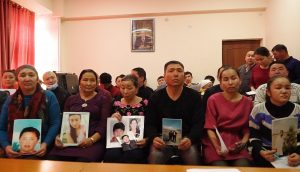

It was a cold February day in Kazakhstan. Outside a small village house in Qarabulaq, a village near Taldykorgan in Almaty province, as many as a hundred people gathered, waiting since the early morning to enter. Inside the house, volunteers with Atajurt — myself included — recorded close to 60 video testimonies from people whose loved ones had been detained in Chinese prisons, concentration camps, and forced labor factories. After personally conducting about 40 of the interviews (it was my personal record with Atajurt), translating from Kazakh into English and Turkish, I collapsed with exhaustion at the end of the day. There were still people waiting outside to tell their stories.

The day before we were in the town of Tekeli, where we worked from a relatively large and comfortable restaurant. We had three cameras purchased through donated funds raised by generous Kazakhs concerned for those in Xinjiang. Three of us from Atajurt, including Serikjan Bilash himself, translated video testimonies into English, Chinese, and Turkish while other Atajurt volunteers helped people prepare written petitions.

A month later, Serikjan was detained. His detention was widely covered by the international press. International human rights organizations campaigned for his release.

The Atajurt Kazakh Human Rights Organization has provided enormous amount of information about the Chinese concentration camps and the dystopian regime in Xinjiang. We have hosted journalists from all around the world including Hong Kong, Japan, Russia, the United States, Canada, Britain, France, and Germany, among others. Serikjan played such a crucial role in documenting the tragedy in Xinjiang that his arrest triggered a wave of international outpourings of support. Leading media outlets including CNN, the BBC and the New York Times had all visited Atajurt’s office in Almaty; journalists and human rights activists were aware of how valuable a source of information Atajurt was.

Nevertheless, Atajurt’s role, efforts, and scope of activities have rarely been truly acknowledged. So much so that, in a recent article by a Western journalist published under the title “How The World Learned Of China’s Mass Internment Camps,” Atajurt is not mentioned. In fact, credit is mostly given to Western journalists, academics, and human rights activists.

People are usually not aware of how much effort Atajurt volunteers are putting into this work. When foreign journalists visit our office, time and again they express their surprise to see so many people waiting for hours to talk to them; and only a small portion of them live in Almaty. It is easy to assume that Atajurt just makes an announcement and 50 people rush into our office. If only things were so easy. On an average day before Serikjan’s detention, we would organize interviews for foreign journalists, prepare written petitions for each and every victim, and record our own video interviews. On a busy day, like the day before Serikjan’s detention, more than a hundred people rushed into our office to ask for help from us and from foreign journalists. When we worked at full capacity from October 2018 to Serikjan’s detention on March 10, 2019, around two dozen volunteers dedicated their lives to the cause. As Gene Bunin, the curator of Xinjiang Victims Database, has said there would probably not be a Xinjiang victims database without Atajurt’s tireless work.

The majority of those who gave testimonies are uneducated or old; many hadn’t even known they could petition the authorities in the first place or ask for help from international human rights organizations. Atajurt volunteers have tirelessly and uncomplainingly taught these people how to write petitions, how to address authorities, and how to attract international attention. When I watch other Atajurt volunteers speaking to people, I am surprised to see how patient and humble they are. Serikjan knew each and every victim’s story; he had a talent for it. But other members too, including our current leader Bekzat, talk to each person who comes to us, one by one, and they never run out of patience. Guljan, one of our female volunteers who contacts people daily and is responsible for written petitions, told me that she has 67 WhatsApp groups related to Atajurt’s work. On 67 different groups, she responds to each and every message, keeps people informed about Atajurt’s activities, and encourages them to speak up.

Ignorance has not been the only challenge. It is now widely known that many people abroad have been afraid to speak up about their loved ones in Xinjiang. Many people also reported that at first they kept silent because they expected their relatives to be released soon. For these reasons, a majority of Uyghurs are still silent. Although the Kazakh population in Xinjiang is much smaller than the Uyghur population, I would estimate that almost 70-80 percent of the information about the concentration camps in Xinjiang came from Atajurt, especially in the early days of the struggle. Yet Kazakhs, too, were silent at the beginning due to both fear and ignorance. It took an enormous effort from Atajurt volunteers to encourage people to speak up.

Our trip to Taldykorgan and towns in the area last February was only one of Atajurt’s many trips to provinces and rural areas to collect testimonies. Taldykorgan (and Almaty province) has a large community of Kazakhs who immigrated from Xinjiang. Since 2017 Atajurt has also made two trips to Astana, three to Oskemen and Eastern Kazakhstan province, and one to Shymkent. In addition, individual Atajurt volunteers have traveled to rural areas to find people on many other occasions. It was largely thanks to these trips and Atajurt volunteers’ tireless efforts to encourage people to speak up that we have collected thousands of video testimonies and written petitions. Atajurt even covered the travel expenses of many testifiers since they did not have the means to come to Almaty. We now have written petitions and video testimonies for close to 3,000 individuals and around 5,000 testimonies in total. All the petitions we assist people in writing are sent to Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the United Nations. Following our petitions, thousands of people have been released and some have even made it back to Kazakhstan. More importantly, it was largely thanks to Atajurt that international media began to cover the Xinjiang tragedy more intensely in late 2018.

At first, Atajurt only collected written petitions. But Serikjan understood the power of media and in the summer of 2018 began collecting video testimonies. By September, he was translating testimonies into English and Chinese. Later a Turkish Kazakh started translating videos into Turkish and a Kazakhstani Uyghur into Arabic. Until Serikjan’s detention, we also regularly had testimonies in Russian and from time to time we had testimonies in German and French, too. In total, we have provided video testimonies in eight languages: Kazakh, Chinese, English, Russian, Turkish, Arabic, French, and German. Before his detention, Serikjan was planning to find people to translate testimonies into Korean and Japanese. We created a “wall of sorrow” in our office and provided an opportunity for journalists to visualize the tragedy. We organized numerous conferences dedicated to victims of particular counties in Xinjiang or to special topics such as detained imams. Thanks to these efforts, international media has been able to cover the stories of our desperate testifiers.

Atajurt now not only collects testimonies but has worked in other ways to help and support those whose relatives are detained in Xinjiang. We have financially supported families as well as Kazakh students from China who did not want to return to Xinjiang for fear of being detained. We have organized numerous charity events, especially to assist children. While the bulk of our work has been in collecting and disseminating testimonies, that does not encompass all that we do.

On November 18, we were again on our way to Taldykorgan. This was our first trip out of Almaty after Serikjan’s detention in March. While we, the volunteers of the main office in Almaty, were traveling to collect more testimonies, our office in the capital, established by our current leader Bekzat, organized a press conference at the National Press Club with the support of a few independent journalists. Fifteen of our long-time testifiers were there to talk to the authorities. Even though officials did not attend the conference as our testifiers expected, their stories were covered by mainstream Kazakh media in a rare instance; for the most part, Kazakh media have ignored our work. One week later, they organized an even larger press conference with the participation of more than 20 Atajurt testifiers. Related to these activities, Kapar Akhat, one of our volunteers in Nur-Sultan, was arrested on December 10 and imprisoned for 10 days. That same week, Sayragul Sauytbay, whose case was publicized and internationalized by Atajurt and who now lives in Sweden, went to the European Parliament together with an Atajurt supporter in Germany. Meanwhile, Bekzat and our volunteers continued to follow the cases of Kaster Musakhan and Murager Alimuly — two Chinese Kazakhs who escaped China and are now detained and applying for asylum in Kazakhstan.

Kazakh authorities declared at one point that they would return the two men to China. In addition, President Tokayev in December supported China’s policies in Xinjiang in an exceptionally pro-China statement. Atajurt continues its work, despite these monumental challenges. Serikjan Bilash’s charismatic leadership made Atajurt a significant organization; we have kept fighting for those detained and deprived of their rights in Xinjiang.

Serikjan was released in August, but he has been forbidden from engaging in any political or social activity for seven years. In addition, Atajurt experienced a split in September when two of our members did not recognize Bekzat’s leadership. After refusing for years to register Atajurt, the Kazakh authorities registered the splinter group under our name — the bulk of our volunteers kept working, unregistered, under Bekzat’s leadership. This was little more than an attempt by the Kazakh authorities to tame Atajurt.

The registered splinter group has done nothing but attack us and government pressure continues, too. We lost our former office in Almaty and some supplies and were subsequently expelled from two more locations. We have experienced serious financial difficulties.

But we continue in our important work under a new name: “Nagyz Atajurt Eriktileri” (Real Atajurt Volunteers).

What I like most about Atajurt is how open it is to all ethnic groups, even though it is run by Kazakhs. The majority of our testifiers are Kazakh, but we have had a few dozen Uyghur (and many more testimonies for Uyghurs by Kazakhs), a dozen Kyrgyz, and a few Tatar testifiers. We have also had testimonies for Dungans by Kazakhs. Our testifiers include citizens of Kazakhstan, China, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and from time to time even foreign academics. Recently, we had a Turkish testifier who could not get any response from the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and came to us for help. Atajurt provides hope for not only Kazakhs and this is all thanks to our volunteers’ tireless struggle. What makes Atajurt different from many other organizations is its volunteers’ enthusiasm and energy to fight against 21st century fascism while continuously facing challenges within Kazakhstan.

Mehmet Volkan Kaşıkçı is a Ph.D. candidate in Soviet history at Arizona State University. His research covers the social and cultural history of Kazakhstan in the 1930s and 1940s. He has been volunteering for Atajurt for a year now and he has personally done approximately 600 video interviews for Atajurt. He is the only foreign volunteer in the group.