The Japanese government has been engaged in a delicate balancing act when it comes to Russia. Even as the crisis in East-West relations has intensified since 2014, Japan has strengthened political and economic ties with its northern neighbor. It has justified this policy as essential in order to secure a breakthrough in Japan’s longstanding territorial dispute over the Southern Kurils/Northern Territories. However, as geopolitical tensions reach Cold War levels, Japan is under increasing pressure to fall in line with its Western partners.

Among G7 members, Japan has been an outlier on Russia for several years. The first indication of this was in February 2014, when Prime Minister Shinzo Abe attended the opening ceremony of the Winter Olympics in Sochi, an event boycotted by major Western leaders. After Russia annexed Crimea the next month, Japan did introduce some sanctions, though these were designed to be extremely weak, thereby signaling the government’s reluctant adoption of the policy. Indeed, the identities of the 23 individuals sanctioned by Japan were never revealed.

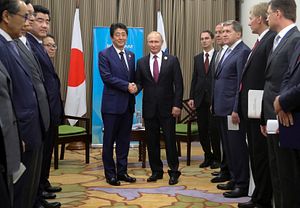

Rather than contributing to the international isolation of Russia, the Abe administration has pursued rapprochement. Most significantly, in May 2016, contrary to the advice of then-U.S. President Barack Obama, Abe returned to Sochi to meet with President Vladimir Putin. There, the Japanese leader announced a “new approach” to bilateral relations, featuring a commitment to high-level political dialogue and enhanced economic exchange, including an eight-point cooperation plan. Subsequently, the Japanese leader created the position of minister for economic cooperation with Russia, the only cabinet portfolio that explicitly names a foreign country.

The aim of this engagement is to lay the groundwork for a resolution to the countries’ territorial dispute, which has bedeviled relations since the contested islands were occupied by the Soviet Union in 1945. Japan’s official position remains to demand the return of all four islands, yet Abe, who recognizes this to be impossible at present, has instead focused on a more achievable interim goal.

Abe’s aim is to reach agreement on conducting joint economic activities on the disputed territory under a special legal framework that does not harm the sovereignty claims of either side. This would permit a significant Japanese presence to return to the islands for the first time in decades. It would also represent a legacy-defining foreign policy achievement that could be marked by a historic visit to the islands by the Japanese prime minister. Additionally, Abe hopes that a revival of Japanese influence on the territory could be just the first step toward its eventual return.

Agreement has already been reached on five priority projects and two joint survey visits were conducted in 2017. The remaining problem is the legal question, since Moscow is reluctant to permit Japanese entities to operate on the islands outside the framework of Russian law. On April 11, the second meeting of a bilateral working group, which was established to resolve this issue, concluded without apparent progress.

Despite this obstacle, Abe remains sanguine that a breakthrough can be achieved during his expected visit to Russia at the end of May. This trip is anticipated to include an appearance at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum on May 25, followed the next evening by attendance alongside Putin at the formal celebration of the Year of Japan-Russia at Moscow’s Bolshoi Theater. In demonstrating the increased closeness of both economic and political ties, this visit is intended as the culmination of Abe’s “new approach.”

Skripal, Syria, and the Intensifying Crisis Between the West and Russia

Abe’s carefully laid plans have been upset by two recent events. The first was the nerve agent attack on Russian former double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter in the United Kingdom on March 4. The second was the alleged use of chemical weapons by the Syrian military on April 7 in Eastern Ghouta. Each incident has deepened the sense of crisis between the West and Russia, placing Japan in an increasingly awkward position.

Following the Skripal poisoning, the British government was quick to assign blame, stating that only Russia has the “technical means, operational experience, and the motive” to carry out such an attack. Western countries supported this assessment and 28 states joined the U.K. in expelling Russian diplomats in retaliation; this even included the Russia-friendly government of Hungary’s Viktor Orban.

The Western response to the Syrian chemical weapons attack was even more emphatic, with the United States, France, and U.K. launching missile strikes on April 13. Western leaders also made it clear that they held Russia responsible for failing to prevent its Syrian ally from using chemical weapons. U.S. President Donald Trump, in particular, condemned Russia for being “partners with a Gas Killing Animal.”

In both cases, Japan sought to quietly distance itself from its Western partners for fear of antagonizing Russia. Within the G7, Japan was the only country not to expel Russian diplomats following the Skripal attack. What is more, despite being provided with the same intelligence as European states, the Abe administration refused to accuse Russia of involvement. On Syria too, Japan sought to avoid explicitly backing Western military action, saying merely that it supported the United States’ “resolve.”

Japan’s stance earned the praise of the Russian embassy in Tokyo, yet it began to attract increased domestic and international criticism. One particularly strident op-ed in the Nikkei accused Japan of failing to support its British “friend in need.” The article also compared Abe’s hopes of a territorial deal with Russia to the wishful thinking that prevailed before the end of World War II. At that time, while Japan was seeking Moscow’s help in mediating a negotiated end to the conflict, the Soviet Union was preparing to attack.

Falling in Line With the West

Ultimately, the Japanese government appears to have feared the threat of isolation within the G7. In advance of the meeting of the group’s foreign ministers in Toronto on April 22-24, Japan came under strong pressure and capitulated. It accepted a joint statement on the Skripal case that fully endorsed the United Kingdom’s claim that “it is highly likely that the Russian Federation was responsible for the attack and that there is no plausible alternative explanation.” Japan also added its signature to a separate statement that fully supported the U.S., France, and U.K.’s military strikes on Syria, describing them as “limited, proportionate, and necessary.”

This sudden change in posture leaves Japan’s carefully cultivated Russia policy in a state of confusion. Abe is still expected to visit Russia in May and the Japanese leadership will hope that Moscow takes the view that Japan was compelled to fall in line with the West. The optimistic Abe may even believe that Russia’s increased isolation may actually cause Moscow to place greater value on cooperation with Japan, thereby making progress on the territorial issue more likely.

The reality, however, is that Japan’s support for the G7 statements will have a negative impact on bilateral relations. The Russian ambassador in Tokyo stated that “It is truly sad to see Japan’s signature under these documents,” which he described as “the height of cynicism.” More broadly, the Russian side will conclude that Japan has limited autonomy when it comes to foreign policy and cannot be trusted to act independently. This makes it even more unlikely that Russia will agree to granting Japan’s request for a special legal framework on the disputed islands, since this will be regarded as making concessions to a adversarial neighbor in a sensitive border zone.

Overall, it seems unlikely that Abe, whose own star is fading, will achieve his long-held dream of a breakthrough in the territorial dispute with Russia. What is more, as divisions between the West and Russia reach Cold War depths, Japan’s ability to pursue an independent policy of rapprochement with Russia will be increasingly restricted.

James D. J. Brown is Associate Professor of Political Science at Temple University, Japan Campus.