relatively small and geographically limited, there are prima facie correlations between the status of peace talks and incidents on the ground. First, incidents during the July/mid-August range plus Duterte’s aborted July ceasefire suggest that Duterte’s “good faith” toward the NDFP did not immediately translate into an abatement of NPA-related violence in the south. With the declaration of unilateral ceasefires on both sides and the commencement of formal talks, incidents dropped off precipitously into January. It should be noted that this period was not without tension. The NPA decried the presence of troops in territories they claimed to control, asserting that the AFP was exploiting the ceasefire to collect intelligence and gain a sturdier footing in rebel-claimed areas. The AFP, in turn, accused the NPA of continuing banditry, extortion, and the coercion of locals to prepare for another round of fighting.

Nevertheless, the recorded incidents did not become especially worrisome until the drastic escalation on January 30. These simultaneous attacks heralded the NPA’s decision to withdraw from the ceasefire the next day on February 1, which in turn prompted the GRP to abandon the ceasefire as well. With no ceasefires, the dramatic increase in incidents in February and March was predictable. Only through back channel talks, the resumption of official negotiations, and the announcement of a truce did the levels of violence subside slightly before escalating again in May. Preliminary data for June suggests that the NPA is curbing its aggression to sporadic skirmishes, while they assess the possibility of future talks, as well as the quality of AFP operations around Marawi City.

So long as the violence continues and official negotiations remain off the table, hope for a lasting settlement fades further and further away. As the data strongly suggests, the NPA of the Southern Philippines is clearly capable of abiding, for the most part, by the terms of a ceasefire. That said, NPA field commands have a limited tolerance for the presence of security forces within their “borders” and continue to subsist off of the extortion of populations therein. Both of these factors motivate the NPA’s use of violence, making the brokering of a durable ceasefire without tangible political dispensation for a ceasefire almost impossible.

When the August 2016 ceasefires were called off, they were preceded by tensions on the ground and a lack of results at the negotiating table, in particular the failure of the negotiating panel to secure the release of political prisoners. Thus, we should not be surprised that the NPA has bucked NDFP pressure to accede to a formal truce. To make matters worse, Duterte oscillates his behavior towards the NDFP-NPA with threats and inducements. On one day he invited the NPA to come and join him at his dinner table, while on another he threatened to incarcerate members of the NDFP’s negotiating panel. Duterte’s madcap statecraft may be a methodical approach to negotiation, but to most observers Duterte is a manic strongman and an unreliable partner for peace. However unstable, even Duterte should understand that the AFP is stretched thin containing the Maute-led takeover of Marawi City, and is ill-prepared to counter an NPA offensive in Mindanao, to say nothing of the rest of the country. Should the peace degrade further and the NPA press the beleaguered AFP, the outcome will be assuredly tragic.

Luke Lischin is an academic assistant at the National War College.