Chinese President Xi Jinping and senior military leaders met with Myanmar’s commander-in-chief this week, as Senior General Min Aung Hlaing paid an official visit to Beijing. It was the fifth time Min Aung Hlaing has visited China since assuming his current post as the top leader of Myanmar’s military forces, the Tatmadaw. In Myanmar, where the military retains a constitutionally-mandated grip on political power despite holding elections in 2015, that makes Min Aung Hlaing a top political leader as well, and the topics of conversation during his China trip reflected that.

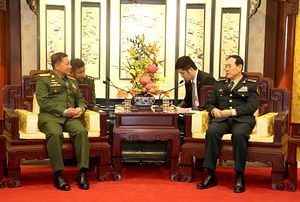

Min Aung Hlaing’s official host was Chief of the Joint Staff Department General Li Zuocheng, but he met with a variety of Chinese military officials, including Central Military Commission Vice Chair Xu Qiliang and Defense Minister Wei Fenghe, on Tuesday and Wednesday. Min Aung Hlaing also met with Xi on Wednesday. At each of these meetings, both sides took care to praise the longstanding – “eternal” even – friendship between their countries and expressed hope for deepening cooperation still further in the future. “Myanmar regards China as an eternal friend and a strategic partner country,” Min Aung Hlaing said, according to a press release from the Tatmadaw.

“China has always supported Myanmar and will continue to do so,” Xi said, for his part.

For decades, China was Myanmar’s lone major international partner — the Southeast Asian state faced pariah status abroad for its iron-fisted military rule and persecution of pro-democracy advocates like Aung San Suu Kyi. When the Tatmadaw began moving toward some political opening, resulting in Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) winning a landslide electoral victory in 2015, it opened up new options for Naypyidaw’s international engagement, sparking concerns in Beijing about the increased competition.

However, the military’s ruthless campaign against the Rohingya minority group in northern Rakhine state once again has more liberal-minded partners shying away. A United Nations fact-finding mission into the Rohingya crisis recommended that “senior generals of the Myanmar military should be investigated and prosecuted in an international criminal tribunal for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.” The same report names Min Aung Hlaing specifically as one of the “priority subjects for investigation and prosecution.”

But China has kept up its support for the Myanmar military in the name of its long-standing noninterference policy. CMC Vice Chair Xu told Min Aung Hlaing that China “support[s] Myanmar in following a development path in line with its own national conditions,” effectively Beijing’s way of saying that what happens in Myanmar stays in Myanmar, as far as Chinese leaders are concerned. Notably, Min Aung Hlaing made a special point of thanking China “for its correct stance and standing against the international community over the Rakhine state issue” in his meetings with military leaders.

While China might not care much about the Rohingyas, there are other problems in the relationship. For one thing, the influx of refugees across the Chinese border during ramped-up military operations in northern Myanmar remains a recurring problem. Meanwhile, Beijing has long been suspected of supporting certain armed ethnic groups in northern Myanmar, particularly the United Wa State Army. Seven of these armed groups have formed their own alternative to Myanmar’s state-based peace process, and there are suspicions that China is using the bloc to “gain leverage over the country’s peace process.” Beijing even provided funds – and a push – for all seven armed groups to attend the third Myanmar Union Peace Conference last summer, demonstrating its influence.

With that background, the question of conflict in Myanmar’s north is one of the main issues between the neighbors. Predictably, it featured prominently in the discussions this week. Min Aung Hlaing promised to ensure “stability in border areas” and China gave verbal support for Myanmar “achieving domestic peace and national reconciliation.” Xi himself offered China’s backing for the peace process, while also suggesting that the two sides should “further enhance joint border management.”

More interesting was the time spent discussing what should be primarily an economic issue: China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a massive investment project spanning the Eurasian continent as well as Africa, Latin America, and even the polar regions. In his meeting with Xi, Min Aung Hlaing pledged that “the Tatmadaw will cooperate” with China’s BRI, because “it includes several projects benefiting Myanmar.” He also noted that China is the largest investor in Myanmar. The senior general gave the BRI his vote of confidence, describing it as “a feature of showing goodwill towards world countries” and predicting success for Xi’s pet project.

The BRI has come in for criticism before, with some dismissing it as a “debt trap” for developing countries. Myanmar has joined up to the initiative, but individual projects continue to face controversy and pushback from local communities due to both a lack of transparency and concerns about environmental impacts.

The controversial Myitsone Dam project is the most famous example of a Chinese project gone awry in Myanmar. The dam has been in the works for nearly two decades – long before the BRI was rolled out in 2013. An agreement was signed for China to fund and build the dam in 2009, but the Myitsone Dam faced sweeping opposition among Myanmar’s people. In 2011, it was suspended and – despite continuous protests and pressure from Beijing – remains defunct today.

Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s civilian leader, is expected to attend the upcoming Belt and Road Forum in Beijing at the end of the month, where she will likely face pressure from China to restart construction on Myitsone Dam. That makes Min Aung Hlaing’s ringing endorsement of Chinese investment and the BRI all the more interesting.

There continues to be a tug-of-war over state policy between the NLD and the Tatmadaw. In Beijing, Min Aung Hlaing made no pretense about who he thinks should be driving the bilateral relationship with China. “The friendship between the two countries will be cemented through cooperation between the two armed forces,” he told his military counterparts. China, however, will be happy to work with whoever will give it what it wants, whether that is Aung San Suu Kyi or Myanmar’s commander-in-chief.