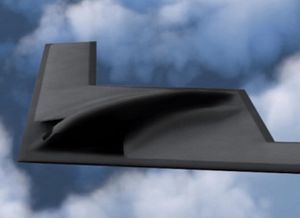

Late last month, the Center for New American Security (CNAS) released a new report from Jerry Hendrix and James Price on the history of strategic bombing, and on the place that the Northrop Grumman B-21 “Raider” will occupy in the lineage of strategic bombers. Reminiscent of Jerry Hendrix’ structurally similar report on the history of the carrier air wing, and the place of the CVN-78 carrier in U.S. naval doctrine, the report concludes that the U.S. Air Force may need more Raiders (164) than it currently expects to acquire (100).

Unfortunately, the strategic bombing paper lacks the tight analytical hook of the earlier report. The carrier air wing built a coherent narrative around the idea that the relative ranges of land-based aircraft and carrier-based aircraft told us something useful about the effectiveness of the latter, and made a compelling case that this relationship held irrespective of the characteristics of specific aircraft or aircraft carriers. The report had deep roots in the Navy’s own understanding of the value of a carrier air wing, but did not shy away from criticizing decisions that the Navy had made, or was about to make.

The strategic bombing report, on the other hand, simply recapitulates a series of Air Force stories about strategic bombing. Indeed, the first 40 pages of the report have little to do with the B-21, instead offering a tendentious recounting of the history of the American heavy bomber. The report accepts the Air Force perspective on the heavy bomber as its own, failing to delve into or take advantage of the vast literature on the successes and failures of strategic bombing in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam.

For example, while the authors discuss some of the problems associated with daylight precision bombing over Europe, they fail to engage with larger questions about the cost and effectiveness of the campaign, instead citing the post-war Strategic Bombing Survey (a document explicitly intended to win the Air Force its independence) as factual evidence of effectiveness. In the case of Vietnam, they dismiss the large literature associated with the Rolling Thunder and Linebacker II campaigns in favor of rote assertions about the technical effectiveness of heavy bombers.

This may seem like nitpicking, but if the story of strategic bombing is to be retold in service of a policy recommendation, then it needs to be retold as carefully and accurately as possible. Citing Linebacker II as a success story for heavy bombers does violence to both the technical and political details of the 1972 campaign, but the authors breeze past the point on their way to the B-1B.

The trip down memory lane is fun, and Hendrix and Price do a good job of sketching the technical questions that characterized each generation of heavy bomber. But by their own account, Hendrix and Price expect the B-21 to undertake different missions than any previous “bomber.” This includes acting as a vector for sensors and communications in a broader effort to penetrate an anti-access system, as well as conducting conventional counterforce attacks against enemy defense installations, a mission not associated with any of the strategic bombers they include in their study. This has consequences; if we evaluate the contribution of the B-21 in the same terms as we evaluate the various missions of its distant ancestors, we run a serious risk of misunderstanding what the bomber offers.

Overall, the report is disappointing. In mission profile the B-21 bears little resemblance to the B-36 in any sense other than it is a large military aircraft with a “B” in front of a number. A sensible retelling of the history of the U.S. Air Force’s experience with strategic bombing would indicate that this is almost certainly a good thing; the farther away the B-21 can be distanced from the technical and doctrinal failures of the U.S. Air Force’s bomber corps, the better. There is a good case to be made for the B-21. Weighing the bomber down with generations of strategic bombing theory, however, does it no favors.