ULAANBAATAR — When Sodnomsengee Ulziitogtork, 42, returned home to Mongolia after spending several years working as a construction laborer in South Korea, the first thing that caught his attention was the lack of parks and public spaces in his home country.

“In Korea, there are many parks and children play in safe, clean, beautiful areas,” Ulziitogtork, who is locally known by the nickname “Ulzii,” said. “I came back to Ulaanbaatar and saw that children didn’t have parks. Instead, they were playing around rubbish. It broke my heart.”

Ulziitogtork is compassionately considered an eccentric in his community — a man of big and bold ideas that some might find unconceivable. He resides in the northern outskirts of Ulaanbaatar, surrounded by the informal yurt dwellings known as gers. The Mongolian capital’s ger districts are often homes to some of the most impoverished communities in the city, if not the country.

Sodnomsengee Ulziitogtork, 42, spent several years working as a construction laborer in South Korea,. When he returned to Mongolia, he noted the lack of parks for children. Photo by Didem Tali.

Climate change in Mongolia has manifested as harsher winters, causing a natural disaster known as dzud, in which a large number of animals starve or freeze to death. In 2018 alone, dzud killed 700,000 livestock animals, making it impossible for thousands of traditional nomadic families to survive in the countryside.

Due to dzuds, a rising number of formerly nomadic families have moved to the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar to live in gers, as they cannot afford modern apartments. There are currently over 800,000 people living in the ger districts in Ulaanbaatar, a city of 1.3 million, which is also the world’s coldest capital. Temperatures can drop to as low as minus 40 degrees Celsius in winter. These urban poor communities often lack access to many basic services and breathe some of the world’s most polluted air as they burn cheap coal to deal with the harsh winter conditions.

According to Enkhnasan Nasan-Ulzii, chief of social policy at UNICEF Mongolia, infrastructural challenges and pollution in ger districts cast a dark shadow over the childhood experience for the urban poor families in Ulaanbaatar.

“Child poverty is significantly overrepresented in ger communities,” Nasan-Ulzii said, explaining that by UNICEF’s estimates approximately 140,000 children live in poverty. “Ger districts aren’t great places to be a child and they are disconnected from the central systems. There are no facilities or infrastructure for a healthy childhood.”

Rachel Machefsky, an early childhood development specialist at Bernard Van Leer Foundation, says pollution is a “silent killer” for children. The physical trauma of exposure to pollution can severely hinder their development and brain health.

“Children are much more vulnerable to all types of pollution,” she said. “Playing in polluted places can expose children to potentially lethal bacteria and illnesses.”

“They also breathe faster and have smaller, shorter bodies, which means they take in much more of the polluted air than adults,” Machefsky added. She said that lack of clean and safe play areas during childhood can continue to follow children for decades in the form of poorer economic prospects due to missed school days and developmental delays, chronic diseases, and even lower IQs.

Living among thousands of poor children, one day in 2011, as Ulziitogtork was walking in his neighborhood, he came across a particularly upsetting sight.

There was a former granite mine in his neighborhood, which according to Ulziitogtork the Mongolian government used to build modern Ulaanbaatar in the 1940s, exploiting the labor of Japanese war prisoners.

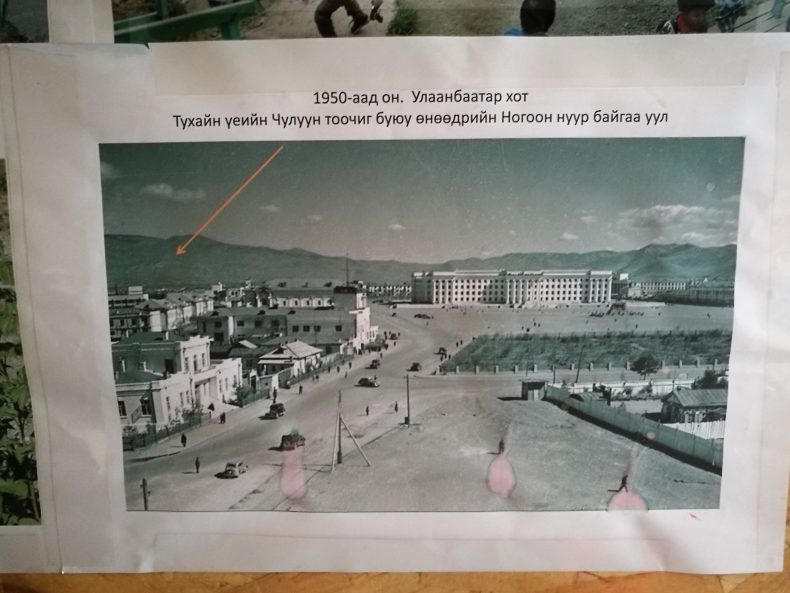

In this photo of Ulaanbaatar in the 1950s, an arrow points at the location of the former granite mine, which is now the park.

The Mongolian capital acquired formidable granite squares, statues, and buildings thanks to the stones extracted from mines in northern Ulaanbaatar. After a peace agreement between countries, Japanese war prisoners who survived the difficult conditions in Mongolia were sent back home in the late 1940s. With time, mining activity gradually stopped and all that was left of a mine that helped to build modern Ulaanbaatar was an empty ditch.

However, as the ger district became more crowded with people migrating to the city’s outskirts from the countryside every year, many households didn’t have access to waste management networks. The ditch gradually filled with rubbish.

“It wasn’t an officially designated landfill,” Ulziitogtork said. “But people didn’t have anywhere else to dispose their waste. So [the former granite mine] was full of rubbish and children were playing there.”

The ditch that was formerly a unofficial landfill was cleared by one man on a quest to given local children a real place to play. Photo by Didem Tali.

When Ulziitogtork saw children in the mine-turned-landfill, he had an epiphany: During his years as a construction laborer in South Korea, he had saved some money and acquired exactly the right skills to help his community. After he came back home, he built an apartment building, which gave him some rental income. This meant that Ulziitogtork wasn’t in a bad place financially for a ger district-dweller and he realized he could help his neighborhood’s children.

He decided to clean the unofficial landfill, and then turn it into a beautiful park — like the ones he had seen in South Korea. He would use his own savings to do this and consider it a gift to the children of his community.

Feeling energized by this plan, Ulziitogtork immediately got to work. He first cleared out 300 bags of trash, each of which, he estimates, weighed around 60 to 70 kilograms (132 to 154 pounds). Once all the rubbish was cleared out, he found a nice surprise from nature: Rainwater had collected in the bottom of the ditch that was dug by the miners. This meant there was a small artificial lake which had remained hidden for decades under the rubbish.

In this photo, children play in the small lake at the bottom what was once an unofficial landfill. Photo by Didem Tali.

It took Ulziitogtork two years to clear the landfill and construct a children’s park surrounding the small lake. Nowadays, the small lake that he discovered harbors small boats in summers and functions as an ice skating rink in winters. It’s still a work-in-progress: He keeps tweaking the park with new ideas and plans.

The park also acts as a community and learning center for children. There, they can participate in ice skating activities, watch open-air cinema over the small lake in summers, and learn about Mongolian culture.

After Ulziitogtork’s efforts, the local government not only gifted him the permanent rights to use the former granite mine, but they also honored him with an award for his services to the community.

Ulziitogtork has had a lifelong passion for cinema, arts, and culture, despite no formal training and having been a blue collar worker most of his life. He also dabbles in filmmaking and hopes to screen more films and host filmmaking workshops in the future. The park currently serves 6,000 children in the area. The children keep coming back for various activities, as Ulziitogtork keeps working on transforming his park into a better community and cultural center every year.

The park was empty in this photo, as the children were all in school, but it comes alive after schools gets out. A lake in the summer and an ice rink in the winter, there’s always something for children to do at the park. Photo by Didem Tali.

Nasan-Ulzii of UNICEF says community centers for children are key elements in ger districts to improve children’s lives and healths. However, she warns that exposure to air pollution in the winter can still have devastating health consequences for young children.

“There is no escape from pollution and bad infrastructure for children,” she adds. Unless the government finds a holistic solution to fight these issues in a long-term and sustainable way, Nasan-Ulzii fears that pollution will continue to devastate the lives of thousands of poor children in the ger districts of Ulaanbaatar.

Nevertheless, Ulziitogtork is determined to keep improving his park and he finds fulfillment in putting a smile on 6,000 faces every year. Even though he is also worried about the pollution, he keeps an optimistic attitude for change. The joyful squeals of children that he hears in a former landfill that used to exploit war prisoners is proof of change and a testament to the future’s possibilities.

Didem Tali is a multimedia journalist covering global economy, gender, environment and displacement issues from around the world.