“We saw each other as individuals rather than as an Indian or a Pakistani. I feel that it is similar to discriminating someone on the basis of their caste, creed and race, something that is not in their hands at all,” says Pritam, who strongly believes that one shouldn’t be discriminated against on the basis of their place of birth.

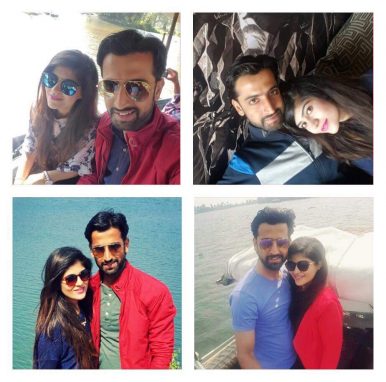

Pritam and Fiza (names changed), met each other while studying law at Oxford University in 2005 and got married in 2012. Even though in the eyes of society theirs is an inter-religious and cross culture marriage as Pritam is an Assamese Brahmin while Fiza is a Pakistani Punjabi Muslim, they do not consider such social constructs as barriers.

Fiza, who comes from a conservative family, says, “I informed my parents about Pritam after getting married. At that time we were in London and invited them to meet us. They stayed with us for three weeks and grew fond of Pritam, but never disclosed our marriage to our extended family because of the social pressure.”

Pritam and Fiza are of the very few courageous couples who together are fighting age-old rigid notions that place absurd restrictions on people.

Pritam and Fiza are concerned more for their 1-year-old daughter, who is too small to understand these social complexities. They fear that they might have to move to a neutral country despite their wishes to stay back and serve the land they belong to.

“It’s so funny that my friends who married a German or an Australian can get a PIO (Person of Indian Origin) card very easily for their spouses whereas Fiza cannot, when Pakistan is historically, culturally, socially, and geographically more connected to us,” says Pritam.

The division of India and Pakistan in 1947 uprooted millions of people and its shadows of hatred and divide still haunt the two nations. Since then, the relationship between them has been unfriendly and inhospitable. However, despite sour national relations, marriages between Indians and Pakistanis continue to take place.

These marriages defy the stereotypes created around “the other” country. For some couples, marriage in the neighboring country is an arranged setup. For others, love happens organically, and borders are just lines.

Naresh Tiwani tweeted to the Indian foreign minister for help getting visas for his then-fiance’s family to attend their wedding in November 2016. Photo provided by Naresh Tiwani.

Naresh Tiwani and Priya Bachini tied the knot on November 7, 2016 when tensions between the two countries were high. Priya and her family are from Karachi, Pakistan and were unable to get visas as the wedding date approached. Naresh tweeted his plight to then-Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj, who stepped in to help Priya and her family get visas.

“It was quite tiring for both the families because the wedding date was so near and the Indian embassy was not granting visas and still Priya is staying in India on a long term visa (LTV) and has not visited Pakistan after our marriage,” said Naresh.

Naresh and Priya belong to the Sodha community, which is known for having cross-border marriages as a part of their tradition. “There are certain clans on both sides of border who culturally don’t have options for marriages and thus they prefer to opt for cross-border marriages. Government should ensure friendly visa regime at least for such marriages and the process of giving citizenship to them should be liberal,” said Hindu Singh Sodha, founder of Seemant Lok Sanghatan, an NGO which strives to make the cross-border marriage process easier.

Some cross-border marriages also reflect cross-border family ties. Parveen Irshad, who got married to Irshad Mirza in 1981, says while sitting in their old Delhi house: “This is my Dada’s [grandfather’s] house. My husband is my cousin.”

Parveen came to visit her family in India, with no intentions of getting married. “My marriage was not planned. My parents felt Irshad to be a good partner for me and got us married.” She has been staying in India on a long term visa (LTV) since her marriage and cannot move out of Delhi.

Parveen Irshad, who married Irshad Mirza in 1981, sits in their old Delhi house. Photo by Ayesha Khan.

Parveen has been lucky to visit Pakistan once every two years since her marriage. “When I go to Pakistan, I visit places. Here in India I cannot, due to visa restrictions.”

Parveen’s elder daughter is also married to a Pakistani. “My daughter is a proud Indian and still holds her Indian passport. I feel India and Pakistan should allow people to hold dual citizenship as many families were divided during Partition and their children own their loyalties to both sides,” she says.

“The government of India provides citizenship to anyone who lives here for five years, but they have declared Pakistan as an enemy nation by law which is why Pakistanis face so many issues. The Pakistani spouses have to stay on long term visas for years and go through strict regular check ups,” explained Imran Ali, a lawyer and professor.

Regardless of the countless difficulties these couples wish for peace, prosperity and friendship between both countries and believe that marriages like theirs should continue to taking place to fight the politics of hate.

As Kabir, a poet revered in both nations, puts it:

“Hadd gayi anhadd gaya, raha Kabira hoye.

Behadi maidan mei, raha Kabira soye.”

(Crossing from bounds, boundless has become Kabir.

In the land of boundless, thus sleeps Kabir.)

Ayesha Khan and Tahira Noor are students of Convergent Journalism in Jamia Millia Islamia University.