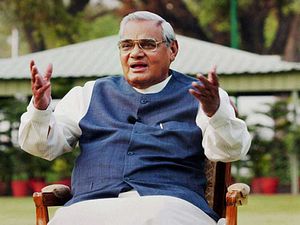

Atal Bihari Vajpayee, a former prime minister of India, died today. Born in 1924, his eventful life encompassed most of the modern history of his country: from the end of British rule to the entire post-independence period. India’s first prime minister from the now-dominant Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), he served as prime minister for 13 days in 1996, for 11 months between 1998-1999, and then for a full five year term between 1999-2004, becoming the first prime minister not from the Indian National Congress to serve a full term.

In his youth, Vajpayee was influenced by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a Hindu nationalist organization from which the BJP also draws its ideological roots. He was first elected to Parliament in 1957. He was subsequently re-elected 11 times, and “became a prominent critic of the governing Congress party. In 1975, he and thousands of other dissidents were jailed under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s emergency decrees suspending civil liberties and elections.” After the emergency ended, he served as foreign minister in a coalition government, India’s first non-Congress government, from 1977-1980. After Congress returned to power in 1980, he helped found the BJP.

His party’s — and his — rise to power were driven by the 1992 destruction of the Babri Masjid, a mosque in the city of Ayodhya, by a Hindu mob, because the mosque had ostensibly been built on the site of the Hindu deity Rama’s birth. In the riots that followed, Hindus and Muslims became increased polarized, and Congress seemed increasingly unable to represent the aspirations of India’s mostly Hindu middle class, people who were discovering both nationalism and capitalism. Moreover, after the birth of regional parties in the early 1990s and the assassination of two consecutive Congress leaders from the Nehru-Gandhi political dynasty in 1984 and 1991, India was ripe for a political paradigm shift.

Vajpayee’s skill lay in harnessing this energy to come to power and rule in a more moderate fashion, a path that has since been followed by India’s current prime minister, Narendra Modi, also from the BJP. Unlike many who were influenced by the RSS, Vajpayee ate meat and drank whisky. Despite his ideological roots, Vajpayee focused on improving India’s economy and international relations. He kept the RSS at an arm’s length, and in fact did not commit to building the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya, which was a primary demand of Hindu nationalists. Most famously, after the 2002 Gujarat Hindu-Muslim riots, which occurred while Modi was that state’s chief minister, Vajpayee advised Modi to follow “raj dharma” or the way of kings. Vajpayee stated at a press conference while seated next to Modi that “a ruler should not discriminate against the subjects. Not on the basis on birth, not on the basis of caste, not on the basis of religion.”

But Vajpayee still was a muscular nationalist and champion of realpolitik, in a mold that broke decisively with the recent past, and was instead inspired by the more distant past. Harkening back to the deeds of the Hindu kingdoms of old, and the ethos of the warriors of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, his style was firm, brave, powerful, but nonetheless, righteous. He felt that India needed a more robust government, modern but also rooted more closely in its traditions, in order to meet its potential.

He became the first prime minister to address the United Nations in Hindi, and risked the international community’s censure and sanctions to order nuclear tests in 1998, openly declaring India a nuclear power. He held firm against the Pakistani’s military incursion in Kargil, located in Kashmir in 1999. In 2001, in response to a terrorist attack by Pakistani-based militants on India’s parliament, he sent half a million troops to the border, although the situation was eventually de-escalated. However, he also tried to improve relations with the United States despite the imposition of sanctions after the 1998 nuclear tests, and with China, because he felt that this was in India’s long-term interests. Under him, India formally recognized that Tibet was a part of China, in exchange for Chinese recognition of India’s 1975 annexation of Sikkim.

Vajpayee’s tenure was the political expression of profound social and economic shifts within India that had previously remained unmanifest. While a predecessor of his from the Congress Party, P.V. Narasimha Rao (1991-1996), laid the groundwork of India’s economic opening and transformation away from the socialism championed by India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, and his daughter, Indira Gandhi, it was Vajpayee who forged economic growth, geopolitical realism, and Hindu nationalism into the winning ideology it is today. He implemented long overdue policies, neglected by previous governments, in order to improve India’s human development: primary education became free for the first time, and India launched major highway projects such as the Golden Quadrilateral Highway, connecting the four corners of the country.

Perhaps his policies did not go far enough in rural areas, and perhaps the Indian people were not yet ready for the developmental model that was later taken up by Narendra Modi. After all, even today, Indians often vote on the basis of caste, clan, language, and religion. The BJP unexpectedly lost its re-election bid to Congress in 2004, and Vajpayee retired in 2005. But he laid the foundation of India’s transition to a global economic and strategic power, and of its interpretation of its nationalism from being defined by the struggle against colonialism, to one inspired by memories of India’s ancient past.