“Nobody worries about climate politics anymore; all attention is on the political climate,” a Chinese climate observer recently on posted on Chinese social media. Indeed, with punitive tariffs dominating the headline, the mood from the Obama-Xi climate honeymoon is certainly long gone. These days, Beijing’s policy community is kept busy second-guessing the U.S. president’s next trade move. Increasingly, they worry that the trade tension is merely part of a broader strategy of containing China.

The trade war is shifting Beijing’s perception of the West as well as its own position in the world. Barely a year has passed since President Xi Jinping proudly declared his vision for China to be a “participant, contributor, and leader” in global environmental affairs. Now confidence is waning. With its rapid rise directly confronted by the most powerful nation in the world, the mood in Beijing is bleak.

Views in the climate change community are divided. The progressive side advocates for keeping a high-profile climate agenda. This school of thought believes the changing geopolitics provides not only an opportunity for Xi to become the champion of multilateralism, but also brings home the urgency of doubling down on the reform agenda. To these progressives, the current tension between China and the West is a reflection and escalation of the West’s frustration over China’s stalled economic reform. While China is currently pressed to advance primarily over issues such as trade, investment, and intellectual property rights, that is all the more reason to prevent a climate retreat. After all, climate has been the poster child of the country’s pursuit of becoming a responsible global citizen.

The other side of the aisle is much less gung-ho. For the conservatives, engagement and commitment are only meaningful when the United States is at the table. To them, at a time when President Donald Trump is pulling his country out of major international agreements, lecturing China to play by the rulebook is nothing but a disingenuous talking point — part of a broader strategy of curtailing China’s growth. Instead of being the torch bearer, these conservatives argue, Xi should quietly put his own country first.

Such are the two climate policy camps that are taking shape under the fractious relationship between China and the West. Dangerously, there is not much in between them, and the progressive side risks slowly losing momentum as diplomatic tension takes a heavier toll on the previously upbeat foreign policy strategy.

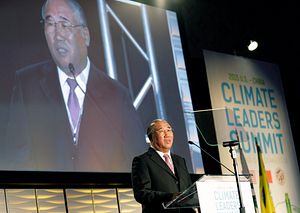

The months in the run up to the 2019 UN Secretary-General’s Climate Summit, a head of state level gathering where the UN is asking leaders to present higher ambition, will see Xi carefully contemplating these two polar opposite views.

Facing unprecedented international troubles and daunting domestic challenges, China seems to be a wary giant on the global stage — its rapid growth benefited tremendously from the international system established by the West, yet in the absence of strong leadership from Washington, Beijing is not convinced about footing the bill by itself. The result is a country that has already waved goodbye to the old, but is not quite ready to embrace the new.

The resistance against taking a larger role are displayed vividly in two recent events.

At the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), a triennial bilateral summit held in Beijing and attended by 53 African leaders in early September, Xi unveiled a $60 billion financial package in support of African development. The announcement immediately set a fire on Chinese social media, invoking public disapproval of the extravagant spending while unleashing long-accumulated frustrations over other socioeconomic issues. This highlighted the potential domestic opposition at the grassroots level to an internationalist diplomatic approach. There is reason to believe that the pushback at the elite level will be no less fierce, particularly when it comes to issues involving profound economic interests such as climate change.

Around the same time and across the Pacific, China’s veteran climate chief Xie Zhenhua spearheaded a large Chinese delegation at the Global Climate Action Summit (GCAS) in San Francisco. At the birthplace of the idea of non-state climate action, the Chinese demonstrated they learn and adapt fast — Chinese local officials, business executives, academicians, philanthropists, and NGOs were all galvanized, and ready to put resources toward not just domestic environmental issues, but global action. Xie’s message to the world was clear: China is ready to engage, contribute, and lead, at all levels. In the absence of federal climate action in the United States, Xie was translating Xi’s grand vision into concrete terms in a manner that was cooperative with his U.S. subnational host.

While the leaders in Zhongnanhai may eventually need to balance the internationalist and nationalist sides of China’s diplomatic discourse, their determination to maintain economic growth is strong and clear — even if it comes at the expense of environmental policies. As the country enters into winter heating season, a previously proposed blanket ban on steel and cement productions was considerably weakened in the face of industrial complains. Meanwhile, as the government grapples with slower economic growth, the Environmental Ministry’s seasonal PM2.5 reduction target for the upcoming winter was lowered from 5 percent to 3 percent.

Dark clouds are ahead. The calm and stable domestic and international environment that enabled China’s economic miracle is long behind. Over the last years, Beijing’s policymakers have proved their desire to be a climate leader when the political “weather” was good. Heading into increasing geopolitical tensions, the true test of their motive comes now.

Li Shuo is a climate policy advisor at Greenpeace East Asia.