The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) also known as TPP-11 entered force on Sunday, December 30, 2018 ushering in a new set of trade rules for the Asia-Pacific region, which accounts for over 15 percent of global trade and 500 million consumers. The agreement establishes new rules for trade, specifically in the areas of intellectual property rights and e-commerce that will benefit both large and small firms, assisting with access to important information needed to do business and comply with its rules.

Included in the deal is a new set of sanitary and phytosanitary standards that establish a comprehensive and clear set of guidelines. Technical barriers to trade will be easier for member countries to manage because of the transparency in crafting these new trade rules. The agreement is truly a high watermark in the world of multilateral trade in the midst of failed WTO talks, the irrelevance of the G8 and the collapse of U.S. leadership in the arena of global trade.

Final negotiations to conclude and sign the agreement which includes the 11 original countries minus the United States occurred in October 2017. The agreement includes major tariff reductions among the first six countries that have ratified the trade pact so far (Singapore, Japan, Australia, Canada, Mexico and New Zealand). The last five of the 11 countries are still in the midst of their domestic ratification process and will likely complete it within the next 60 days. The agreement will next enter force, for Vietnam on January 14.

One aspect of the agreement that will have the most power to shift trade is in the area of tariff reductions. The decrease in tariffs for several key agricultural products will also limit the competitiveness of important U.S. exports. These include exports such as beef, pork and wine, that have had a strong presence in the Japanese consumer market.

Pacific Trade Norms Create High Water Mark

The trade agreement establishes a number of important provisions that will see further integration among the Asian and Pacific countries that are signatories, this number may expand within the year as Colombia, Indonesia, South Korea, Thailand and the United Kingdom have expressed interest in being included. Ministers will meet on January 19 to discuss expanding the agreement to these countries. The agreement is viewed as a benchmark for future trade agreements because of its comprehensive interlinked nature. Even goods viewed as “off limits” in other agreements are included, there is a tariff line for every single good and most are tariff free either as the treaty enters force or over time. The Asia Trade Center calls it “the most important trade agreement in 20 years” for good reason – no other trade agreement accomplishes what TPP11 does.

The revised CPTPP covers all but 22 of the original provisions of the TPP negotiations begun under President Obama’s term. By far the most important aspects of the deal govern how goods will be given access to member countries markets in two ways: the first is through import restrictions (that limit quantities of goods coming into a country); the second is through import taxes (which increase the price of outside goods for consumers).

Big Losses for U.S. Beef

The United States is likely to see significant losses from its decision to walk away from the agreement, especially in its important beef market. The United States ships over 40 percent of all of its exported beef to Japan (over $1 billion), it is viewed as an essential market. The U.S. Meat Export Federation estimates that the U.S. share of Japan’s beef imports will decline from 43 percent to 36 percent by 2023 and to 30 percent by 2028. Annual export losses could reach $550 million by 2023, and will exceed $1.2 billion by 2028. The increased access to Japan’s beef market for Japan’s Pacific trade partners is higher than any previous free trade agreement, including any agreement with the United States.

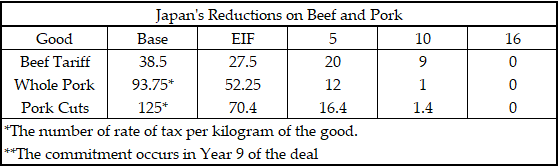

Although the higher tax on beef will remain in place for the United States (at 38.5 percent), Japan has committed to opening their market to beef substantially in the first year of the agreement or EIF (as it enters into force in treaty document language). Members of the Pacific trade deal will be taxed at a lower rate of 27.5 percent in Year 1, by Year 9 the tariff decreases to 9 percent. These decreases are already translating to savings for consumers as shops such as the mall chain superstore AEON have slashed prices on Australian beef.

Australia and Canada are both expected to benefit significantly from the revised TPP agreement, their access to Japan’s beef consumers is already increasing as prices decrease for consumers. New Zealand is another country whose beef exports are likely to benefit, the agreement will make their tariff rate the same as Australia’s.

Expanding Trade with Europe

The Pacific trade deal is just the first step in an expanding set of free trade agreements in the region for Japan, the trade agreement it reached with European countries will enter force on February 1, striking another blow to U.S. industries. Prior to Japan’s deal with Europe, the U.S. competed against both Europe and Canada for Japanese pork consumers. Europe will gain preferential access under the new agreement, and Canada will get similar access through the 11-member agreement.

U.S. pork producers are expected to lose more than $600 by 2023 as a result of its lower share of Japan’s market, this could increase to as much as a billion by 2028. These are significant losses. Japan is the most important market for U.S. pork, these exports are valued at 1.6 billion and account for a quarter of the global pork sales. As the table below illustrates, Japan will lower the tariff rate for whole pork and cuts of pork for its Pacific trade partners as it Enters into Force, by the 10th year most goods will have less than 2 percent tariff rate and will have no tariff by year 16.

Along with losses to Japan’s pork and beef markets, U.S. wine producers may also see a significant drop in their access to Japan’s consumers as a result of the agreement with Europe and the Pacific trade deal. Australia, Chile and New Zealand are touting the benefits both agreements will have for their wine producers. These nations will now compete with Europe as preferential players in Asian countries that are part of the deal, including Japan and Vietnam.

The value of U.S. wine exports to Japan average at about 35 million per year, the fifth largest export market according to Statista. The importance of Asia for U.S. wine is underscored by the Wine Institute, which on its webpage, urges the “U.S. government to begin bilateral discussions with Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia and other countries outside of the Pacific region to grow U.S. wine exports.” These are Asian economies where wine consumption is on the rise, but without an agreement in place, the United States will lose out to its competitors from Europe, Australia, Latin America and New Zealand.

Protecting Japan’s Sacred’s

According to the Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture Fisheries and Forestry, or MAFF, Japan’s agricultural industry will not be exposed to substantial competition from imports. The agriculture policy sector has considered sacred Japan’s domestic beef and pork, rice, wheat and dairy. On its webpage which answers frequently asked questions about the agreement, the Ministry states that only 20 percent of all agricultural, fishery and forestry products will be affected by the agreement and the sacred five products will not be threatened by the terms of the agreement at all. The webpage notes that the agreement will demand changes in only 1 percent of those products considered “sacred.”

In side negotiations with both Canada and Australia, Japan agreed to allow imports of rice and wheat beyond its commitment for these countries. Japan’s import of rice from Australia is set at 6,000 in Year 1 and then reach their highest level in Year 13 at 8,400 metric tons. These numbers are significantly lower than the goal of 215,000 that the United States was pushing for in earlier negotiations. Wheat imports are also similar capped in in Year 9, for Australia and Canada at 50,000 and 53,000 respectively. Along with limiting imports of wheat, Japan retains its ability to tax imports. Wheat from the Australia and Canada is taxed in Year 1 at 16 percent and decreases to 9 percent in Year 9 and each subsequent year.

These commitments, while meaningful, still allow Japan the ability to preserve its control over some of its sacred products by limiting the amount of goods imported if the country is overwhelmed by a surge of imports that harm domestic producers. The MAFF will be able to store rice and to use government purchase of domestic rice equal to the amount imported to maintain control over its supply as a staple food crop. This control over the supply of rice by government purchase basically means the MAFF preserves its control over the price of rice.

Nicole L. Freiner is Associate Professor of Political Science at Bryant University, USA. She is the author of “Rice and Agricultural Policies in Japan: The Loss of a Traditional Lifestyle” (2018) and “The Social and Gender Politics of Confucianism: Women and the Japanese State” (2012) both published by Palgrave MacMillan, as well as numerous articles on the state and civil society in Japan focusing on agriculture and environmental policy. She teaches courses on Comparative, Environmental and Global Politics and holds a Ph.D. from Colorado State University.