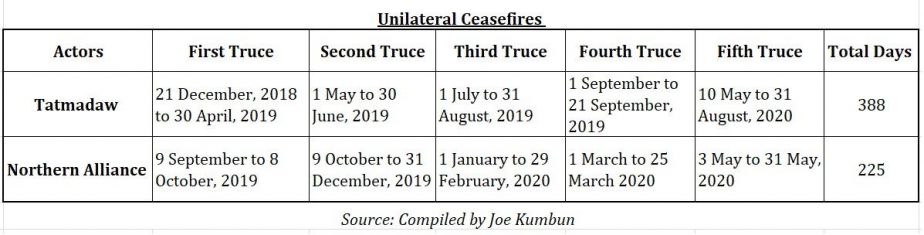

In Myanmar, unilateral ceasefires have been interchangeably announced by the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw) and a group of ethnic armed groups – known as the Northern Alliance – composed of the Arakan Army (AA), Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), and Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA). The first unilateral ceasefire was announced by Tatmadaw on December 21, 2018. The Northern Alliance followed by announcing their first truce on September 9, 2019, after the Tatmadaw extended the truce for a third time. Both sides have announced unilateral ceasefires five times so far (See the table below).

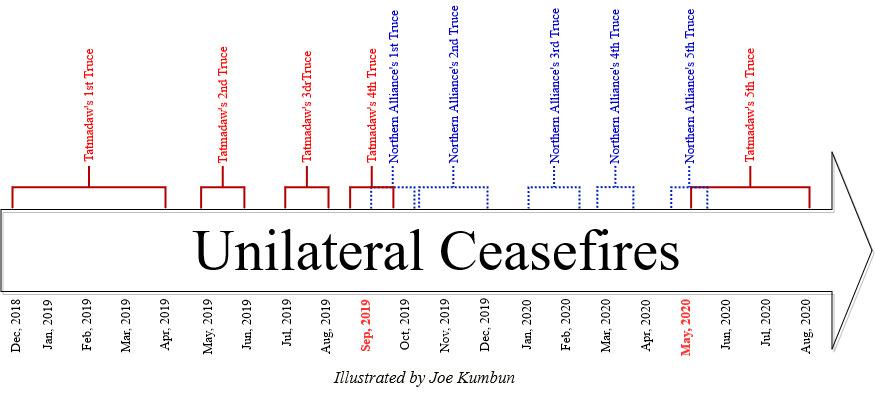

The unilateral ceasefires of both parties look to cover plenty of days as they announced them at different times. However, the simultaneous ceasefires, covering both sides, are limited in duration. The total length of simultaneous ceasefires – in September 2019 and May 2020 – is only 33 days. (See the illustration below).

But even during the unilateral ceasefire periods, the Tatmadaw and Northern Alliance could not managed to lessen or stop the fighting. Instead, tit-for-tat fighting raged on in Shan, Chin, and Rakhine states.

Although the country is grappling with the global coronavirus pandemic, the fighting between the Tatmadaw and AA in Chin and Rakhine states continues and has produced thousands of displaced persons.

In addition to the AA, the Tatmadaw has clashed with the Karen National Union (KNU) that signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) in October 2015.

In spite of the fact that the unilateral ceasefires appear to have been aimed at reaching bilateral ceasefire agreements through negotiations, just only three talks – one in Muse and two meetings in Kengtung, Shan state last year – managed to happen. After the last meeting in September, the next meeting was scheduled to be held in October last year; the talk did not happen. The sides met at an informal meeting in January 2020 in China’s Yunnan province and agreed to resume the stalled formal talks in mid-February. Unfortunately, the meeting did not happen because the Chinese government – the facilitator of the talks – had to grapple with the outbreak of the coronavirus.

The unilateral ceasefire per se seems meaningless as it has not stopped or even lessened the fighting so far. It is only a starting point for negotiations. Only bilateral ceasefire agreements can cease the escalation of fighting in Rakhine state and beyond. Undeniably, reaching bilateral ceasefire agreements is indispensable to move toward peace.

The Tatmadaw and the ethnic armed groups should not waste the moment and opportunity presented after they reached agreement on seven points in the last meeting in Kengtung. The seven points they agreed on are: 1) to discuss ceasing armed conflict and signing a bilateral ceasefire agreement; 2) to tackle the internally displaced persons (IDPs) issue; 3) to set ceasefire rules; 4) to establish communication offices to avoid further clashes; 5) to avoid making arrests on both sides to build mutual trust; 6) to discuss the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) process; and 7) to discuss establishing a mechanism for conflict resolution.

The Tatmadaw has recently deployed its COVID-19 diplomacy toward ethnic armed groups by sending special conveys to different ethnic armed organizations. Maj. General Khun Thant Zaw Htoo from the office of the commander-in-chief visited the quarantine center of the Kachin Independence Organization/Army (KIO/A) and delivered 59 packages of protective equipment, such as surgical masks, N95 masks, face shields, and other personal protective equipment, as well as food. Similarly, the Tatmadaw’s commander of the South Eastern Command delivered protective equipment to the KNU, KNU/KNLA Peace Council, and DKBA-Klohtoobaw Karen Organization (KKO), and the commander of the Eastern Central Command provided equipment to the Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army and Karenni National Progressive Party. Yet the Tatmadaw has not sent any delegation to the Northern Alliance.

Tatmadaw’s recent diplomatic moves will be conducive to build the trust with the groups, the KIO in particular. The fact is that the KIO, in conjunction with the Northern Alliance, is seeking to reach a bilateral ceasefire agreement with the Tatmadaw.

It is understandable that all parties have to focus on combating the common enemy, COVID-19, but the Tatmadaw and the Northern Alliance plus KIO should seek to resume the stalled talks so as to reach bilateral ceasefire agreements. They should push themselves to lay out the tentative framework for practical and effective negotiation.

Absent such concerted efforts, a prime opportunity will be lost and the potential to reach bilateral ceasefire agreements will be elusive. If so, the hope for “eternal peace” in 2020, promised by Tatmadaw Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, will fade away.

Joe Kumbun is Political Analyst from Kachin State, Myanmar.