In line with Beijing’s economic and geopolitical agenda in Europe, the Western Balkans has seen an increased Chinese footprint, raising concerns in the West that in an era of great power competition, “the Balkans can easily become one of the chessboards where the big power game can be played.”

Despite the little viable market opportunities that the region offers to Chinese investors, the five Western Balkan countries (Albania, Bosnia and Hercegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia. Kosovo is excluded as not recognized) have been included since 2012 in the “16+1” platform (currently 17+1 with the addition of Greece) with East and Southeast Europe. Later, this regional platform became an integral part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and the Western Balkans were increasingly targeted for BRI-related projects as a result of their key strategic geographical position for the Balkan Silk Road, through infrastructure networks and logistical corridors between the Port of Piraeus (Beijing’s flagship project in the region) and markets in Western Europe. Beijing’s geo-economic and political interests aim to use the region as a gateway and transit commercial platform to Western Europe, where the real Chinese interests lie.

Western Balkans’ Infrastructure and Development Gap

Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Western Balkans lag significantly behind the EU in infrastructure and economic development. It represents a total regional population of less than 18 million and an average per capita gross domestic product of little more than $6,000, only 14 percent of the EU incomes ( $44,467).

Debt-burdened and cash-strapped, with unemployment rates at an average of 20 percent, the economies of the region are in desperate need for investment. The entire region taken together attracts less than 0.57 percent of the world foreign direct investment ($10 billion in 2018), despite its proximity with the EU, one of the most attractive markets in the global economy with 25 percent of global FDI, and at the same time one of the main investors in the world economy, with 30 percent of the investment.

The huge infrastructure deficits of the Western Balkans combined with the lack of capital, loose regulation practices, lax public procurement rules, and poor labor regulations appeal to Chinese investors looking to easily establish bases and invest in valuable assets in EU’s backyard.

Capital-rich and ready to outspend many Western actors in the region who are deterred by the questionable business environment of the region, Chinese companies, mainly state owned enterprises, maintain a visible advantage as they are supported by large government subsidies and state banks, and are willing to build at low costs without the stringent (and costly) requirements of meeting environmental and social standards.

Trade and Investment Patterns

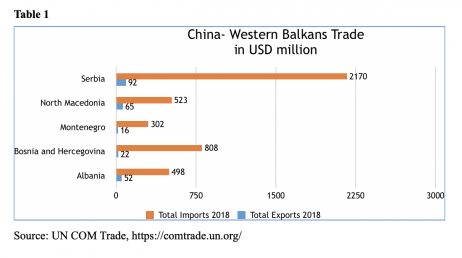

China´s share of trade with the Western Balkans is still very low, only $4.5 billion in 2018, accounting only accounting for only 5.5 percent of overall regional trade ($81 billion), where almost half of the trade goes with Serbia ($2.2 billion), China’s strategic partner in the region. Trade pattern are heavily tilted in favor of China, benefiting a positive balance with the region of $3.4 billion. To put it in the perspective, trade with the Western Balkans is only 4.3 percent of the China’s total trade with the “17+1” platform ($103 billion in 2018), according the UN COM Trade data.

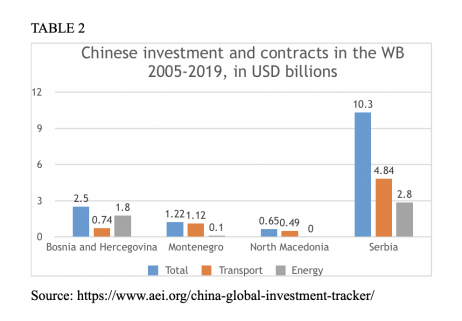

Chinese investments (greenfield investment and contracts) in the Western Balkans (without Albania) from 2005-2019 have reached $14.6 billion, Serbia leading with $10.3 billion, according to China Global Investment Tracker data of American Enterprise Institute. This would make up 20 percent of the total stock of the FDI in the region ($72 billion), according to UNCTAD. A misleading aspect of the analytical framework is that most of the money is not Foreign Direct Investment (actual investment), but loans. In fact, the main form of Chinese economic cooperation in the region is lending for infrastructure projects, mainly in transportation and energy, which are BRI-related projects. According to data form AEI, half of the Chinese money in the Western Balkans goes for transport and infrastructure public contracts financed by Chinese banks, precisely $7.2 billion. Other $4.7 billion go for investment in the energy sector, financed by loans. In sum, more than 80 percent of the total investment in the region is financed by loans.

Strong Signs of the “No Strings Mantra”

Beijing has used the narrative of the salutary effects of its BRI investments under the “win-win” mantra, but this narrative is belied by the economic realities of the region. The reality on the ground is very different. Economic cooperation is typified by the use of Chinese loans for infrastructure development, Chinese state owned enterprises, Chinese workers, and the spreading of Chinese labor and environmental standards, distinctly weaker than EU standards. Chinese implementing firms often profit from unsustainable deals, as sovereign guarantees shift risk onto host countries, at the expense of the financial stability in the region.

What the current Chinese-led infrastructure projects in the region have in common is the low estimate of financial and economic viability, with studies showing that construction costs would not be repaid in hundreds. Without rigorous financial evaluations and due diligence, some Western Balkan countries risk getting trapped in debt servitude to China. As of 2018, Montenegro (a new NATO member) owes almost 40 percent of its debt to China, followed by North Macedonia with 20 percent, Bosnia and Herzegovina with 14 percent, and Serbia with 12 percent.

Beijing’s Strategic Investments

Among the biggest projects in the region is the Belgrade-Budapest railway, financed for 85 percent ($2.5 billion) by China Export-Import Bank, and constructed by China Railway and Construction Corporation committed to its construction. In 2016, China’s state owned HBIS Group took over Smederevo’s steel mill for $55 million, which was sold from the U.S. Steel back to the Serbian government for the symbolic $1.

Serbia sees China as one of the major pillars of it foreign policy, not only economically, after the signature of a deal of $3 billion package of economic and military purchases. Belgrade is becoming an increasingly more important hub for China’s digital Silk Road as it aims to inherit the role of regional leader in digitalization and to become a focal point for future Huawei initiatives. In 2017, Huawei signed a contract with Belgrade to provide “Safe City” surveillance equipment to Serbian cities consisting of 1000 high-definition cameras in Belgrade alone and to establish the Huawei Innovation Center for Digital Transformation.

The new highway Bar-Boljare in Montenegro, connecting Belgrade with the port city of Bar, is financed for 85 percent of the estimated $1 billion (already increased to $1.1 billion) by China’s Exim Bank and being constructed by the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC).

In North Macedonia, the two highways are from Miladinovic to Shtip and from Kichevo to Ohrid, costing $580 million and implemented by Sinohydro Corporation LTD. In Bosnia and Hercegovina, Beijing has financed the national electric power company Elekropriveda with a $700 million loan from China’s Exim Bank to finish the thermal power plant in Tuzla, where three Chinese companies will be the implementers, while criticism has been raised from the EU that this will raise further pollution in the country.

In Albania, Chinese most important investments include Tirana National Airport acquired by China Everbright Group, a state backed financial firm, but also the most important oil producer refinery in the country (accounting for 95 percent of Albania’s crude oil), bought for $442 million from China’s Geo-Jade Petrolium Corp.

Beijing’s “Soft Power” in the Balkans

Governments in the Western Balkans continue to court Beijing for more investment, seen as a credible source of economic development and a reliable partner for infrastructure development. Chinese projects can easily be aligned with political cycles and when coupled with top-down, rather than transparent and market-driven procurement decisions, Beijing’s offer allows decision-makers in the region to fuel patronage networks and boost short term electoral advantages.

Political behavior also shapes public perception, which is shifting towards being more favorable to China. Few in the Balkans have an opinion on the domestic situation in China, and the geographical distance plays in Beijing’s favor. With the aim of building a community of friendly countries, Beijing is heavily investing in cultural diplomacy, from the Confucius Institutes present in every capital of the region, to chambers of commerce, and cultural centers.

The key driver of China’s clout in the region is by the appeal of its development model utilizing its capital as an “economic miracle-maker”, raising expectations and romanticizing about Beijing’s ability to bring wealth in the Western Balkans. This has raised some concerns in the western capitals fearing that through a deeper footprint, Beijing could become a “systemic rival” of the West promoting alternative forms of governance in countries with weaker institutions than the European Union’s.

Western Engagement in the Region

Contrary to the general misperception of Chinese “checkbook diplomacy”, the EU is the largest provider of assistance to the Western Balkans, and its combined funds for infrastructure and economic development are larger and cheaper. However, Beijing’ growing diplomatic and economic activism in the region has been aided by the skepticism on whether the EU can formulate a common position towards the Western Balkans.

The EU’s distraction to bring the Western Balkans closer to its institutional norms, values, and good governance standards, and the last decade of “enlargement fatigue” has created a perfect power vacuum, easily to be filled by new external players.

Not only the EU, but the West in general needs better options for the Western Balkans. In collaboration with the United States, the EU needs a clear strategy to develop economic opportunities in the Western Balkans built upon foundations of rule of law and good governance. As the main donors in the region, they should better leverage their investments, while enhancing and integrating strategic communication to ensure the public understands the purpose and benefit of the assistance.

The EU’s Europe-Asia Connectivity Strategy, published in late 2018, which aims to strengthen digital, transport, and energy links between Europe and Asia to promote development and provide alternatives to the BRI, includes the Western Balkans, but does not come with any funding attached. There is need for stronger synergies between EU assistance programs and U.S. initiatives, such as the U.S. Build Act of 2018, aimed at creating a new development financial institution with a $60 billion budget for investments in developing countries.

In an era of great power competition, stabilizing the Western Balkans and bringing them closer to transatlantic core values, norms, institutions, and democratic model of governance, should be a top priority for the EU and the United States. Western structural and infrastructure investments should also come with stronger conditionality for good governance and increased transparency, to improve the current regional business environment and achieve tangible change to attract the much needed serious foreign investment. The results of these efforts will prove to be good investments that will pay the positive dividends for generations to come.

Dr. Valbona Zeneli is the Chair of the Strategic Initiatives Department at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. The views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily represent views and opinions of the Department of Defense or the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies.