The Mlabri are one of the smallest ethnic groups living in Thailand, numbering about 400 people.

In a period of about 20 years they made a transition from nomadic hunter-gatherer communities living in the forest to a sedentary lifestyle in permanent settlements. They experienced rapid social change when encountering the modern world.

Until the 1990s, the Mlabri lived a nomadic life mainly in forested areas. They lived in mobile units, staying in one place for about five to 10 days, and subsisted largely on hunting, gathering, and digging activities in the forest.

They had limited relations with other ethnic groups living in the mountains, but would sometimes exchange forest products for consumer items such as salt, steel, tobacco, clothes, pigs, rice etc. and occasionally were hired through exploitative, short-term labor arrangements in which they worked for food and clothing as laborers on the farms of Hmong and northern Thai living nearby.

Their traditional lifestyle continued until the 1970s but has gradually changed since then because of deforestation due to agricultural expansion, logging, and road construction.

Day labor became more important for survival as the natural resources that the Mlabri depended on decreased dramatically; the forest was exploited by lumber companies and by ethnic groups who engaged in swidden agriculture.

In the late 1990s, state-led initiatives introduced a sedentary lifestyle to the Mlabri, bringing them in places near already settled Hmong communities, and encouraging them to start cultivating their own rice and corn fields.

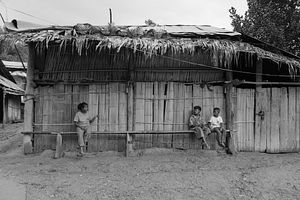

Today, they live in five permanent settlements in the Nan and Phrae provinces, engaging in wage labor, cash crop cultivation, and ethnic tourism.

Traditional hunting and gathering activities still continue, but on a minimal scale (about 7 percent of their food source) and are restricted by access to already rare and over-hunted forest areas, which are under the control of the Thai government.

In 2001, the Mlabri gained formal recognition through citizenship and ID cards with presumed birthdates for individuals born before 1998, and the actual registered birthdates for those born after. Citizenship provided them with access to health and nutritional services at government facilities and children started attending school. Authorities carried out different programs in education, public hygiene, and occupational training, including cultivating cash crops and livestock farming.

Traditional, animistic beliefs still remain, but new faiths and activities were also introduced through Christian and Buddhist missions.

Sascha Richter is a documentary photographer based in Berlin, Germany.