The first shipment to pass through the port of Chabahar to Afghanistan was celebrated with much fanfare and excitement this late October. India, with the largest economy in South Asia and an ever-rising military footprint has much to be proud of regarding this development. In the face of regional tensions with its western neighbor, Pakistan, India has chosen to circumvent the nation in order to open new trade routes with Afghanistan and greater Central Asia. Delhi may now find it easier to further diversify its trading partners, strengthen its relations with regional neighbors, and simultaneously compete with China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

While the potential for Chabahar’s positive externalities remain numerous, they also remain largely hypothetical. The completion of the project does not necessarily guarantee an increase in Indian economic influence, considering the economic and political realities that Delhi presently faces on the domestic front and in the region. The competitiveness of Indian exports, the security situation in Afghanistan, and regional geopolitics pose several hurdles that India must overcome.

Domestically, India faces a slowing economy that has had six continuous quarters of decreasing growth. The economy rebounded in the latest quarter but growth forecasts for the economy continue to be revised downwards due to recent poorly executed economic reforms (the Goods and Services Tax and demonetization). This becomes further troubling as the Indian economy continues to be faced with a critical job shortage that must incorporate 12 million young people every year. Additionally, India’s banking sector continues to pose risks to the economy with non-performing assets (bad loans) continuing to rise to unprecedented levels. In light of domestic economic challenges, Delhi would be wise to draft a comprehensive economic strategy to justify the cost of the overall investment in Chabahar and the overall multinational initiative.

Currently, India has allocated around $2 billion to the overall project — $500 million dollars has been allocated to the construction of Chabahar port to increase cargo handling capacity and $1.6 billion to the construction of a rail link that will connect the port to the city of Zahedan. The city borders Afghanistan and will allow goods to flow into the country through already built infrastructure. Chabahar port will also serve as a starting point for the over-arching International North-South Trade Corridor (INTSC) that aims to connect India, Iran, Russia, and various Central Asian states. Remarks by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and various analysts claim that the new port will revolutionize trade and commerce. This may prove to be true if India is able to drastically improve the efficiency of its manufacturing sector and increase the demand for Indian goods.

Yet, the current status quo will prove difficult to change considering both the cost and share of total exports India sends to Central Asia (including Afghanistan) when compared to other nations, specifically China. In early July, the Minister of State for Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises, Haribhai Chaudhary, was asked why domestically produced goods cost more than those imported from China. Chaudhary responded, “The products manufactured in China are reportedly of lower price mainly because of their opaque subsidy regime and distorted factor prices.” India’s economy is primarily based on the services industry, which composes more than half of its GDP, compared to industry (including manufacturing), which only composes a little more than a quarter. China’s economy on the other hand, is primarily composed of industry, giving it greater leverage and ability to compete with Indian goods.

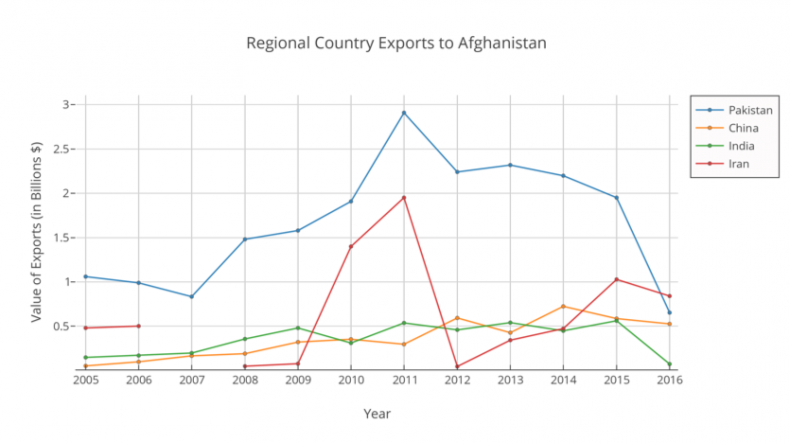

In 2015, India exported a total of $950 million worth of goods to Central Asia compared to China’s $18 billion. The majority of Indian exports were sent to Afghanistan valued at $560 million. Yet, Afghanistan’s trade statistics over the past five years, due to the departure of American and NATO forces, have seen an average yearly fall of imports of around 50 percent. Afghan exports have also dwindled from a high of $531 million in 2011 to $482 million in 2016. As a result, the value of Indian exports to Afghanistan has dwindled to a fraction of the overall 2015 amount, falling to $73.6 million in 2016. It should be noted that India not only has to compete with Chinese exports, but also with the exports of Afghanistan’s immediate neighbors, Pakistan and Iran, if it hopes to maximize its investment in Chabahar.

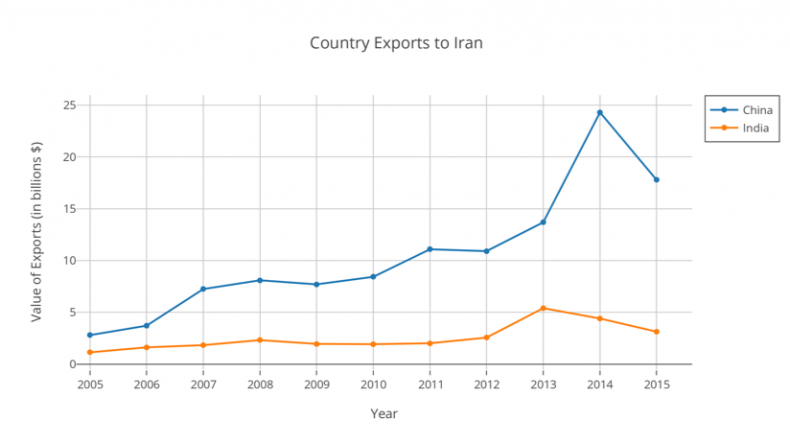

Figure 1: Statistics obtained from Organization of Economic Complexity (Iranian trade figures from 2007 are unavailable)

Current trade figures between Indian and Chinese exports to Iran and Russia further indicate the imperative for Delhi to develop a comprehensive trade strategy. In both Russia and Iran, the market share held by Chinese exports dwarfs those of India.

In 2005 and 2006, the gap between Indian and Chinese exports was marginal. Yet, this margin rapidly rose, with China’s market share in the Iranian economy coming to dwarf India’s. Indian exports reached their peak in 2013, standing at around $5 billion. A starker contrast is revealed when comparing the market share that Chinese exports hold in Russia compared to those of India. India must create a niche for its goods so that they can rival cheaper Chinese produced goods.

The second major challenge that India must overcome deals with the security situation in Afghanistan that may complicate the success of the port. Delhi must find a method to safeguard goods as they are transported through Iran and into Afghanistan. Once the rail line from Chabahar to Zahedan is completed, goods will travel by an already built rail system to Afghanistan and Iranian road networks, giving India access to the four major Afghan economic centers: Herat, Kandahar, Kabul, and Mazar-e-Sharif.

However, India must go through districts that are either under Taliban control (44 districts) or currently contested (117 districts). The security situation in Afghanistan continues to deteriorate as the Taliban continues to gain an ever-stronger foothold through out the country. This year’s release of the report by the U.S. Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) has chosen to redact the number of Afghan army and police that have been injured or killed, the overall number of security forces, and their overall progress. What is even more alarming is that these figures, previously public, have been withheld at the behest of Kabul. Will Delhi have to cooperate with the Taliban to ensure the safe transit of goods? What role will Kabul have in any possible discussions?

The last major hurdle that India faces is navigating both the economic and geopolitical competition within the region. The port of Chabahar will have to compete with the joint Pakistani-Chinese port of Gwadar, which is seen as a crucial pillar to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and China’s BRI, as well as the Iranian port of Bandar Abbas. Gwadar port, currently in its initial stages, is expected to handle one million tons of cargo by the end of 2017, 13 million tons by 2022, and a staggering 400 million tons by 2030. China and Pakistan are unlikely to sit idle in the face of the massive investment that has taken place.

Geopolitically, India’s investment in Iran seems to be counter to U.S. interests. The current U.S. administration’s antipathy toward the Iran nuclear deal and the imposition of additional sanctions pose questions regarding the viability of India being able to balance good relations with both Washington and Tehran.

Chabahar port and the overall North-South Trade Corridor are crucial steps to increase Indian economic influence and further link regional nations through trade. Yet, the successful completion of these goals depends on Delhi’s implementation of a sound economic and political strategy to maximize the benefits it may receive from the overall project.

Ali Malik is a research consultant at the Stimson Center in the South Asia Program.