On February 14, a 20-year-old Kashmiri militant, Adil Ahmad Dar, rammed an SUV full of explosives into an Indian paramilitary convoy truck in Pulwama, Kashmir, killing himself and more than 40 Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) personnel. The attack in Pulwama was the deadliest against Indian forces in the three decades of armed conflict in Kashmir. In an immediate response to the suicide attack, the Indian government accused Pakistan of supporting Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), the group that had taken responsibility for the attack. Soon thereafter, India carried out aerial strikes across the international border inside Pakistani territory, the details of which are still unclear and contested.

After Pakistan took retaliatory action, the international community focused its attention on the danger of any escalation between the two nuclear powers. The threat still looms large, even as Pakistan has safely returned Indian Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman, who was captured alive by the Pakistani military after his aircraft was shot down inside Pakistani territory. Cross-border shelling continues from both sides, killing military personnel and civilians on daily basis. Various countries, including the United States, spoke up to counter the escalation of hostilities.

The Pulwama attack was the result of a signal being sent to militants that spectacular, high-casualty attacks are the only way for armed groups in Kashmir to draw attention to their cause of self-determination. This assumption was proven correct by the immediate uptick in diplomatic activity and international attention on the otherwise-ignored Kashmir after the attack in Pulwama caused India and Pakistan to come to the brink of an all-out war. However, the increase in diplomatic activity and the attention of world community should not be directly linked to the danger of war between the two countries. Rather, it should be drawn to the cause that makes such a war possible: the conflict over Kashmir. As long as it remains unresolved, the conflict will continue to trigger such confrontations, with the scare of a nuclear war looming.

Is Kashmir Really a Low-Intensity Conflict?

Before the Pulwama attack, Kashmir was becoming a footnote in the long list of ongoing international conflicts. India’s counterinsurgency regime has been “flushing out” militants, often poorly trained and scarcely armed, in higher numbers than the decade prior. Recruitment by militant organizations continues to be more local and militants no longer receive the degree of training and arms they did in the 1990s from across the border in Pakistan. Militant commanders have expressed their dissatisfaction against Pakistan publicly for not strongly pushing for the cause of Kashmiris diplomatically. Besides Pulwama, militants had not been able to sufficiently increase the costs of counterinsurgency in the last decade to gain the attention of the Indian government or the international community.

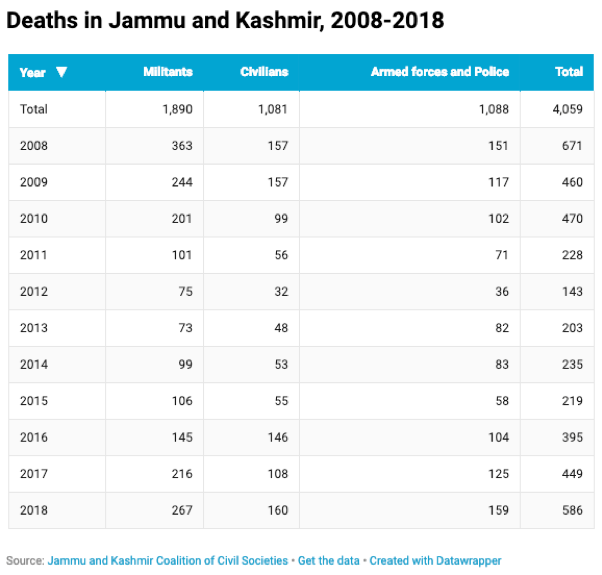

Some analysts refer to Kashmir as a “low intensity” conflict because the violence is localized. However, this characterization hides the human costs of this conflict, which has been going on for the last 70 years. The following table shows the loss of life in the last decade.

In the last decade, 405 persons (civilians, militants, and security forces) have been killed on average each year. The average number of combatants killed each year in the same decade is 297. These killings are all battle-related so, as per the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, the conflict in Kashmir is “active” and given the average number of killings each year, the conflict tilts closer to being an active war (at least 1,000 battle related deaths). However, it continues to be referred to as a “low intensity” conflict because these deaths are scattered throughout the calendar year.

Kashmir as a Nuclear Flashpoint

Though these killings in Kashmir have persisted – and been disregarded – over the last decade, it was the deaths of 40 paramilitary forces in a single day that caused Pakistan and India to come to the brink of war. The post-Pulwama confrontation between the two neighbors is said to be the worst conflict between the two nations since India invaded Pakistani airspace for the first time since 1971. Mainstream media in India, including a large number of Bollywood celebrities, demanded that Pakistan be taught a lesson. Sections of the media in Pakistan ran provocative headlines while a number of the public figures in the country said no to war. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said the forces of his country have a free hand; his counterpart in Pakistan said “This issue should be solved through dialogue.” The airspace was suspended for civilian flights for hours in India and for almost a week in Pakistan, hospitals in Srinagar painted their rooftops with the Red Cross symbol, and villages were even evacuated near the Line of Control (LoC). Heightened preparations suggested that a full-blown war could break out at any moment.

The conflict over Kashmir, therefore, continues to have the potential to spark a nuclear war in South Asia; any such attack against the Indian forces in the future may incite a similar blame game and military confrontation. The tragedy, however, is this: only higher numbers of casualties of security forces draw the attention of the government, while the killings of Kashmiris in “ones and twos” pass as normalcy.

The Pulwama attack was therefore the result of a tacit message being sent to militants that organized, high-casualty attacks are the only way for groups to attract attention, achieve legitimacy, and bring international actors to the negotiating table. The evidence from Afghanistan seems to suggest this may be a strategy that works: the Taliban have repeatedly carried out gruesome attacks, killing hundreds of civilians and security forces across Afghanistan to push the United States to negotiate with them. In the last 17 years, since the beginning of the “war on terrorism,” close to 147,000 people have lost their lives in Afghanistan alone.

Kashmir, in comparison, has not witnessed killings on such a scale, although the numbers are high if we take stock of the total deaths in the last three decades. For years now, the violent counterinsurgency strategies applied by the Indian state appeared to have incapacitated militant organizations, whose members barge into residential apartments and steal guns from local policemen. The Indian security apparatus was more than confident that continuing “operation all-out” into 2019 would have eliminated Kashmiri militancy completely. The attack in Pulwama, however, has forced the Indian state to recalibrate its strategy. In the immediate response to these attacks, the Indian government initiated a crackdown against the Jamaat-e-Islami in Kashmir, a national Islamist party, arrested its leadership, and later banned the organization. Jamaat, the order said, is in “close touch with militant outfits” and is likely to “escalate its subversive activities including attempt to carve out an Islamic State out of the territory of Union of India.”

While the Indian crackdown on pro-freedom groups in Kashmir continues, international diplomatic efforts are focused on mending the relationship between the two neighboring countries. The United Nations Security Council issued a statement condemning the Pulwama attack. Amid tensions, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) invited the Indian foreign minister for the first time, which led Pakistan to boycott the summit. Following the summit, the OIC passed a resolution criticizing “Indian brutalities” in Kashmir and also praised Imran Khan for his efforts to deescalate tensions. Overall, activity on the international stage has sent mixed signals on the possibility of ending the lasting dispute. More needs to be done specifically about the conflict over Kashmir.

A Crucial Role for the International Community

Preparations for an all-out war, an increase in diplomatic activity on the Kashmir issue, a renewed international focus on Kashmir as a nuclear flashpoint, and the repression of pro-self-determination groups in Kashmir happened only because the attack in Pulwama resulted in an unprecedented number of casualties to armed forces. With such a large number of casualties and Indian elections looming, warmongers were able to clamor for retribution against Pakistan and create a hostile atmosphere that led to attacks against Kashmiri people across India. This, in turn, brought greater international attention and diplomatic efforts to the Kashmiri cause of self-determination.

If there was doubt before, the message that is now being delivered to militants is that a higher number of casualties keeps the Kashmir issue in focus, and will perhaps draw the attention of great powers and international fora. To avoid more bloodshed in Kashmir and all-out war between the two nuclear-armed adversaries in South Asia, the international community should make a concerted effort to address the root cause of the conflict by pushing India and Pakistan to the negotiating table with the people of Kashmir.

Basharat Ali is a Ph.D. student at the Jamia Millia Islamia University’s Academy of International Studies in New Delhi, India. A version of this piece originally appeared at South Asian Voices, an online platform for strategic analysis and debate hosted by the Stimson Center.