New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern arrived in Beijing on April 1 for a state visit. Ardern’s first visit to China, nearly 18 months after she took office, came on the tails of a tragic terrorist attack on two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand and amid signals of possible cracks in the bilateral relationship. The original plan for the trip included stops for Ardern and a business delegation to three Chinese cities over the course of a week, but the visit was first postponed and then cut down to just a one-day turnaround.

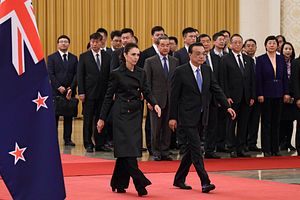

Ardern kicked off her visit by opening New Zealand’s brand new embassy in Beijing, proclaiming that, as one of the country’s “most significant diplomatic spaces in the world,” it was demonstrative of the importance of the China-New Zealand relationship now and moving forward. She later met with Premier Li Keqiang and President Xi Jinping, where the counterparts discussed the overall trajectory of bilateral ties, including trade and investment, and an expressed interest to further cooperation on climate change. Li called on New Zealand to provide a “fair investment environment,” a line no doubt designed to convey Beijing’s frustration over the Huawei debacle.

Both parties sought to reorient ties that had grown tense. Recent hiccups are not merely a product of leadership change in Wellington. Research revealing Chinese influence efforts in New Zealand’s politics and society has chilled ties, as have reports from New Zealand’s defense community framing China’s activities as a challenge to the existing international order and explicitly criticizing Beijing’s moves in the South China Sea. The latest dustup came as the New Zealand government blocked a bid from China’s Huawei to supply equipment to its national telecommunications company Spark’s 5G network in late 2018, after its intelligence agency cited security risks. (New Zealand is not alone in expressing concerns about Huawei; Australia, Canada, the Czech Republic, Poland, the United Kingdom, and the United States have all raised national security concerns and the telecoms giant’s network.)

The view from Beijing is that these moves are part of a calculated, U.S.-led effort to stymie China’s rise and destabilize the Asia Pacific region. In the lead up to Ardern’s state visit, the Global Times, a Chinese state mouthpiece, condemned “containment” but indicated that there was another way forward for Wellington. “In contrast to the strong-arm coercion by the US, there is in fact no pressure from the Chinese side at all to make Wellington choose between Beijing and Washington,” it said. Xi seemed to strike a more conciliatory tone on Ardern’s trip by saying that “China has always regarded New Zealand as a sincere friend and partner.”

Still, it’s important to note that the China-New Zealand rough patch is not emblematic of their history. Official relations were forged in the early 1970s. New Zealand’s ties with China over the past 20-plus years have long set a model for the type of relationship China would like to have with others in the developed world. In 1997, the island nation was the first Western country to back China’s accession to the World Trade Organization, and seven years later, it was the first to designate China as a market economy. New Zealand deepened the partnership in 2008 by signing China’s first free trade agreement with a Western partner, an FTA that the two committed to expand and renegotiate in 2016.

These moves have paid dividends for both Wellington and Beijing. Two-way trade peaked at more than NZ$27 billion (US$18.5 billion) in 2018, with New Zealand exporting dairy, wood products, and meat to China while importing machinery and clothing and apparel. Tourism and educational exchanges also factor significantly into the relationship: China is New Zealand’s fastest growing and second largest tourism market after Australia, with more than 80 flights between the two countries each week, as well as the largest source of international student enrollments in New Zealand.

But not all facets of the relationship are as rosy. China’s human rights record vis-a-vis Xinjiang was another dark cloud over the state visit, especially in light of Ardern’s response to and solidarity with the Muslim community in the aftermath of the deadly Christchurch attack. Ahead of Ardern’s trip, members of New Zealand’s Muslim community and rights groups urged the prime minister to take the lead on raising the issue of China’s so-called “re-education centers,” which have detained an estimated 1 million Uyghurs, a Muslim, Turkic minority. But Wellington knows that too bold or public of a statement may prompt retaliation from Beijing. New Zealand was noticeably absent from a November 2018 letter signed by envoys from 15 countries condemning China’s treatment of the Uyghurs.

Ardern faces a daunting challenge to balance her country’s extensive economic links to China with its security alliances and shared values with Western, democratic countries, particularly Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States — together, the so-called “Five Eyes” intelligence partners. New Zealand has taken pride in setting an example of how Western, developed countries can maintain strong, positive ties with China. And while periodic friction is inevitable between two countries of such different sizes and regime types, how Wellington navigates its ties with a more assertive and ambitious China may yet challenge the relationship’s resilience.