Before going on a trip, we usually arm ourselves with a map that offers visible, concrete, clear-cut lines. Regions, neighborhoods, and human societies seem to be neatly divided and separated by borders. During the journey, however, we may find out that some of the lines are actually artificial; the divisions may become blurred. A similar mental map often exists in our heads. We tend to have notions of a mapped humanity, with lines cutting across people and putting them into different categories: the classes, the castes, the races, the Pole and the Jew, the Hindu and the Muslim. These categorizations serve their purposes up to a point, but they can be equally misleading; like a map with thick lines they show us general tendencies, but once we set out to know more about a chunk of our social reality, it usually turns out to be much more complex.

A few years ago I visited a village outside Delhi, in the state of Haryana. There is a tomb of a Hindu saint there, I was told, and the local inhabitants seek his blessings. The tomb turned out to be a small building with a white dome and a simple, white tomb inside. A perfect example of Muslim architecture, save for the fact that there were figures of Hindu deities inside and the wall around the tomb had swastikas carved on it, a later addition. Upon asking why there was a tomb given that Hindus usually (though not always) burn the bodies of the deceased, I was told that this particular holy man could not have been burned, as his mortal remains were miraculously swallowed by the earth upon his death. The saint, the local myth says, took the sins of the people into the soil and thus cleansed the men of their past misdeeds.

Most of the cult sites in India – temples, churches, mosques, ponds, springs, and many others – have a clear religious affiliation and we usually can assume the religion of the majority of the people frequenting them. Yet, there are also places where the lines blur.

Yoginder Sikand’s Sacred Spaces. Exploring Traditions of Shared Faith in India is a book that tells the stories of some such cults. For example, a person that supposedly once appeared in a place called Vailankanni in the state of Tamil Nadu is worshiped as a goddess by local Hindus, and as Mary by local Christians.

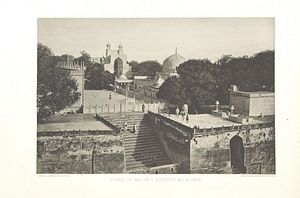

More often, the cult places that exist at the borderlines between religions are the tombs of saints, particularly Muslim Sufi saints. Sufism could have been attractive to some Hindus. In some regards it is more heterodox than more fundamentalist trends in Islam; it stresses a more personal relation between a believer and God (and thus clergy is less needed), and it believes in the power of the blessing of the holy man (something that Hindus generally believe as well, while Muslim orthodoxy rejects it). This does not mean that the Sufi saints were not Muslims and they did not criticize other religions like Hinduism — they often did — and yet some centers of Sufism were frequented by some Hindus. Even today some of the tombs of Indian saints, many of them Sufis, still attract pilgrims from the other faith, even if they are in a minority. That is the case for Ajmer Sharif, the tomb of Sufi saint Moinuddin Chishti (the first Sufi saint that had come to India) in Ajmer, or the tomb of Nand Rishi in Charar-e Sharif in Kashmir.

Some of these places, however, have not retained their eclectic character, and have been homogenized into being exclusively Hindu or Muslim. The influences of orthodox groups on both sides and the long, sorrowful, and bloody story of Hindu-Muslim tensions are possible explanations as to why this has happened. Many from orthodox and radical Muslim and Hindu groups do not want to admit that a particular place used to be influenced by two different religious traditions. In some cases, a tomb that had been claimed by one community has suffered the erasure of the visible signs of another faith’s influence. After a generation or two, a new narrative of the homogenized cult takes over, and it is hard to know or prove that a particular saint was, for instance, a Muslim. This happened to the tomb of Baba Rattan in Bhatinda in Punjab, which has become an exclusively Sikh place of worship. A similar case is that of the first Sai Baba who, despite the contemporary narrative which portrays him as a Hindu, was most probably a Muslim. Mental maps are drawn, the lines are clear, and we find comfort by ignoring the blurred sections.

Nevertheless, some clues are still to be found. One of the places associated with Sai Baba and his life is still referred to as a “mosque” by at least some of his Hindu followers, though in this case they do not interpret the word “mosque” (masjid) as a “Muslim” one. In Jhandewalan, a Delhi neighborhood which now has a strong presence of Hindu nationalists, there is a Hindu sacred place called the “Dargah Pir Ratan Nathji.” The word dargah usually denotes a tomb of a Sufi saint, and pir – spiritual teacher – is a way of titling a Sufi saints.

When homogenization of a place of shared faiths takes place, the symbols of the other religion which the radicals find embarrassing, if not erased, are often explained in clever ways; new myths are devised to cover up the old ones.

This must have happened with the tomb of the “Hindu” saint I saw in that village in Haryana. Since it is a tomb with a body, somebody must have come up with the story of the earth swallowing the mortal remains, so that burning was not possible (though it is possible that in this case no Hindu radicals were involved: just ordinary Hindus seeking to find explanations for the particularities of their cult place).

The rites of passage, such as those connected with the death, are often treated as markers of one’s identity. One is reminded of the story of the famous Indian saint Kabir, who was followed by Hindus and Muslims alike, and who criticized the blind orthodoxy that was to be found in both religions. When he died, a question inevitably arose: what to do with the body? A legend tells of the compromise. The body, the story goes, turned into flowers. Thus, the Muslims were able to bury half of them, while the Hindus burned the other half. A similar story is told with regard to the woman saint Lal Dhed of Kashmir.

It is striking that some people can look at a place and not see these signs of shared and mixed history. For example, that a building is clearly of Muslim architecture or is called a mosque, but yet is considered to be a place of Hindu worship. At other times it is precisely the same signs that lead us to quickly and easily label a place as belonging to a particular religion. As the number of shared faith cults dwindles in India, such places should be upheld as symbols of communal harmony, and their homogenization should be resisted, rather than ignored.