Since it first premiered in late February, the Thai television show “2gether: The Series” (“เพราะเราคู่กัน”) has been a hit both in Thailand and abroad, namely in mainland China. The romance drama revolves around two university students played by actors Metawin Opas-iamkajorn (“Win”) and Vachirawit Chiva-aree (“Bright”). Just last month, Chinese state media Global Times published a piece doting on the show, mentioning that it had garnered a 9.3/10 rating on popular Chinese review site Douban. The article went on to state how the show was “further improving cultural communication between China and Thailand.”

If recent online discourse is any indication, that comment has not aged very well.

The trouble started when the actor, Bright, liked a seemingly innocuous tweet from a Thai photographer containing four cityscape images, one of which was from Hong Kong. “These four pictures are taken from four countries,” the tweet said in Thai. Some Chinese fans took offense at the wording of the tweet because it referred to Hong Kong as a “country.”

It is not an uncommon scenario for outsiders operating in China, whether they be companies, actors, or fashion lines. The Chinese government does not take kindly to foreign firms contradicting the Party’s stance on geopolitical issues — especially those that concern human rights or territorial sovereignty. It is indeed “a minefield,” with Hong Kong, the South China Sea, Taiwan, Tiananmen Square, Tibet, and Xinjiang representing some of the most common pitfalls. Gap, the NBA, Marriott, McDonald’s, Delta Air Lines, Hong Kong actor Shawn Yue, Versace, and Zara are just some of the brands and personalities that have apologized or otherwise backtracked in some way following perceived gaffes on such topics.

So in an attempt to quell the online uproar, Bright issued an apology on Twitter over the apparent slip, promising that “there will be no mistake like this again.” The photographer also replaced the original tweet with a new version that swapped out “ประเทศ” (“country”) for “สถานที่” (“place”) while apologizing in both Thai and English.

At first, the apology seemed to work and pro-Beijing netizens appeared mollified. But with Bright and his contacts now under the microscope, the online confrontation escalated when the actor’s girlfriend, Weeraya Sukaram (“New”), who goes by “nnevvy” on social media, came under fire for retweeting a coronavirus-related conspiracy theory. Chinese netizens dug through New’s Instagram account to find a post from 2017 featuring a photo taken in Taiwan; in the comments on the since-deleted post, Bright said that New looked “as beautiful as a Chinese girl,” to which New asked “what?” In response to a question from a different user asking about her style, New responded to say it was that of a “Taiwanese girl.”

Chinese fans did not take kindly to these perceived slights, interpreting them as an affront to China’s territorial claim over Taiwan. From there, the online war-of-words quickly heated up; pro-Beijing trolls used the hashtag #nnevvy on both Twitter and Chinese equivalent Sina Weibo to demand an apology from the actor’s girlfriend, while also lobbing nationalistic insults at Thai users. Reuters reports the Twitter hashtag has generated more than 2 million tweets, while Global Times reports it has drawn 4.6 billion views from over 1.4 million posts on Weibo. A Facebook page compiling #nnevvy memes has already picked up more than 75,000 likes.

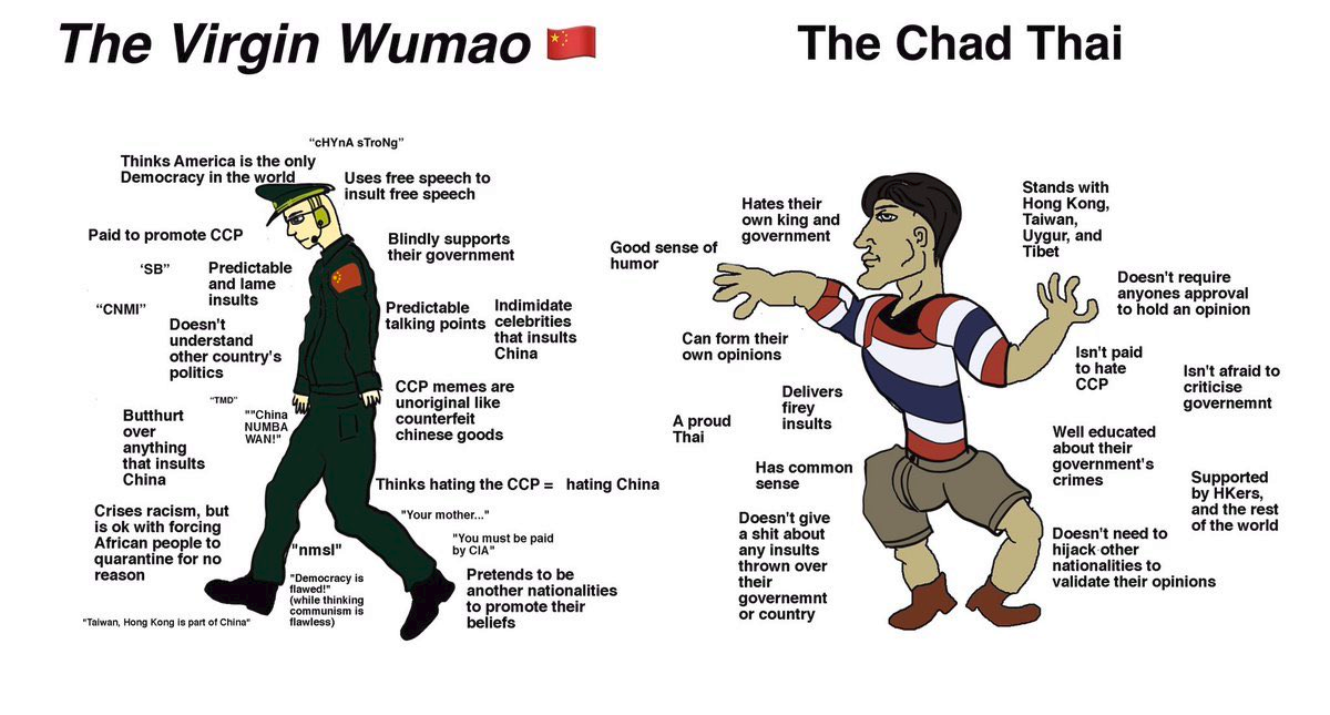

Much has been said about the threat to online discourse posed by Chinese internet trolls, whether they are “50 centers” (wumao) paid for their online antics or simply nationalistic citizens. But in this instance, it quickly became apparent that the insults lobbed by pro-China accounts weren’t quite landing as intended with Thai users; in fact, like rubber, the vitriol was bouncing right back. Thai users not only laughed at posts meant to insult them, but repackaged them into ever more clever memes — turning the tables on their would-be aggressors.

For example, the four-letter insult “nmsl” (Chinese shorthand for “your mother is dead”) was used so frequently that it became a recurring theme in retaliatory memes. When Chinese users tried to anger Thai users by insulting their government, Thai users basically nodded in agreement. Others poked fun at the closed nature of the internet in China, hinting that success on a heavily censored medium like Weibo would not translate to a more global platform like Twitter.

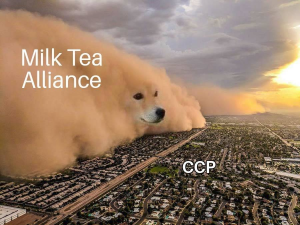

One of the online memes used to answer Chinese internet trolls’ attack on Bright, and later Thais in general.

Striking the perfect balance of wit, self deprecation, and zinging accuracy, many of the memes spoke to the political challenges Thailand has faced in recent years — the wavering status of the country’s democracy in particular, along with the waning legitimacy of the monarchy, previously viewed as a unifying force in times of political upheaval. The country has also seen Chinese influence steadily grow under the government of Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha, previously a military general who has ruled the country since 2014. Prayut came to power through a military coup before winning a contested (and long-delayed) election in March 2019. Combine the simmering frustrations of a lack of democracy, an unpopular and reckless king, and increasing coziness with China, add a pinch of humility, and you’ve got a recipe for, in this case, high quality memes.

While it’s not clear that Thai netizens necessarily needed assistance, they quickly found that they were not alone in their online battle with pro-Beijing trolls, as users from across Asia, including Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the Philippines came to their defense, offering solidarity in the form of encouraging words and (mostly) memes. On Twitter, Hong Kong democracy activist Joshua Wong voiced his support while colleague Nathan Law quipped it was “So funny watching the pro-CCP online army trying to attack Bright. They think every Thai person must be like them, who love Emperor Xi.” The mayor of Taoyuan, Taiwan, Cheng Wen-Tsan, included the #nnevvy hashtag in a tweet thanking “our friends from #Thailand,” noting the popularity of Thailand for Taiwanese tourists. “We look forward to increased exchanges after the #COVID19 outbreak!” the tweet says.

It’s common online knowledge that “feeding the trolls” of social media is naive at best and futile at worst; decisive victories are rare in the realm of internet arguments, and someone will always be “wrong.” But with #nnevvy, we see a glimpse of the internet’s unifying potential — what many thought a new, connected world might offer before bots, misinformation, and media manipulation took over. Individual users from across four Asian democracies — some flourishing, some fragile — united against a common, familiar adversary. And so the #MilkTeaAlliance was born.

On April 12, Global Times posted a new article about the Thai drama “2gether,” stating that the show “is experiencing a backlash in China” over the incident. The article mentioned that Bright’s follower count on Sina Weibo has taken a hit, while the show’s rating on Douban has dropped from 9.3 to 9.0, where it stands as of writing. Noticeably absent from the Global Times piece was any mention of the memes that have defined the #nnevvy episode. Then, two days later, just as the dust seemed to have settled, the Chinese Embassy in Bangkok published a lengthy statement on Facebook to address the controversy, saying in part: “The recent online noises only reflect bias and ignorance of its maker, which does not in any way represent the standing stance of the Thai government nor the mainstream public opinion of the Thai People.” The statement also reiterates China’s “One China principle” as well as the “ancient” China-Thailand friendship. The post has garnered nearly 20,000 comments and counting — many pushing back against the statement while affirming the newfound ironclad commitment of the Milk Tea Alliance.

The #nnevvy meme war and the online alliance born from it may seem trivial in the grand scheme of things, but as James Griffiths points out for CNN, the online actions of pro-CCP keyboard warriors can create “real world” issues for the Party: “On issues such as pollution, corruption and food safety, public opinion has had a notable effect on government policy, even as the censors worked to ensure that people did not escalate their online dissatisfaction to offline protests.” Over the past several days, the #MilkTeaAlliance has been tackling a new issue, one that is very much based in the real world: China’s damming of the Mekong River.

In a coincidence of timing, new research released this week by water-focused Eyes on Earth found that China was directly responsible for record droughts experienced across the lower Mekong region last year. That’s thanks to Beijing’s control over the upper Mekong and Tibetan plateau, where the river originates. The findings, which the Chinese government disputes, show that the downstream droughts occurred despite “higher-than-average water levels upstream,” Reuters reports. Many of the top tweets for #MilkTeaAlliance now also include the hashtag #StopMekongDam. It remains to be seen whether the Alliance will consider making room for new members, such as those from countries where the Mekong is so essential: Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam, in addition to Thailand. But it’s clear that they too have common ground to stand on, as well as a shared adversary. What’s less clear is what real world impact their online advocacy might yield.

Chinese netizens hopped the country’s Great Firewall to defend CCP-endorsed political views and push back against perceived critics, but found that rhetorical attacks rooted in patriotism and nationalism offered weak ammunition in the face of a self-aware citizenry that doesn’t conflate personal identity with that of their nation. Thai netizens co-opted the #nnevvy meme and wound up inspiring a new citizen-led transnational partnership in the Milk Tea Alliance, offering an interesting and perhaps unprecedented chapter in online transnational discourse. While Milk Tea Alliance members may be separated by thousands of kilometers in physical distance, they’re also as connected as the closest keyboard. Plus, as a popular accompanying Thai hashtag makes clear, “milk tea is thicker than blood.”

Dan McDevitt is a researcher focusing on technology and human rights, and Internet censorship in particular. He holds a master’s in international relations from American University and is based in Denver, CO. You can follow him on Twitter @dmcdev.