In the wake of the novel coronavirus outbreak, much has been written about how China’s poor handling of the outbreak is directly connected to the regime’s lack of transparency and repressive instincts. The centralization of power under Xi Jinping leads local officials to enter a kind of paralysis, as discussed in the New Statesman and The Financial Times. Nervous about their actions being viewed as out of line with Xi, local officials opt to take no action.

During the five-day period between January 21 and 25, a vacuum of limited state rhetoric and even more limited government action emerged. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) slogan “有困难找政府” (if something is wrong, go to the government) seemed to be instinctively dismissed by those at the forefront of the Wuhan outbreak. Instead, netizens tried to fill that vacuum by asking each other for help. Rather than censors deleting these posts, state media such as People’s Daily encouraged help-seeking posts among civilians, re-posting them on Weibo.

Perhaps the public’s reaction to the virus on social media is proof that China’s civil society is alive and well. The five-day vacuum in both local and central government action and the coinciding explosion of a relatively uncensored civilian outcry demonstrates the impact that civil society can achieve when left to its own devices. But in China, public discourse and group organization are never left unchecked for too long. After the vacuum closed and the government’s voice stepped back into the forefront, those engaged in the online discourse soon faced retroactive repercussions justified by the charge of “spreading rumors.”

China banned spreading rumors in 2015, with a possible punishment of up to seven years in prison. This law effectively leaves it up to the authorities to determine what is real and what is rumor. Further complicated by the fact that “the authorities” are not one entity, but rather are comprised of many levels of police, party-state officials, and teams who serve as China’s censors, this law grants truth an ever-changing and hierarchically-determined definition.

Wang Xiaodong, the governor of Hubei province, claims that in Hubei, they have “more than enough materials and supplies” on January 23. This screenshot from CCTV was shared — and mocked — on Chinese social media.

Between January 21 and 25, netizens put out countless help-seeking posts that inevitably contained information pertaining to the spread of the virus: you can’t ask for help for your sick mother without acknowledging she’s sick; you can’t request more supplies for a hospital in your region without admitting it needs them.

In many cases, these posts were left uncensored during the vacuum period, but once the central government became actively involved — determining the appropriate level of worry and deciphering truth from rumor — the ability of regular people to post freely and without consequence came into question. In other cases, local officials used their legal rights to detain people for “spreading rumors” to prevent the truth from getting out, likely fearing how they might be punished for the spread of the virus to their own regions.

Control under the CCP functions in a constant cycle of push and pull. The five-day vacuum and its fallout is a clear example of how Beijing makes use of its centralized power to bide its time, with the knowledge and comfort that should anything go wrong, there are thousands of lower-ranking officials who could take the heat for it, not to mention troublesome or law-breaking citizens. Xi’s complete institutional and ideological control of the CCP, and the uncertainty and fallibility that control creates those below him, is a luxury he has no intention of squandering. We can see from the way it played out that the response to the Wuhan virus was no exception.

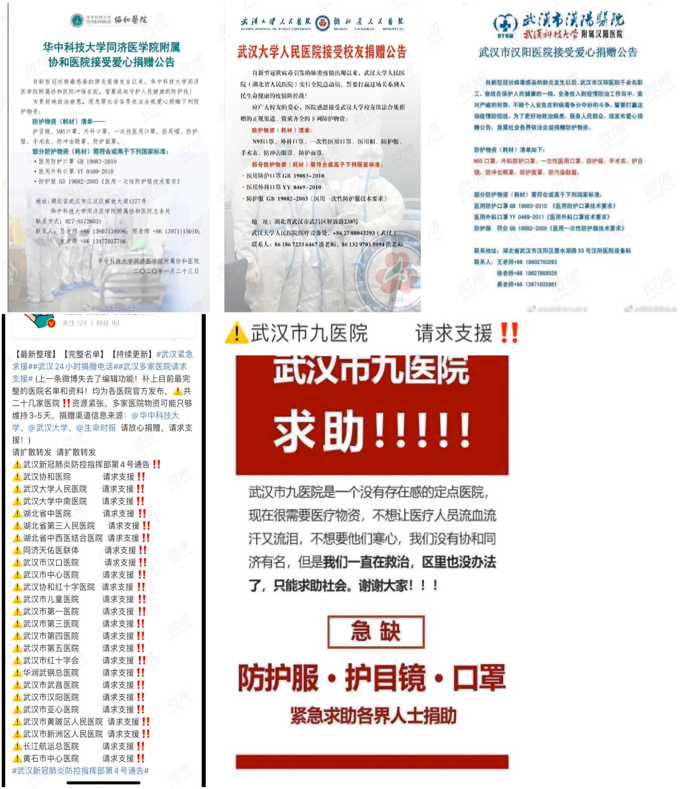

Social media postings from various hospitals inform netizens of urgently needed health equipment.

From Outcry to “Rumor”

According to a recently-deleted article in the Chinese-language mainstream media outlet Southern Weekly, (available here via a re-post), more than 160 hospitals were calling for help on social media up until January 28. The article explains that although hospitals are usually not allowed to seek help directly from the public, they did so during the Wuhan crisis out of desperation. Wuhan’s hospitals were the first to turn to the public, asking for direct donations from “society.” They posted the name of the hospital, what types of medical equipment and quantities they needed, and contact numbers.

In Wuhan, in late December, eight people who posted about the outbreak were detained and questioned on the grounds that they had “spread rumors.” Beijing Youth Daily interviewed one of them, a doctor, who remains anonymous in this article. The original article was published on WeChat and taken down the same day.

In the interview, the doctor recounted that he had posted about the emergence of seven confirmed cases of SARS at his hospital in Wuhan in a WeChat group with his university classmates.

The same evening, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission published a “red-headed document” (i.e. the most important No.1 document, usually for internal use), containing information regarding the emergence of an unknown pneumonia.

The doctor told Beijing Youth Daily he understood the severity of circulating information about a new virus. He wanted people to be cautious, but he could not control how they would react to the news. People in the group took screenshots and re-posted the information in other groups. “It circulated so fast, very soon people in other provinces knew of it,” he said.

He was summoned by his hospital directors to answer questions about his post. “They asked me repeatedly about the source of the information, and they asked if I realized that I had made a mistake by fabricating rumors. In the end, they asked me to write a self-criticism, admitting that the circulated information was not true.” On January 3, the police called him and asked him to sign a notice of admonishment (训诫书).

He and other healthcare professionals were told by the directors of their hospital not to post any relevant information online. He kept silent, but he knew the virus had spread when he started getting new patients with the novel coronavirus by January 7. The patients had matching symptoms, but doctors were not permitted to conduct a test to confirm.

The People’s Daily WeChat account on January 29 posted an update on the eight who were arrested, claiming that these people did circulate rumors because they originally said the virus was SARS (editor’s note: SARS was caused by a different coronavirus). The article then went on to list four kinds of rumors “we must strike hard on.” These include: rumors about the epidemic; rumors accusing the state of being incapable of controlling the epidemic, rumors about medical institutions that have failed to control the epidemic, or failed to cure the patients; and any other rumors that might lead to social disorder.

In Qingdao, Shandong province, four men were detained for posting that Shandong had its first case — again on the charge of spreading rumors — only to have the first official case acknowledged by authorities the next day.

The end of the government vacuum period was accompanied by a harder strike on “rumors,” wherein citizens have been encouraged to “avoid saying rumors, avoid spreading rumors” and even report any content others have posted that they believe to be “rumor.”

The end of the government vacuum period was accompanied by a harder strike on “rumors,” wherein citizens have been encouraged to “avoid saying rumors, avoid spreading rumors” and even report any content others have posted that they believe to be “rumor.”

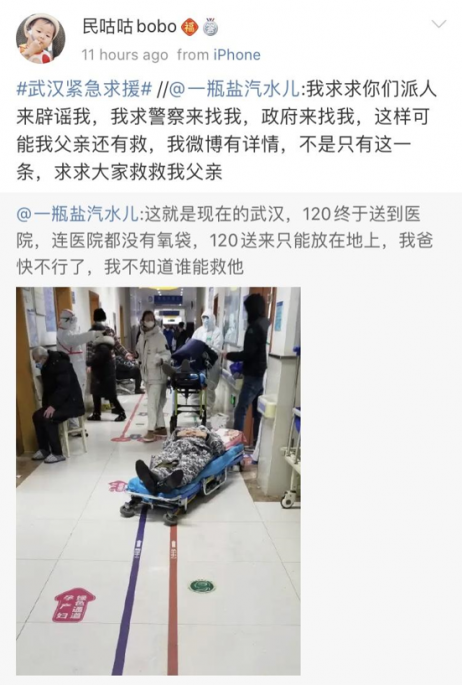

On January 27, a user going by Yu (@一瓶盐汽水儿) posted on Weibo that his father had been transported to the hospital but there was no oxygen available and his father was dying. The post was labeled a “rumor,” despite the picture he provided (see right). In the end, Yu had to go through a verification process with Sina Weibo just to avoid being labeled a “rumor producer.” In desperation, he posted, “Please, please, come and accuse me of being a rumor-maker, let the police come and catch me, let the government come after me, so my father might have a chance to live.”

Another netizen, @Greenfield, concluded that in order to seek help on Weibo, you have to meet a series of requirements: Any information you provide must be absolutely accurate (with “accurate” meaning your post has to match with the yet-to-come-out official statement); you must have abundant medical knowledge, as well as a great memory, even when your family is on the verge of dying; and you should avoid using a newly registered account, otherwise you might be a Taiwan spy who wants to bring chaos to the mainland. Even if you are finally able to verify your identity and people believe you are in real difficulty, the sardonic post continues, no one can do anything about it. But still, you can’t express any negative feelings — if you were to, say, complain about the bad situation in hospitals at the epicenter, then: “rumor alert!”

Confronted by an overwhelming amount of information coming from all directions during the vacuum period, plus the state’s hard attitude against “rumors” right afterward, the public has developed a paranoia about rumors. People who genuinely need help get nothing but ridicule, accusations, and abuse. The anti-rumor campaign is supposed to maintain stability and social order, but this is done to the detriment of the self-mobilizing civil society we witnessed during the five-day vacuum period. Those efforts abruptly collapsed before the powerful state machine, and people are again reduced to overwhelmed, isolated individuals with no other trustworthy source of information but the authorities.

Local Government as Scapegoat

On matters.news, a relatively liberal Chinese-language site that is banned within China, someone posed the question: Amid this crisis, why is everyone, from hospitals and doctors to regular people, seeking help from the whole of society rather than the government? Is it because they don’t trust the government, or is it because they’ve already tried to get help from the government and have found it useless?

“When it comes to the situation in Wuhan, the government is useless,” user @Ashtone wrote in reply on January 28. But the “uselessness” of the government seems to have been a conclusion many reached after trying to use government mechanisms and finding them ill-equipped.

The most common way people asked for government help was by calling the “mayor’s hotline.” On January 24, China Telecom posted on Weibo that on January 23 alone, the number of calls to the Wuhan Mayor Hotline rose from 5,000 a day (the normal number) to more than 24,000. “During the 30 minutes after 12 a.m. on the 24th, we received more than 200 calls. Up until now, it hasn’t stopped. Calls keep coming in,” a manager at China Telecom said.

One woman, Qianqian, tried and failed to obtain help on behalf of her infected mother through all of the official channels. On January 24, Qianqian’s mother was in quarantine, and her family had all begun to show symptoms; no one could take care of her. That morning, Qianqian called every possible government agency she could think of. She called the mayor’s hotline, and when the call finally got through, she was told that her case would be reported to “the top.” She heard nothing. She then called the Wuhan Women’s Federation, where the single staff member on duty told Qianqian he did not know what to do either. She tried to called the Red Cross, but the line was constantly busy. Wuhan Health Commission told her that they did not have the authority to do anything about it. They encouraged her to call the mayor’s hotline.

During the first few days after the outbreak after January 20, all across the Chinese internet, from Weibo and WeChat to Douban — and even on the long-outdated QQ — people were crying out for help, explicitly appealing to civilians rather than the government. “As I was browsing Weibo, I thought the country had become an anarchic utopia established by NGOs and civil aid groups,” posted one netizen, @sorrywrongnumber. When the government did come up, it was often ridiculed.

The central regime unsurprisingly, wants to control the narrative surrounding the government’s fault in handling the virus. The State Council has created a WeChat mini program, encouraging individuals to submit any reports or suggestions about local government officials’ misdeeds (including slow reporting, cover ups, and inaction) directly to the central government. The idea is that central government representatives will then send special teams to investigate and “deal with” the reported local officials. The implication is clear: if officials are going down for this, they are not in Beijing.

The Party leadership’s intention to make local government leaders the scapegoat — which they arguably deserve — is also demonstrated by the fact that comments criticizing the Wuhan government (or other provincial governments) have survived censorship, whereas any criticism about either the system or the central government has been quickly deleted. For example, a Douban user (@mlln) posted a question asking, “How has this epidemic changed your perception of the country?”

The post received more than 200 responses before it was deleted less than an hour later. Answers were overwhelmingly pessimistic: “I began to feel it is shameful to live in a country like this,” @冬妮娅 posted. “My major is public health. If I had had any expectations for the elephant [in the room] before, and hoped to change the nation with my knowledge, now I am deeply disappointed. Nothing can save the people if the structural problems are not solved,” wrote @斯然如玉.

On WeChat, netizens were asked to rank the effectiveness of a series of institutions involved in handling the outbreak. The results, pictured to the left, show “medical staff at the frontline” ranked first, followed closely by the entire medical and health system and the national government. Netizens scored 7.18, and local authorities in Hubei and Wuhan scored the lowest.

On WeChat, netizens were asked to rank the effectiveness of a series of institutions involved in handling the outbreak. The results, pictured to the left, show “medical staff at the frontline” ranked first, followed closely by the entire medical and health system and the national government. Netizens scored 7.18, and local authorities in Hubei and Wuhan scored the lowest.

While the survey results are not necessarily an inaccurate reflection of respondents’ thoughts, the survey itself surely would have been deleted if the results were unfavorable to the central government. Generous praise of medical professionals at the front lines must come first, closely followed by high marks for central agencies. Perhaps most importantly, however, is the low ranking received by provincial authorities, who are poised to take most of the blame. A narrative that depends on the inefficacy of local leaders allows the same top-down Party stability mechanisms to carry on.

One of the most frequent complaints about the local government is their tendency to cover-up and downplay the epidemic’s severity, even as things were clearly getting out of control. Netizens responded to the Hubei governor’s claims via Weibo comments, including, “Here’s the governor fabricating rumors!”

Hu Xijin, editor-in-chief of Global Times, also criticized Hubei officials on January 25. “We should have predicted its risk, and we should have taken stronger actions earlier, but we just did not do enough. I personally think Wuhan Municipal Government and Ministry of Health have inescapable responsibilities [for this disaster].”

Conclusion

The coronavirus outbreak offers a potent example of what can go wrong within the current hyper-centralized CCP system. During the early period, maintaining stability was the essential political task, enacted seemingly instinctually by the local government officials who took minimal action and attempted to put on a show of carrying on as normal. But after January 21, when Xi Jinping gave his “important directive” and an anti-virus campaign began, controlling the spread of the virus became the new and most urgent political task. Politics first, humans second.

The paradox in Chinese society is that in order to help to the public, you have to admit they need help. But admitting a need for help might cause panic, threatening the mechanisms by which public outcry is mediated, which Dali Yang has called the “stability maintenance regime.” In this case, the officials had two conflicting directives: one, to maintain order and stability amid a crisis that might necessitate unfettered social media discourse in order to allow much-needed help to be sought. Second, to provide relief and care for the thousands of Chinese infected by the virus and millions of others worried about contracting it. Based on their waxing and waning action and inaction, officials on both the central and local level prioritized the first directive over the second: stability before safety.

During the five-day period where the state was clearly absent, the central government was trying to decide which way to go. Now, based on the tolerance of disparaging comments directed toward local officials who can serve as performative scapegoats (in stark opposition to the hasty censoring of any direct criticism toward the central government, which gets labeled a “rumor” and deleted) and the increasingly positive narrative being pushed on state media, it seems the central authorities have found a balance between acknowledgement and stability that they are comfortable with. It remains to be seen whether public health in Wuhan, China, and the rest of the world stands to benefit from the careful balance the Party has struck.

Johanna M. Costigan is a freelance journalist and an MSc candidate in Contemporary Chinese Studies at the University of Oxford.

Xu Xin is an MSc candidate in Contemporary Chineses Studies at the University of Oxford.