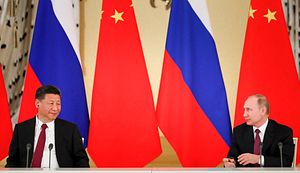

As Putin has become the longest-serving Russian leader since Stalin, the country’s economic and political stagnation is drawing more and more comparisons to the Leonid Brezhnev era. Putin’s political system cannot survive the stresses imposed by major reforms needed to improve the economy, creating a deepening dependency on foreign policy in all its forms to secure legitimacy and, more importantly, money. By all appearances, his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, is tightening his control of the state and policy. This dynamic poses problems for the Kremlin’s most important relationship with a non-Western power.

Talk of Putin and Xi’s close personal relationship is largely a matter of PR messaging at a time when Russia needs China. Positive pronouncements do little to hide the difficulty both sides have in reaching real economic agreements in particular. Recent developments in the two countries’ energy ties and shifting personal power among those in and close to the Kremlin suggest that relations with China will continue to be warmer than ever on the surface, but ever more difficult to manage as the domestic political divergence between the two grows.

Evolving Energy Relations

Given the overly personalistic nature of Russia’s policymaking community, institutional gaps in knowledge pose serious risks. Russia’s elites suffer from what Carnegie Moscow’s Alexander Gabuev has diagnosed as a “near complete illiteracy” concerning China. State oil giant Rosneft has emerged as the country’s de facto leader for much of its China policy because of its importance in delivering the Kremlin necessary budget revenues. But Rosneft and its CEO Igor Sechin’s policy influence hit a big snag recently with news about CEFC China Energy, a key partner, and a shift in China’s institutional landscape.

Early last September, CEFC China Energy paid $9.1 billion to acquire 14.16 percent of Rosneft’s shares from Glencore and the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA). The purchase helped shore up Rosneft’s privatization deal from the previous December, which had run into various complications due to sanctions. Supply deals worth hundreds of millions of barrels of oil over the next five years have followed, as well as a deal making CEFC Rosneft’s primary oil trader in Asia.

But the head of CEFC, Ye Jianming, is now being investigated for economic crimes linked to a lack of transparency over CEFC’s debt and funding for various deals. In early March, Ye was reportedly detained for questioning.

The Shanghai Guosheng Group Co., a vehicle owned by the Shanghai city government, then seized operational control of CEFC. State-owned Huarong Asset Management Co. bought a 36.2 percent stake of CEFC and the state-run CITIC Group is looking at acquiring 49 percent of CEFC’s subsidiary for European operations. Last week, CEFC’s website announced that Ye was relinquishing his role in CEFC Europe.

Igor Sechin has a big problem on his hands: CEFC was privately owned and now state-owned Chinese firms are about to acquire stakes in Russia’s preeminent oil champion.

Though the state-private distinction is incredibly blurry and often irrelevant in both Russia and China, Sechin and his own network benefited from Ye’s assumed connections to China’s military-intelligence structures. That CEFC was expected to raise $5.1 billion in short-term loans from Russia’s VTB – a funding vehicle for projects the Kremlin prioritizes – evidenced substantial support in Moscow. These deals operated within the personalized style of economic politicking that Russia uses.

But on top of a new role for China’s state firms, Beijing is creating a new energy ministry to coordinate policy and oversee the country’s energy sector. The ministry would be distinct from the existing institutions governing oversight, a move that will give Xi and the state greater control over deal-making given the need for energy market reforms in China. Xi has also sought to distance himself from Ye and CEFC as its international profile has grown. That likely spells driving for harder bargains in future deals.

The news parallels China’s decision to not extend fresh loans to Nicolas Maduro’s government in Venezuela. China’s CNPC and Rosneft have both competed for control of production, forming a toehold in the Caribbean. Rosneft has extended $6.5 billion in loans to Caracas, though it claims that half that has been paid back. But without further loans from China, it will fall to Moscow and Rosneft to prevent a full collapse of Maduro’s regime once it needs more financing. Beijing is boxing them into a commitment that will cost billions — billions they need to spend elsewhere. Russia’s international presence elsewhere is likely to be increasingly linked to China’s oil diplomacy with Moscow.

The Kremlin’s Nuclear Family

Post-election trends within the Kremlin’s chaotic personalized policy apparatus will bear heavily on Sino-Russian relations. Shifting power centers among the Kremlin’s staff and appointees will create an increasingly challenging policy environment for Rosneft, Russian interests, and in some cases, China as well.

First Deputy Chief of Staff Sergei Kirienko’s star has been rising for some time, as he was handed the reins of Putin’s reelection campaign back in late 2016 as well as the task of replacing some of the Kremlin’s cadre without threatening stability. He succeeded in the former, with Putin winning a record number of votes in an election marred by less blatant vote-rigging than previous iterations. The latter is more complicated and implicates Kirienko himself, a figure considered a liberal within the Russian political system when he joined the administration.

Kirienko headed Russia’s nuclear giant Rosatom from 2007 to 2016 before joining Putin’s presidential administration and has retained a position heading the supervisory board overseeing it. His rise within the Kremlin has paralleled by that of the nuclear giant whose annual investment budget is rising 500 percent to match or exceed those of Rosneft and gas giant Gazprom by 2023. Nuclear power differs from oil and gas in that requires planning horizons that span the thousands of years spent fuel remains a threat. Rosatom is better run than Russia’s other state energy firms for that reason and Kirienko is enjoying the fruits of his labor.

Russia’s Northern Maritime Route through the Arctic has been given to Rosatom to manage, a flashpoint for future Sino-Russian cooperation in the Arctic. Rosatom managed to fight off Gazprom for the rights, likely aided by the support of Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin who is responsible for Russia’s defense industry and frequently spearheads military export diplomacy. The announcement was formalized after China issued its Arctic white paper in January claiming its role as a “near Arctic state.” That wedges Kirienko in Sechin’s way on the Russian side given the petty nature of fights over policy portfolios and makes him more important for future overtures from Beijing.

Rosatom has a China problem: Chinese state-owned enterprises are direct competitors for Rosatom in foreign markets. Recently, Rosatom is lining up against Chinese firms for deals in Saudi Arabia as China’s plans to triple its nuclear power generation in the next 20 years are causing a stir on international energy markets. As China’s industry grows, it’s likely that it will increasingly turn its gaze abroad. For that reason, Rosatom has signed international deals worth $133 billion as of January, 2017 and overall contracts worth $300 billion if they’re completed.

Unfortunately, Rosatom often runs into issues with its projects due to lack of financing, limits to how much technology it can export at once, and unprofitability. The company’s flagship Akkuyu power plant project in Turkey – a crucial element of Russia’s attempts to draw Ankara eastward – took a serious hit when Turkish investors pulled out in February. The project is slated to cost $20 billion. Rosatom prefers to maintain majority ownership in its internationald deals, often bearing too many costs.

China has an interesting role to play given the company’s piling obligations and dependency on Russia’s budget to get anything done abroad. China’s CNNC just invested 16 billion rubles into a uranium mine in Russia’s Zaibaikal region in exchange for a 49 percent stake in the venture with Rosatom and 600,000 tons of uranium a year. Rosatom also has some existing projects in China in cooperation with Chinese firms, but looks uneasy since China has managed to become largely self-sufficient for its technical needs. This has squeezed out space for Rosatom and its subsidiaries to profit off of China’s nuclear ambitions. The company will have to reach more deals giving up large stakes in lower-end projects like mining operations to Chinese firms if it wants to scrape together financing for bigger ticket items it earns relatively little on.

Mi Cadre

Kirienko’s policy portfolio is steadily expanding into oil. Having taken lead on vetting promotions and appointees for younger, up-and-coming technocrats filling important posts, Kirienko nabbed 32-year old Pavel Sorokin from the Ministry of Energy to oversee the oil and gas sector within the agency as Energy Minister Alexander Novak’s right-hand man. Sorokin has been involved in negotiating Russia’s production cuts with Saudi Arabia and OPEC. The move has not yet been finalized. The decision has been enforced top-down from the Kremlin against the interests and wishes of Russia’s oil companies. In doing so, Russian firms – namely Rosneft – are stuck doing their best to maintain a dominant position on China’s market while competitors in the U.S. and Saudi Aramco position themselves.

With Kirienko now running the Kremlin’s HR policy, in-fighting over energy diplomacy is bound to worsen in the coming years, particularly from Igor Sechin and Rosneft. Gazprom has largely been a peripheral player given it has yet to sell any piped gas to China, but that will most likely change by the end of 2019 though costs are rising rapidly.

China is now reorganizing many of its political and business structures that conduct or influence negotiations for deals just as Putin is forced to renew and update the policy and technocratic elites he surrounds himself with to maintain power. That process is invariably going to hurt Russia’s firms. Given Russia’s limited budgetary resources to shower them with patronage, they’ll likely be forced to sign onto more and more.

The costs of Russia’s standoff with the West continue to rise, with ongoing sanctions, the expulsion of Russian diplomats from several western countries, and growing discontent with the country’s negligent mismanagement. Though former finance minister Alexei Kudrin gives the Kremlin a two-year window to launch major reforms, Kirienko’s HR policy does not suggest anything big is in the offing. The CEO of Russia’s biggest private oil company, Lukoil, just announced plans to step down, likely tired of fighting off Igor Sechin as access to Russia’s budget is increasingly prized during leaner times. With all the quiet chaos beneath the surface, Beijing seems to be prepared to benefit.

Nicholas Trickett holds an M.A. in Eurasian studies through the European University at St. Petersburg with a focus on energy security and Russian foreign policy. He is a columnist and senior editor for the Foreign Policy Research Institute’s Bear Market Brief, acting Editor-in Chief for Global Risk Insights, and contributes to other outlets like Oilprice and Aspenia.