In the first week of December, Sri Lanka’s political crisis deepened after the country’s Court of Appeal issued an interim order restraining former President Mahinda Rajapaksa from functioning as the prime minister. The interim injunction order, issued on December 4, also restrained 49 others from functioning as ministers. Technically, Sri Lanka is left with no functioning prime minister or a cabinet. The political uncertainty seems set to continue until the Supreme Court delivers the final verdict regarding the validity of the action taken by President Maithripala Sirisena to dissolve the Parliament.

The Court of Appeal issued its interim order in response to a Writ of Quo Warranto filed against Rajapaksa and others, stating that a no-confidence motion was passed by the majority in the Parliament against Rajapaksa holding the office of prime minister. However, Rajapaksa, responding to the interim order, filled appeals in the Supreme Court the very next day. He also claimed that he is not in agreement with the order issued by the Court of Appeal and insisted that only the Supreme Court is vested with the power to interpret the constitution and make final determinations on that regard.

Over the last month, Sri Lankan politics has been more dramatic than popular Netflix TV show “House of Cards,” with surprising events following in quick succession. Within a period of six weeks, a new prime minister and a cabinet were appointed, Parliament was prorogued and dissolved, the dissolution of Parliament was suspended by courts, a no-confidence motion was passed against newly appointed prime minister, and finally the Court of Appeal has restrained the newly appointed prime minister and cabinet from functioning.

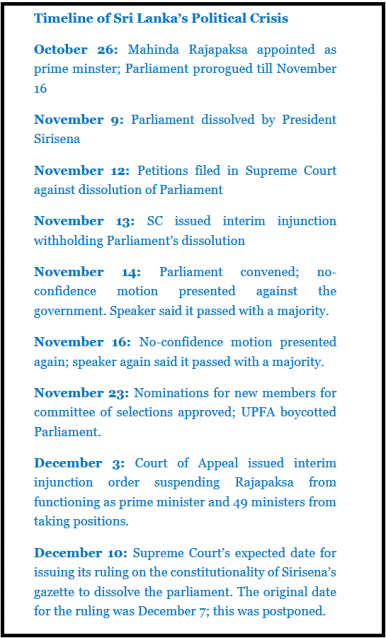

Political turmoil in Sri Lanka started on October 26, when the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA) handed over a letter to the speaker, Karu Jayasuriya, stating that they would withdraw from the coalition government formed with the other major party of the country, the United National Party (UNP). A few hours later, former president and current MP Mahinda Rajapaksa was tapped as the prime minister by Sirisena, who had defeated Rajapaksa in 2015 presidential election with the support of the UNP.

Despite this shock appointment, ousted Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe refused to leave the official residence of the prime minister, claiming that he has the parliamentary majority. He insisted that the president convene a parliament session to allow MPs to vote and show who has the confidence of Parliament to hold the post of prime minister However, Sirisena prorogued Parliament till November 16, exercising his executive powers. During this interregnum, both parties were claiming that they have a parliamentary majority and MPs’ loyalties were shifting. Some MPs claimed that there were attempts to bribe them with money and cabinet portfolios.

While this saga continued, Sirisena managed to surprise the nation again on a Friday night. In another unexpected move, he issued a gazette dissolving Parliament on November 9. This move was severely criticized not only by the UNP, but also by the international community, claiming that the move was unconstitutional. Questions were raised whether the president has powers to dissolve Parliament after the introduction of the 19th Amendment to the constitution in 2015. The UNP and several other parties filed a petition in the Supreme Court challenging the dissolution. After considering these petitions, the Supreme Court suspended Sirisena’s order to dissolve Parliament till December 7, when the court planned to deliver a final verdict regarding the constitutionality of Sirisena’s move to dissolve parliament.  However, the Supreme Court did not issue the final verdict on December 7; instead the injunction order was extended till the final verdict is issued.

However, the Supreme Court did not issue the final verdict on December 7; instead the injunction order was extended till the final verdict is issued.

After the Supreme Court suspended the dissolution, Parliament was convened on November 14. At that time the UNP presented a no-confidence motion against appointed newly appointed Prime Minister Rajapaksa with the signature of 120 plus MPs (which amounts to a simple majority of the parliament, which consists of 225 MPs). Twice the no-confidence motion was discussed and votes were taken in the parliament even while fights were going on inside the chamber. Although the speaker informed the parliament that Rajapaksa was defeated by the no-confidence motion, Rajapaksa and the MPs who support him claimed that the speaker violated standing orders in the proceeding and they cannot accept the results of the no-confidence motion. Sirisena claimed that to decide about a no-confidence motion against the government, he wanted a name call or electronic vote, rather than a voice vote as done originally. On November 23, a vote was taken electronically regarding the nominations for the parliamentary committee of selection and was passed with 121 MPs voting in favor; UPFA members boycotted the vote claiming that the speaker violated standing orders.

Even then Sirisena does not seem to be convinced about the fact that a majority of the MPs do not have confidence in the newly appointed prime minister. Sirisena seems to be enjoying the same executive powers he previously voted in to get rid of after being elected.

Executive Presidency and Sri Lankan Politics

Ever since the introduction of the executive presidency to Sri Lanka, it has given immunity and much power to the president, including powers to prorogue and dissolve parliament. This has made it very difficult to have a president and government from two different parties. Such instances have often created political instability as the president has sufficient powers to intervene with the work of the government — including ending its term. Recently ousted Prime Minister Wickremesinghe has been a victim of executive presidential powers twice. Before Sirisena ousted him recently, Wickremesinghe experienced very similar consequences when he held the office of prime minister in 2004. Then-President Chandrika Bandaranaike exercised her executive powers and dissolved Parliament in February 2004. Three months prior to the dissolution of Parliament, Bandaranaike took over three minister portfolios, including that of defense minister, and Parliament to to delay the Wickremesinghe government from passing its budget.

When Bandaranaike took over three ministries in late 2003, the prime minister was completely unaware of it. In fact, Wickremesinghe was in Washington to meet with then-U.S. President George W. Bush. Wickremesinghe, when queried by the media in the United States about the sudden political change, said that things were all right when he left and claimed that he had a majority in Parliament. However, Wickremesinghe having a parliamentary majority didn’t matter much. Bandaranaike dissolved Parliament and called parliamentary elections in 2004 even before Wickremesinghe’s government completed three years in office. Wickremesinghe conceded defeat and Mahinda Rajapaksa was appointed prime minister.

The post of the executive presidency was vested with much power in Sri Lanka and all successive presidents utilized it whenever they could use it to hold on to power. Late President J.R. Jayawardene called a referendum in 1982 to extend the term of the Parliament instead of holding a parliamentary election to retain the five-sixths majority in the legislature. Late President R. Premadasa used executive powers to avoid an impeachment motion against him by proroguing Parliament. Bandaranaike, as outlined above, used executive power to oust the prime minister from a rival party and form a government headed by her party. Rajapaksa used it to gain a parliamentary majority by offering minister portfolios to MPs and further increased the power of an executive president. These crucial, sometimes dangerous, overuses of executive powers included the power to dissolve parliament after the completion of just one year of the term, powers to take over any cabinet ministry whenever the president wishes, and the power to appoint as prime minister anyone whom the president thinks has the confidence of Parliament.

However, as per the 1978 constitution, a president could hold office only twice. The very first executive president in Sri Lanka, J.R. Jayewardene, had to leave the presidency after serving for two terms. So did Bandaranaike who left the presidency in 2005 after serving twice. Yet, Rajapaksa wasn’t ready to go after serving two terms. He introduced the 18th Amendment to the constitution and removed the barrier to contesting elections for the third time. However, his bid for a third term ended up as a failed mission as he conceded defeat to Sirisena in the 2015 election.

The 19th Amendment: Reducing the Powers of the President

The consistent use of executive powers by successive presidents in order to hold on to power has somewhat demonized the executive presidency. Such events created a resistance against the executive presidency among the general public. Subsequent to the removal of term limits for the presidency in 2010 by Rajapaksa and some alleged interventions by the president to the top judiciary appointments created a strong sentiment among the public about the need to abolish the executive presidency. In order to do that, a common candidate was put forward by the opposition then led by the UNP. Sirisena, who had been the health minister under Rajapaksa and the secretary of the major party of the powerful Rajapaksa government left his positions and contested against Rajapaksa as the common candidate in 2015. One of the main campaigning points of the anti-Rajapaksa faction during the 2015 election was a pledge to take away the excessive powers vested to the executive president. In fact, Sirisena, who has seemed to enjoy his executive powers throughout the last six weeks, claimed that he was becoming president to defeat Rajapaksa and abolish the executive presidency. Although this was not a novel promise (Bandaranaike also pledged to abolish the executive presidency when she campaigned for the presidency in 1994; so did Rajapaksa in 2005), people believed in it.

Although Rajapaksa was defeated, removing the powers of the executive president was not easy. Removing certain powers required approval in a referendum. On that backdrop, the 19th Amendment was introduced in order to reduce powers of the president, as an amendment which doesn’t require approval in a referendum. This was passed with a large parliamentary majority in 2015. Changes introduced through this amendment included reducing presidential and parliamentary terms to five years, establishing constitutional councils, and preventing the president from dissolving Parliament before Parliament completes four-and-a-half years of its term. According to the architects of the 19th Amendment, due to the introduction of this amendment, Sirisena does not have powers to dissolve Parliament — a luxury enjoyed by other presidents and utilized by former President Bandaranaike — as it has not completed four-and-a-half years of its term. As per the 19th Amendment, an dissolution of Parliament before the four-and-half-year benchmark requires a two-thirds majority vote in the Parliament.

However, local media reported that Sirisena was informed by his legal advisers that there were issues in the way the 19th Amendment received parliament approval and therefore Sirisena still has powers to dissolve Parliament after it completes a term of one year.

What Next?

At the moment, the pending Supreme Court decision regarding the constitutionality holds the key. The decision, which is now due by December 10, will determine whether there will be a parliamentary election in the near future or not. At the moment, as per the law, the country does not have a functioning prime minister and a cabinet. The level of uncertainty seems to be beyond anyone’s imagination — especially when Sirisena claims that he will not reappoint Ranil Wickremesinghe as the prime minister even if every MP votes in favor of Wickremesinghe. In same speech on December 5, Sirisena blamed for the difficulties and stressed that he will take actions to resolve the country’s political crisis within a weeks’ time.

The expectation is that the Supreme Court will deliver its final verdict regarding the constitutionality of the dissolution of parliament before December 14. Sri Lankans will hope that at least the Supreme Court decision will bring this drawn-out crisis to an end.

Umesh Moramudali is a Sri Lankan journalist who is currently pursuing a Masters in Economics at the University of Warwick, U.K.