Rarely has a singular image become so powerfully potent that it is associated with the downfall of an entire regime. Throughout history, political and protest art has always accompanied any sort of popular struggle; yet surprisingly, even with the advent of social media, through which we often see a multitude of memes and GIFs, seldom are there single images that completely encapsulate public sentiment.

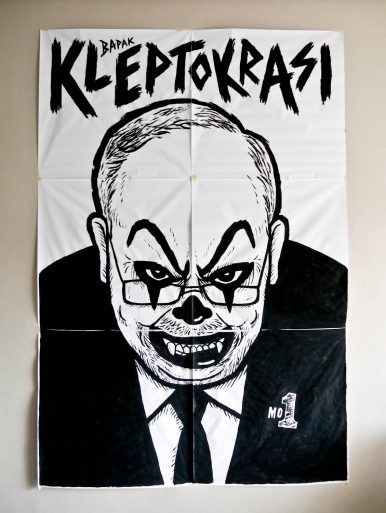

Fahmi Reza’s depiction of former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak as a clown is one such image. The artwork reverberated strongly with the discontent simmering among the Malaysian populace. The painted big red lips, coupled with that ghastly, almost zombie-like grin, evoked a deep-seated sense of betrayal and a breech of trust.

Fahmi’s “Bapak Kleptokrasi” (Father of Kleptocracy). Published with the artist’s permission.

Najib was deposed last year in May after the opposition Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition scored a surprising victory in the general election. His unpopularity had reached a fever pitch after almost 10 years in power due to a series of multibillion dollar corruption scandals in which he’d been implicated. The former leader and his close allies were allegedly involved in the laundering of at least $4.5 billion from the state’s 1MDB fund. Najib is now on trial.

For his work, Fahmi was arrested and charged in court for violating the Communications and Multimedia Act of 1998, which censors any offensive content posted online (the charges were later dropped). But the imagery he created had already taken on a life of its own.

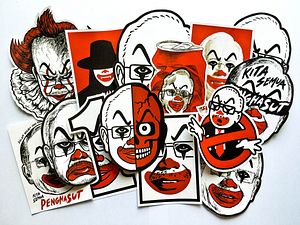

Blown-up, hand-held versions of his work were seen at demonstrations, or on walls as posters — some of which were put up by the artist himself. Similar works by other artists also contributed to the building storm of protest imagery. Fahmi saw this proliferation positively, not wanting to claim exclusivity over the indignation his works tapped into and incited.

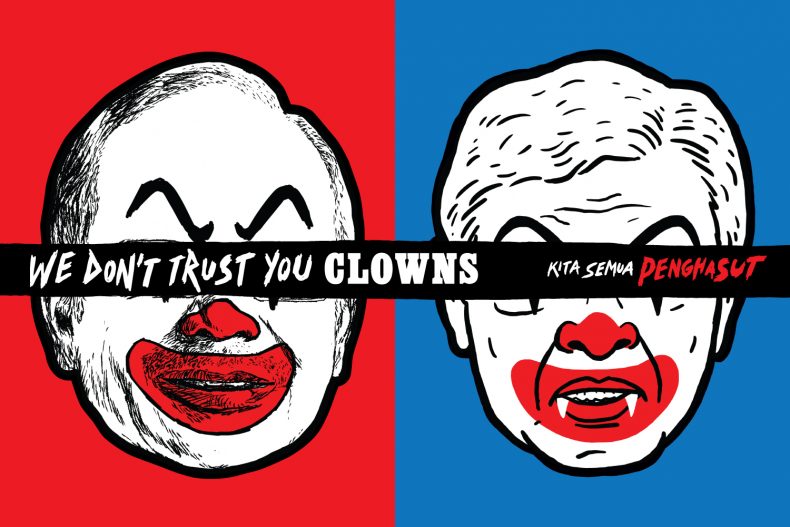

For proof of the effectiveness of his work, Fahmi points to groups allied with the previous administration that have copied his style for their own agenda — portraying current PH ministers as clowns, too.

“I guess the fact that the clown caricature is currently inspiring copycats, by groups led by individuals tied to the previous regime, it shows how impactful the original design was. First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win. And then they copy you,” he tells The Diplomat.

It has already been a year and Najib has only just sat down in court to face his crimes. The country, on the other hand, is infused with enthusiasm for the dawn of a more transparent age. But on the ground and in concrete terms, has a year really made a difference? And do the current signs point to comprehensive change?

What’s a radical street artist to do these days in Malaysia?

One of Fahmi’s pre-election artworks. Published with the artist’s permission.

Old regime, smoke of history

Liberty still wafting in the breeze

The new aristocracy just smells like the old regime (whoa)— From Bad Religion’s 2019 song, “Old Regime”

An admirer of punk music and its general disdain for the power held by the establishment, Fahmi invokes a spirit of skepticism toward purported democratic reform. He mentions that while the current situation is a drastic improvement on the kleptocracy of the Najib administration, it would be foolish to think that the country had rid itself of pernicious problems of repression over the course of a single year.

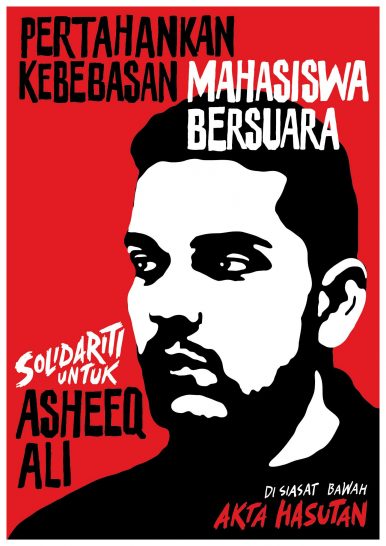

Poster in solidarity with a student activist (Asheeq Ali) who was investigated by police under the controversial Sedition Act over his speech during a protest. Published with the artist’s permission.

“The democratic reforms that were promised are progressing at a snail’s pace. Most of the election promises have not been fulfilled. Almost all of the draconian laws that they pledged to abolish are still in place. For example, the controversial colonial era Sedition Act that has been misused and abused by the previous regime is still being used to investigate activists until today,” Fahmi says.

In March, seven activists who had organized a march on on International Women’s Day were told by the authorities that they could face charges of sedition.

Fahmi has known many people who have been victimized by the Sedition Act, a type of law on the books in most authoritarian countries to quell critical speech or activity.

A report by Human Rights Watch on Malaysia covering the entirety of 2018 notes that certain laws that have become the bane of free speech and justice are still widely utilized by the authorities in Malaysia. Before he left power, Najib passed the Anti-Fake News law, which, like the Sedition Act, vaguely defines what can be considered “fake” or malicious information. The law has since been used to target state critics.

The state also continues to employ the Prevention of Crime Act and Prevention of Terrorism Act, both of which have received widespread criticism for being draconian. The laws permit arrests and detention without a trial. The new administration has pledged to abolish such laws, but has yet to do so.

Peaceful assemblies by various groups continue to be hounded by the police. Around 50 members of the Parti Sosialis Malaysia, for example, held a demonstration to submit an appeal to the new government last June. Police subsequently lodged complaints against them under the Peaceful Assembly Act, which requires strict permission and guidance from the authorities to hold public gatherings.

“We’re still struggling to see real social and political change in this country,” Fahmi says.

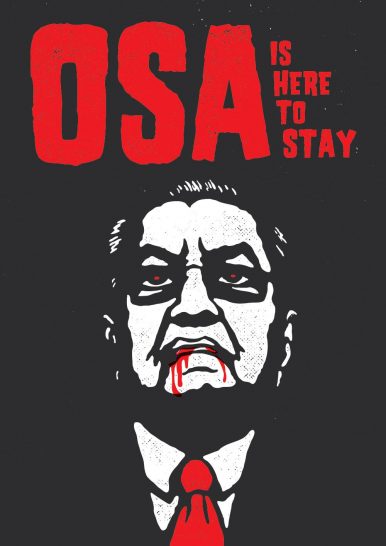

Poster criticizing Mahathir’s decision to renege on his ruling coalition’s election pledge to abolish the Official Secrets Act (OSA). Published with the artist’s permission.

Design of Dissent

Among Fahmi’s new artworks are pieces criticizing current Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad for backtracking on a campaign promise to do away with the Official Secrets Act (OSA). The much maligned OSA has been often cited as the reason behind the lack of transparency among public officials and as such creates a greater propensity toward corruption.

“Part of my work is still focused on challenging and dismantling the myths that keep the system alive. And my protest art is still focused on highlighting any forms of corruption or wrongdoing by the people in power,” Fahmi says.

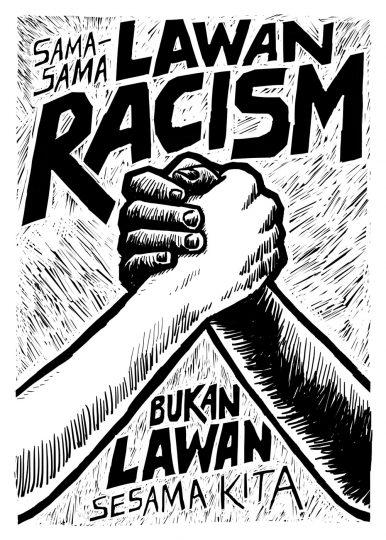

Ranging from corruption, racial inequalities, and oppression to crackdowns on progressive movements, Fahmi maintains his charge toward helping a nation visualize its own crisis of democracy. After all, how can we envisage any notion of political problems without having an imprint of it in our heads?

“The old regime was overthrown, but the pillars that supported the previous regime are still standing,” he affirms.

For Fahmi, the art didn’t stop with the downfall of Najib, nor his current criminal trial. The space has actually opened up for greater struggles and in his case, a larger audience of those who have just awakened to political life.

“Protest art can inspire and motivate, and can be used as a tool to raise awareness and to wake people up,” Fahmi says. “It can move people to take action, to bring down their government. And as a medium of protest, it can also be a tool to push for social change.”

A post-election poster against racism and racial sentiments still being used by politicians, “fight racism not each other.” Published with the artist’s permission.

In spite of the enormous pressure placed on Mahathir to steer the country away from the bleak times it has been through recently, he has failed to impress the likes of Fahmi in his first year in office. Perhaps that’s not surprising, as Mahathir himself spent the bulk of his political career as a key part of the establishment, serving as prime minister from 1981 to 2003 If anything, Mahathir has epitomized stagnation — and a persistent climate of crackdowns and harsh human rights violations.

As long as those remain, artists like Fahmi will exist. He has certainly garnered international appeal for his work, and the world is watching for what happens next in Malaysia.

“In countries where government critics are persecuted, dissidents are silenced, and political opponents are jailed, we need more artists and more designers to rise up and have the courage to stand up against injustice, using their art as a weapon of protest and resistance,” Fahmi says.

Michael Beltran is a freelance journalist from the Philippines.