Xi Jinping has a global vision for China and has centralized foreign policy around himself and the CCP. In this six-part blog series, MERICS researchers take a closer look at the (new) setup of China’s foreign policy leadership, institutions, budget, and personnel – as well as on its policy approach to Europe. This is part 6; see part 1 of the series here.

In the run-up to the latest 16+1 Summit in Sofia in July 2018, China’s Prime Minister Li Keqiang went to great pains to explain that the regional cooperation format with 16 Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries was by no means intended to undermine the European Union (EU). “We have promoted 16+1 cooperation as part of the efforts to promote European integration. We welcome a united and prosperous Europe. We welcome a strong euro,” Li said at a news briefing with Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borissov.

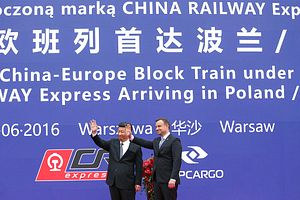

Li’s statement appears to confirm Beijing’s commitment to the integration of Europe. After all, China benefits from a common market for goods and services and it views Europe as one influential pole in the multipolar world order the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) would like to see emerge. However, deeds speak louder than words. Over the past two years, China’s infrastructure foreign policy in CEE countries, mainly through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and the related 16+1 format, have raised the question whether Beijing’s priorities in Europe have changed.

Infrastructure Projects Create Fiscal Instability in EU Neighborhood

China’s BRI-related infrastructure projects are creating fiscal instability in the EU’s regional neighborhood and often fail to align with EU rules and standards for building large-scale infrastructure, from transportation to energy and communications. The Bar-Boljare highway in Montenegro illustrates this point. The IMF warned that the project, which is financed by a Chinese loan, will drive the debt levels of the small country to unsustainable levels. Not only that, but the European Commission has noted a growing lack of appreciation for EU rules on public procurement and state aid, environmental impact assessments, and sound cost-benefit analyses. Brussels is also concerned that the significant resources invested in the project will create “other important transport bottlenecks and high maintenance needs.”

It is no coincidence that China has had a much harder time implementing the BRI inside EU borders. In February 2017, the European Commission opened a formal investigation into what is meant to become the flagship BRI construction project in the EU, the 2.45 billion euro ($2.8 billion) high-speed rail link between Belgrade in Serbia and Budapest in Hungary. Brussels not only expressed doubts about the financial viability of the rail line but also suggested that the project did not comply with EU public procurement rules. Budapest had failed to release a call for public tender normally required for projects of this magnitude. Eventually, at the November 2017 Budapest 16+1 Summit, an official call for tender for the project was issued. Neither bidders nor the winner have been announced so far, but the remarkably short timeline suggests that one of the tenderers might have had an inside track.

China has recently sought to address European concerns about its infrastructure foreign policy. This includes high-level promises to be more responsive to European connectivity priorities identified by the EU and its member states. Beijing has also encouraged Chinese policy banks to partner up with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and European development agencies in the implementation of BRI projects in Europe and its immediate neighborhood. However, this does not change the fact that the vast majority of BRI projects in the CEE region remain firmly in the hands of Chinese lenders and companies. Rather than waiting for concessions from China, the EU will have to stand up for its own interests and vision – be it with its upcoming connectivity strategy or with a more assertive NATO neighborhood policy.

China Charges Ahead With 16+1 Despite Concerns

The way China has positioned itself within the 16+1 framework is another critical indicator that Beijing’s Europe policy might have changed in fundamental ways. The initiative has recently lost momentum as many of the promised infrastructure and investment projects have been delayed or have failed to materialize, leading to disappointed expectations. In what was a clear snub to Beijing, at the July 2018 Sofia 16+1 summit, Poland — the biggest European 16+1 economy –was only represented by the deputy prime minister, while Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki attended a pilgrimage gathering at home.

At the same time, Beijing hardly seems to regret the divisive political effects of the 16+1. A growing number of senior Chinese political analysts openly admit that the point of the 16+1 was to find a new way of shaping EU politics when the EU was no longer as responsive to Chinese interests and concerns as the CCP would have liked to see. Since 2012, the 16+1 format has provided China with growing political influence in Central Europe – and arguably also Brussels – exacerbating tendencies toward greater fragmentation in Europe.

China has remained unimpressed by louder calls from Berlin, Brussels, and Paris recently to tone down its 16+1 activities. Rather, Beijing has sought an intensification and broader institutionalization of the format. It also welcomed the interest expressed by Austria and Greece, currently 16+1 observers, in full membership of the format. The fact that the Sofia 16+1 summit was moved forward by almost half a year from its original schedule on China’s initiative to only a few days before the EU-China summit this July left many EU officials irritated and even made some EU 16+1 members uncomfortable. Also, China has not given up on the idea of establishing additional subregional formats in Northern and Southern Europe.

It is too early to suggest with absolute certainty that all this indicates a fundamental shift in China’s European policy. The recent frictions with Brussels could have been the unintended result of a strategic miscalculation on Beijing’s part. But if Beijing does not adjust its policies in response to the current backlash in Europe, there is reason to assume that China’s previous emphasis on European cohesion has been replaced by the priority to strengthen China’s influence in different parts of Europe – no matter the political cost for the EU and its citizens.

Jan Weidenfeld is Head of the European China Policy Unit at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) in Berlin, Germany.