Last Wednesday, Xi Jinping set out his vision for China’s future in a three-and-a-half hour long report to the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

At around the 173 minute mark of this marathon recital, Xi launched into the report’s twelfth and penultimate section, entitled “Adhering to the Path of Peaceful Development and Constructing a Community of Common Destiny with Mankind.”

Many analysts have written about the arrival of Xi’s “New Era” in China. Fewer have explored the report’s foreign policy implications, and fewer still have noted the importance of this pivotal phrase, “community of common destiny.”

Foreign policy rarely gets much of a look in at Party Congresses, and Xi’s section on foreign affairs followed the pattern of past reports in being brief and stocked with generalities about peace and development.

But this shouldn’t be read as a statement of total conformity. The global China portrayed by Xi very much belongs to his “New Era.”

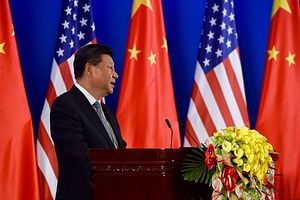

Xi Jinping’s Assertive Foreign Policy

Under Xi Jinping, China’s foreign policy has departed from Deng Xiaoping’s reform era dictum to “…hide our capacities and bide our time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership.”

Instead Xi has advocated fenfa youwei, or “striving for achievement”, and has made active calls for greater Chinese leadership in world affairs. Over the past five years, new policies have been combined with new institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and new initiatives like the Belt and Road, to build what Xi Jinping refers to as a “community of common destiny.”

But, like many of the developments that distinguish Xi’s era, this newly assertive foreign policy should be read in the context of the Party’s historical mission to achieve “national rejuvenation.” Xi’s leadership marks a continuation of, rather than a radical break from the past, and much of the groundwork for Xi’s new foreign policy had been laid by Hu Jintao in his 2012 Party Congress Report.

Hu Jintao called on China to take “an active role in international affairs, and work to make the international order and system more just and equitable.” Xi Jinping says that China will “play its part as a major country and take an active part in reforming and developing the global governance system.” The difference is subtle, but significant. The China portrayed by Hu Jintao is growing in confidence, whilst there is no doubt that Xi’s China is already a great power with the ability to influence the international order.

“Community of common destiny” also makes its first appearance in Hu’s report, where he recommends raising awareness of a “community of common destiny” amongst China’s neighbors.

For Xi, “community of common destiny” means something more. In Xi’s “New Era,” fostering a ‘”new type of international relations” and building “a community of common destiny with mankind” is the primary aim of Chinese foreign policy.

It is easy to dismiss such rhetoric as empty propaganda. To the cynical Western mind, oft-wheeled out phrases like “win-win cooperation” and “peaceful development” form part of a meaningless lexicon of diplomatic jargon.

But such slogans are not used without purpose. Theory and ideology are more important to the CCP than an international audience might be led to believe, and so are its banner terms, which play an important role in wider policy implementation. Xi spent most of his report talking about the theoretical underpinnings of the Party; such dedication to theory is not purely window-dressing.

Given the centrality of phrases like “community of common destiny”, we should at the very least consider their origins and what they mean to the politicians that use them.

The Origins of “Community of Common Destiny”

“Community of common destiny” has a curious pedigree. The history of its intellectual transmission can be traced back to Ernst Renan’s Qu’est-ce qu’une nation? (What is a Nation?), which proposed the idea that nations are not held together by ethnicity or culture, but by a deeply felt sense of community and shared destiny. Xi Jinping is now applying the same concept in an international context.

Xi’s Party Congress report was not the first to define Chinese diplomacy in terms of aspiring to a “community of common destiny.” At the Conference on the Diplomatic Work with Neighbouring Countries in 2013, Xi set out China’s new neighbor-centric foreign policy, also known as China’s “peripheral diplomacy.” In his speech, Xi echoed Hu Jintao’s rhetoric, saying that Chinese diplomats should “[let] the awareness of community of common destiny take root in neighboring countries.”

At the Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs in 2014, Xi went a step further, explicitly stating that China’s goal is to “turn China’s neighborhood areas into a community of common destiny.” The 2014 conference reaffirmed China’s focus on its periphery, but it also defined that focus as the effort to build a “community of common destiny.”

But “community of common destiny” is not just about peripheral diplomacy. It is central to China’s wider foreign policy. As Vice Minister Madame Fu Ying writes in The Diplomat, promoting a “community of shared future” is also the ultimate objective of China’s Belt Road Initiative (“community of common destiny” and “community of shared future” are two official translations of the same Chinese phrase).

Over the past five years, Xi has used the term countless times in a number of high profile speeches, each time widening the scope of the “community of common destiny,” from regional to global, and increasing the place of prominence afforded to the concept.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Xi vehemently defended economic globalization at a time when events of mid to late 2016 had eroded the global credibility of the Western leadership. At Davos, Xi expounded China’s “goal of building a community of shared future for mankind,” and later, after a keynote delivered to the UN entitled “Work Together to Build a Community of Shared Future for Mankind,” the concept was enshrined in a UN Human Rights Council resolution.

What Does “Community Of Common Destiny” Mean?

In short, “community of common destiny” describes a world defined by mutual cooperation. It also describes a “new” approach to international relations that supersedes an “outdated” model associated with the West.

In a semi-official book on the Belt Road Initiative (BRI), former diplomat and prominent scholar Wang Yiwei describes how BRI promotes the formation of a “new global and economic order.” Wang writes that this “new order” is a “community of common destiny,” which “embodies China’s understanding of power, stressing equality and fairness.”

According to Wang, a “community of common destiny” is achieved through creating both a “community of shared interests” and a “community of shared responsibilities.” The “community of shared interests” roughly corresponds to a situation of economic interdependence, or “completing each other economically.” The “community of responsibility” refers to the political and security realms, or a situation of “complete political mutual trust.”

Like Xi’s “new era”, and his “new model of great power relations,” “community of common destiny” is also about novelty. “Guo Jiping” (a psuedonym used for explaining international issues in the People’s Daily) writes that the concept, “by means of win-win cooperation, embodies a new type of international relations.”

In the wider academic literature and in Xi’s own speeches, this new model is set up against the “old model” of international relations, which is associated with the United States and Western powers. Whereas the “community of common destiny” is premised on “win-win” relations, the old model is governed by “zero-sum” thinking, and what Xi calls a “Cold War mentality.”

According to Wang, “destiny community” is novel because it transcends the “mentality” that has occupied human history for thousands of years – that of “my interest comes first.” The claim is bold: the “community of common destiny” transcends the normal operation of self interest in international politics.

A “New Era” for International Politics

Xi Jinping’s Party Congress report is the latest and by far the loudest statement of this new foreign policy concept. Officially, “community of common destiny” has now been written into the Party constitution as a defining aspect of “Xi Jinping Thought.” It’s therefore no exaggeration to say that “community of common destiny” defines Chinese foreign policy in Xi Jinping’s “New Era.”

In a thinly veiled reference to Trump’s America, Xi’s report made the point that “no country alone can address the many challenges facing mankind, and no country can afford to retreat into self isolation.” Meanwhile, Xi promised that China would “reject the Cold War mentality and power politics,” instead offering to build a “community of common destiny for mankind.”

Both Xi’s and Hu’s work report made the same generic promises to “hold high the banner of peace, development, cooperation, and mutual benefit,” but Xi has gone much further in implying that the Party, and Xi Jinping Thought, are not only China’s salvation, but the world’s.

Xi said that China’s model provided a “new option” for “developing countries” to “achieve modernisation … while preserving their independence.” Building on Hu’s nascent vision of a global China, Xi claimed that “Chinese wisdom, and the Chinese approach” now offers a unique solution “to the problems facing mankind.”

The message is clear. Domestically, China is entering Xi Jinping’s “New Era,” but Xi has also provided a path for China’s leadership of the wider world into a global “New Era.” A “community of common destiny” is the final destination that Xi has in mind, and the prominence of this concept is a good measure of Beijing’s growing confidence.

When Xi boldly states that China will be “reforming” international governance, it is through this concept that we should understand Beijing’s plans for our future.

Jacob Mardell is a Chinese studies postgraduate student at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. He runs the blog “The China Road.”