Some of the fiercest Muslim rebel commanders in the southern Philippines were sworn in Friday as administrators of a new Muslim autonomous region in a delicate milestone to settle one of Asia’s longest-raging rebellions.

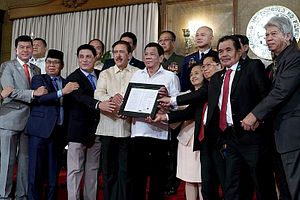

President Rodrigo Duterte led a ceremony to name Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) leader Murad Ebrahim and some of his top commanders as among 80 administrators of a transition government for the five-province region called Bangsamoro.

About 12,000 combatants with thousands of firearms are to be demobilized starting this year under the peace deal. Thousands of other guerrillas would disarm if agreements under the deal would be followed, including providing the insurgents with livelihood to help them return to normal life.

“We would like to see an end of the violence,” Duterte said. “After all, we go to war and shoot each other counting our victories not by the progress or development of the place but by the dead bodies that were strewn around during the violent years.”

About 150,000 people have died in the conflict over several decades and stunted development in the resource-rich region that is the country’s poorest. Duterte promised adequate resources, a daunting problem in the past.

The Philippine and Western governments and the guerrillas see an effective Muslim autonomy as an antidote to nearly half a century of Muslim secessionist violence, which the Islamic State group could exploit to gain a foothold.

“The dream that we have fought for is now happening and there’s no more reason for us to carry our guns and continue the war,” rebel forces spokesman Von Al Haq told The Associated Press in an interview ahead of the ceremony.

Several commanders long wanted for deadly attacks were given safety passes to be able to travel to Manila and join the ceremony, including Abdullah Macapaar, who uses the nom de guerre Commander Bravo, Al Haq said. Known for his fiery rhetoric while wearing his camouflage uniform and brandishing his assault rifle and grenades, Macapaar will be one of the 41 regional administrators from the Muslim rebel front.

Duterte would pick his representatives to fill the rest of the Bangsamoro Transition Authority, which will also act as a regional parliament with Murad as the chief minister until regular officials are elected in 2022.

Members of another Muslim rebel group, the Moro National Liberation Front, which signed a 1996 autonomy deal that has largely been seen as a failure, would also be given seats in the autonomous government.

Disgruntled fighters of the Moro National Liberation Front broke off and formed new armed groups, including the notorious Abu Sayyaf, which turned to terrorism and banditry after losing its commanders early in battle. The Abu Sayyaf has been blacklisted by the United States as a terrorist organization and has been suspected of staging a suspected January 27 suicide bombing that killed 23 mostly churchgoers in a Roman Catholic cathedral on southern Jolo island.

“We have already seen the pitfalls,” Al Haq said, acknowledging that the violence would not stop overnight because of the presence of the Abu Sayyaf and other armed groups, some linked to the Islamic State group. “It’s a very difficult and challenging process.”

Sidney Jones, a Jakarta-based analyst for the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, said three of the biggest challenges will be finding a meaningful role for ex-combatants, avoiding a sense of entitlement that leads to corruption, and “staying united in a way that can finally break the power clan politics in Muslim Mindanao,” referring to the southern region that is the homeland of minority Muslims in the largely Roman Catholic nation.

Under the peace deal brokered by Malaysia, the rebels gave up their goal of a separate state in exchange for broader autonomy. The 40,000 fighters and at least 7,000 firearms that Murad’s group has declared would be demobilized in three phases depending on progress in the agreement’s enforcement.

Bangsamoro replaces an existing poverty-wracked autonomous region with a larger, better-funded, and more powerful entity. An annual grant, which could reach more than $1 billion, is to be set aside to bolster development in a region deeply scarred by decades of fighting.

Centuries of conquest — first by Spanish and American colonial forces that had ruled the Philippine archipelago followed by Filipino Christian settlers — have gradually turned Muslims into a minority group in Mindanao region, triggering conflict over land, resources, and sharing of political power.

Uprisings seeking self-rule have been brutally suppressed by government forces, feeding more resentment. Security has been a major issue due to the proliferation of firearms and armed groups that have resorted to ransom kidnappings and extortion such as the Abu Sayyaf.

By Jim Gomez for The Associated Press.