In 2019, India has the highest number of internet shutdowns in the world – 102 and counting. These are just the documented incidents. Some estimate that the actual number could be even greater.

Access Now, a global nonprofit advocating for a free and open internet, states that “an internet shutdown happens when someone – usually government – intentionally disrupts the Internet or mobile apps to control what people say or do.” Critics have argued that internet shutdowns in India are in direct violation to the right to freedom of speech and expression granted under Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution.

The United Nations has condemned internet shutdowns as a human rights violation, stating that it violates article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which guarantees everyone a right to freedom of expression. A 2016 resolution by the UNHRC clearly states that “the same human rights that people have offline must be protected online.”

Initially localized to certain states like Jammu and Kashmir, the practice of internet blackouts by the Indian government has become increasingly common across the nation. On December 19, 2019, as the student movement against the new Citizenship Amendment Act grew, the government shut down the internet in parts of New Delhi, India’s national capital.

The deputy commissioner of the Delhi Police signed a notice stating that the “prevailing law and order situation” was the reason to shut off voice, SMS, and internet services in the area.

The student-led protests across the country are in opposition to the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). The CAA, passed by the Indian government on December 12, 2019, allows non-Muslim persecuted minorities from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan to obtain Indian citizenship. Critics, like the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, have called it “fundamentally discriminatory” as it excludes Muslims.

Muslims are India’s largest religious minority, making up 14 percent of its population. Some fear that the CAA could possibly marginalize India’s 1.9 million Muslims in Assam and more around the country if combined with the controversial National Register for Citizens (NRC) proposed in August 2019. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party has denied discrimination based on religion.

Nevertheless, when questioned in the Lok Sabha, Amit Shah, India’s home minister and one of the chief architects of the bill, replied that “there is a fundamental difference between a refugee and an infiltrator. This Bill is for refugees.” Shah was othering the Muslim immigrants as “infiltrators.”

Moreover, the police’s brutal clampdown on student protesters of Jamia Millia Islamia and Aligarh Muslim University last Sunday pushed students across the country and globally to speak up against the current regime.

As of now internet remains off for many parts of the Kashmir Valley since India abrogated Article 370 of the Indian Constitution on August 4, 2019. More recently, just in the last week, the internet was shut off for the northeastern states of Assam, Meghalaya, and Tripura (affecting some 36 million people), amid their protests against the CAA. Some other areas where internet has been shut off in response to the CAA protests include large swaths of West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh (which holds 200 million people), Mangaluru, Lucknow, Bareilly, Ghaziabad, and Dakshina Kannada.

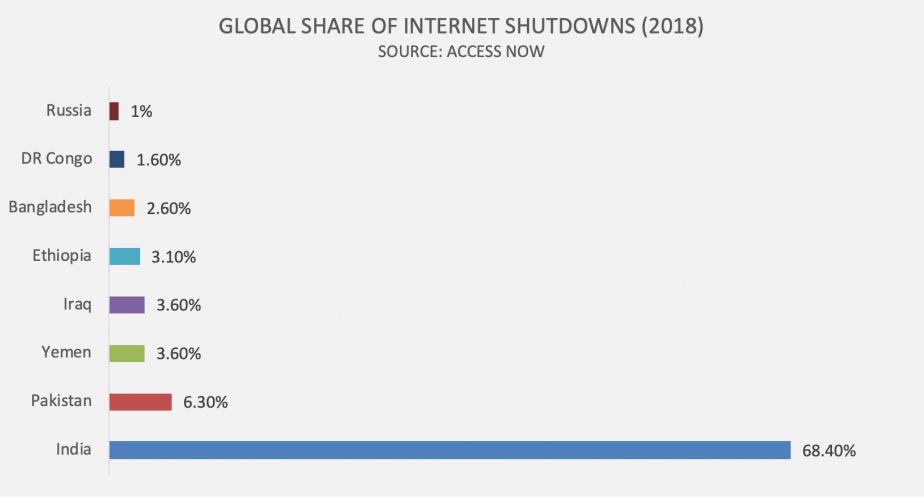

In the last year, 68 percent of the world’s total internet shutdowns were reported in India. Some other countries that have utilized this tactic include Pakistan (12), Yemen (7), and Iraq (7). In comparison, India had a staggering number of 134 internet shutdowns in 2018.

Shutdowns are legitimized through the provision of two colonial-era laws – Section 144 of India’s Code of Criminal Procedure and the Indian Telegraph Act of 1885. Section 144, presently imposed in many parts of the country, allows state governments to issue orders for immediate remedy in urgent cases of nuisance or apprehended danger. It also disallows the assembly of more than four people in an area.

The Cost of Shutdowns

Most of the recent shutdowns have been categorized under “preventative actions” according to an internet shutdown policy tracker by Software Freedom Law Centre (SFLC.in), an Indian internet watchdog that has been tracking internet shutdowns since 2012.

However, it may have the opposite effect. Research by Jan Rydzak, the associate director of Stanford University’s Global Digital Policy Incubator, shows that the abrupt shutdown of social media and digital platforms in India can change “a predictable situation into one that is highly volatile, violent, and chaotic.”

As news becomes increasingly digital, an internet blockade makes it impossible for reporters and newspapers to spread information and report on events of national consequence. Internet shutdowns can often act as a “cover” for state violence, like in the case of Sudan, as reported by Access Now. Globally, it finds there were at least 33 incidents of state violence in 2018 during internet shutdowns.

Almost half a billion people are online in India and around 97 percent of India’s internet users use their mobile phones to access the internet. Many of the internet shutdowns are mobile internet shutdowns. These not just worsen the situation on the ground but also impact various areas of life from business to access to healthcare and education.

From 2012-2017, the Indian economy lost $3.04 billion due to internet shutdowns, according to a report by the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations. Shutdowns have only increased rapidly since 2017, doubling in 2018 and nearing 100 in 2019. The Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KCCI) estimates that the lockdown has cost $2.4 billion since the revocation of Article 370 and imposition of an internet shutdown in the valley, reports Reuters.

Prolonged lack of internet access also makes it difficult for hospitals and pharmacies to order and restock life-saving medicines and surgical equipment, leading to avoidable health casualties, according to reports by the New York Times and the internet watchdog SFLC.in. Furthermore, students could lose access to educational opportunities as many college and fellowship admissions are online.

There is an increasing overuse of internet shutdowns by states in India. While largely used during elections and protests, some parts of India have also used internet shutdowns as a tactic during examinations to prevent cheating. A recent ruling by the Jodhpur High Court regarding the suspension of mobile services for the police constable recruitment examination barred Rajasthan from imposing mobile internet shutdowns during any examinations in the future.

The Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi initially came into power with “Digital India” as one of his flagship programs. It aimed to transform India into a “digitally empowered society and knowledge economy.” However, as internet shutdowns spread across the country, millions of Indian citizens languish in government imposed digital darkness.