At the third Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Summit held in Bangkok on November 4, leaders announced that participating countries had concluded “text-based negotiations” for “a modern, comprehensive, high-quality, and mutually beneficial” RCEP agreement. Lawyers and linguists will now step in to “scrub” the text before it can be put up for formal signature, possibly in February 2020, and ratification will follow.

RCEP negotiations got underway in May 2013, originally involving 16 East Asian countries: the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) plus China, Japan, Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and India (the six countries with which ASEAN had existing free trade deals). India pulled out in the last minute largely due to domestic political pressure and organized rallies against the deal, which critics claim will open India to the flood of Chinese consumer products and agricultural goods from Australia and New Zealand. Nevertheless, there are signs that India may reunite with RCEP partners should they accommodate India’s “core interests” in relation to market access, rules of origin, and automatic safeguard mechanisms among others. India should be welcomed to rejoin if and when it is ready.

Despite India’s withdrawal, the 15-nation RCEP (RCEP15) is still poised to be the world’s largest mega-free trade agreement (mega-FTA). The fast-growing RCEP15 participants collectively encompass around 30 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) and population.

At the same time, RCEP is a high-quality, forward-looking trade deal designed for 21st century international commerce. In comparison with the World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, RCEP incorporates a balanced mix of WTO-plus commitments to further lower at-the-border trade barriers and WTO-extra provisions aimed at addressing behind-the-border regulatory issues. It has dedicated chapters on Small and Medium Enterprises, Electronic Commerce, and Dispute Settlement while setting out broad procedures for inter-state Economic and Technical Cooperation for common prosperity.

Going forward more significantly, RCEP has the potential to serve as regional trade standard setter as the rules it settles on will probably become benchmarks and legal precedents for future trade deals in Asia and beyond. This is especially the case when RCEP opens up for new member applications from across the globe.

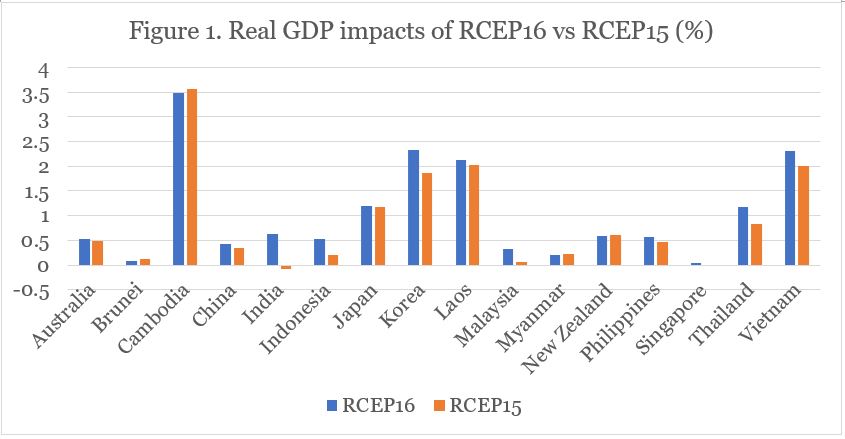

Will India’s absence reduce the economic benefits of RCEP? The answer obviously is yes because India is the fifth largest economy in the world, the third largest member of RCEP16, and a growing country of over 1.3 billion people. But our empirical economic analysis using an advanced GTAP model and assuming complete tariff removal suggests that the adverse impacts of India withdrawal are not too high and are manageable — except for India (see Figure 1). All 15 countries would see real GDP gains and RCEP15 would generate a real GDP increase of approximately $137 billion in the longer run. This is about 80 percent of what would have occurred under RCEP16 ($171 billion).

Data from author’s GTAP simulation.

As India in RCEP represented both a lucrative market and a formidable competitor for other participants, India’s exit necessarily means a simultaneous loss of preferential market access to and export competition with India from the perspective of remaining countries. As such, RCEP countries that have an export profile similar to India’s — like Cambodia, Brunei, New Zealand, and Myanmar — would be better off in the absence of India. But for those that primarily value India as an important export destination rather than an export rival, including foremost South Korea, Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam, India’s pull-out is projected to cut into their respective economic gains. That said, it is in fact India that would have to forego the largest amount of economic benefits by staying outside the trade bloc.

RCEP countries taken together account for 21 percent and 34 percent of India’s exports and imports, respectively. India projected gain of 0.62 percent of real GDP, or $12.6 billion, therefore would turn into a 0.08 percent ($1.6 billion) loss given trade diverting dynamics. In terms of sectoral impact, rejecting RCEP protects India’s processed food industry at the expense of the production and exports of all the other key economic and employment sectors including textiles, extraction, agriculture, forestry, fishery, and manufacturing. These quantifiable economic losses risk becoming worse should India be perpetually isolated from the sprawling East Asian regional value chains that will be facilitated, consolidated, and upgraded by RCEP15.

Beyond the numbers, the conclusion of RCEP talks took place during a crucial time for global economic governance. RCEP will give a timely boost to multilateralism, which is in retreat in other parts of the world where governments revert to nationalist and occasionally unilateralist policies. Just when the United States erects tariff walls and undercuts the functioning of the global trading system in the name of “America First,” Asian countries, by forming a massive and high-standard RCEP, signal their collective resolve to upholding multilateralism in keeping with a rules-based, liberal, and cooperative international economic order.

With RCEP conclusion and the implementation of the 11-nation Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) in ratified countries, Asia now can harness two mega-FTAs to drive forward deep integration in the region. The relationship between the China and ASEAN-led RCEP and U.S.-led TPP, the predecessor of CPTPP, had been characterized by acrimonious Sino-U.S. geopolitical competition. But since President Donald Trump terminated America’s TPP membership in 2017, Asian countries have come to view the two mega-FTAs as complementary in nature.

Considering that seven countries (Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam) are party to both CPTPP and RCEP, there is strong basis for an orderly convergence between CPTPP and RCEP insofar as political will is present. A merger of RCEP and CPTPP will strengthen “ASEAN Centrality” while also laying the groundwork for the establishment of a truly inclusive Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific, a long-held and aspirational goal of Asian economic regionalism.