In early March, just as the COVID-19 pandemic forced governments across the world to close borders and shut down economic activity, the Chinese Global Times reported that the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) had edged over the European Union to become China’s largest trading partner. According to the newspaper, the increase in trade was a testimony to the “unbreakable supply chain with China” and robustness of linkages with Southeast Asian economies.

To an extent, such news comes as no surprise. Over the past year, the 10 Southeast Asian economies that comprise ASEAN have been among the main beneficiaries of the ongoing U.S.-China trade war, with many foreign companies already relocating to the region from China. But the Global Times’ triumphant reporting on the strong connection between China and ASEAN makes yet another proposition plausible: Given the current geopolitical turmoil and predictions of imminent global decoupling between China and the United States, could it be that Beijing’s continued bid for global interdependence is only as good as the Southeast Asian countries’ willingness to play a part? In other words, at the present juncture, and with the growing international backlash against Beijing, could it be that China needs the countries in Southeast Asia – not only as an economic partner, but also as the (sole) champion of China’s vision to “work together to build a community with shared future”?

Such questions certainly present a notably different scenario from the typical calculus on globalization and political alliances. In the world of grand geopolitical narratives, the countries of Southeast Asia usually feature as a relatively minor player. At most, they are expected to either balance skillfully between China and the United States, or edge closer to one or the other superpower. Southeast Asia was certainly not a major consideration for the Chinese government at the start of 2020. Remember that, for China, 2020 was planned to be the year of great collaborations, especially with members of the European Union. Beijing had already made strides in this direction the year before: by signing a Belt and Road agreement with Italy; continuing engagement with the countries in East and Central Europe; and, swiftly and effortlessly changing the original “16+1” alliance to “17+1” by adding Greece. In addition, a unique, “first-ever” high level meeting was planned in Germany in September 2020. A plethora of collaboration options seemed possible, even with the United States. Most prominently, despite trade tensions throughout 2019, in early January the two governments signed a Phase One trade deal.

By June 2020, however, all of this is already the distant past amid signs of what might become a fundamental shift in global sentiments in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Whereas only a few months ago an understanding of an interconnected world was taken for granted, now the very idea is met with skepticism. To put it differently, in addition to its devastating social, economic, and political effects, the COVID-19 pandemic is redrafting interdependence narratives and weaponizing arguments against connectivity and globalization. In addition, even outside of prospects for U.S.-China decoupling, now further exacerbated by the pandemic, there are increasing calls for ending reliance on China-dominated global supply chains and talk of self-reliance. At the time of writing, any traces of potential collaboration with the United States have vanished and, with the upcoming U.S. election, many foresee further escalation of the bellicose language coming from Washington. There are similarly dark clouds over the partnership prospects between China and members of the European Union: Talks with Germany are still scheduled for September, but already the commentary is that the tone and emphasis are somewhat changed. Despite all the Chinese government goodwill in dispatching medical teams and aid to virus-stricken European countries throughout March and April, the EU governments have yet to overcome their suspicions of Beijing’s “mask diplomacy.” There are cracks even in the “17+1” alliance. To top all of this off, Beijing’s unleashing of “wolf warrior” diplomats to defend the Chinese government’s initial response to the pandemic and extol the virtues of the Chinese political system has largely backfired – even according to China’s own leading experts.

But perhaps the strongest signal of a potentially shifting balance on alliances and partnerships came from the initial response to the virus. In contrast to the United States and EU, countries in Southeast Asia were quick to collaborate with China from the very start of the COVID-19 crisis, swiftly organizing an ASEAN-China Foreign Ministers Summit in February. Crisis solidarity and joint response did not stop there. In the early days of infection, while anti-Chinese sentiment was brewing across the world, Southeast Asian countries responded to news from Wuhan with compassion, solidarity, and unwavering support. Reportedly, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, and Singapore all donated various types of medical equipment. A Thai artist even composed a song in solidarity with Wuhan. To reciprocate, once the virus started spreading outside its borders, China sent medical aid and experts to the Southeast Asian region. These multiple levels of coordinated China-ASEAN response showcased both the necessity and benefits of interdependence and cooperation in times of crisis. In addition, they presented a stark contrast to the initial reactions from the rest of the world, and, most prominently, the lack of any support from the European Union to Italy in the early March crisis.

Where does this leave Beijing’s vision for globalization and interdependence to date? On the one hand, there are China’s botched prospects for deepening engagement with key European partners, continued animosities with the United States, and questionable diplomacy practices. On the other, in dramatic contrast, there are the strong economic ties and close coordination and solidarity with ASEAN countries on the COVID-19 pandemic response. It is this conjuncture that presents an entirely unexpected proposition: For Beijing, fulfilling the vision of interdependence could very well require a continued show of unity and solidarity with the countries of Southeast Asia as a key regional and global partner. Conversely, for Southeast Asia, this presents an unique opportunity to take China’s vision for a globalized world at face value. In other words, countries of Southeast Asia have the rare chance to leverage Beijing’s language of interdependence and multilateralism in addressing pressing issues, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and South China Sea. Here are some initial considerations on both.

The Belt and Road

Interdependence could be key to the future feasibility of the BRI. With the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been multiple voices questioning the continued viability and sustainability of the flagship Chinese initiative. In addition to the global economic shutdown, multiple BRI infrastructure projects across the globe have been directly impacted by reduced manpower due to border closures.

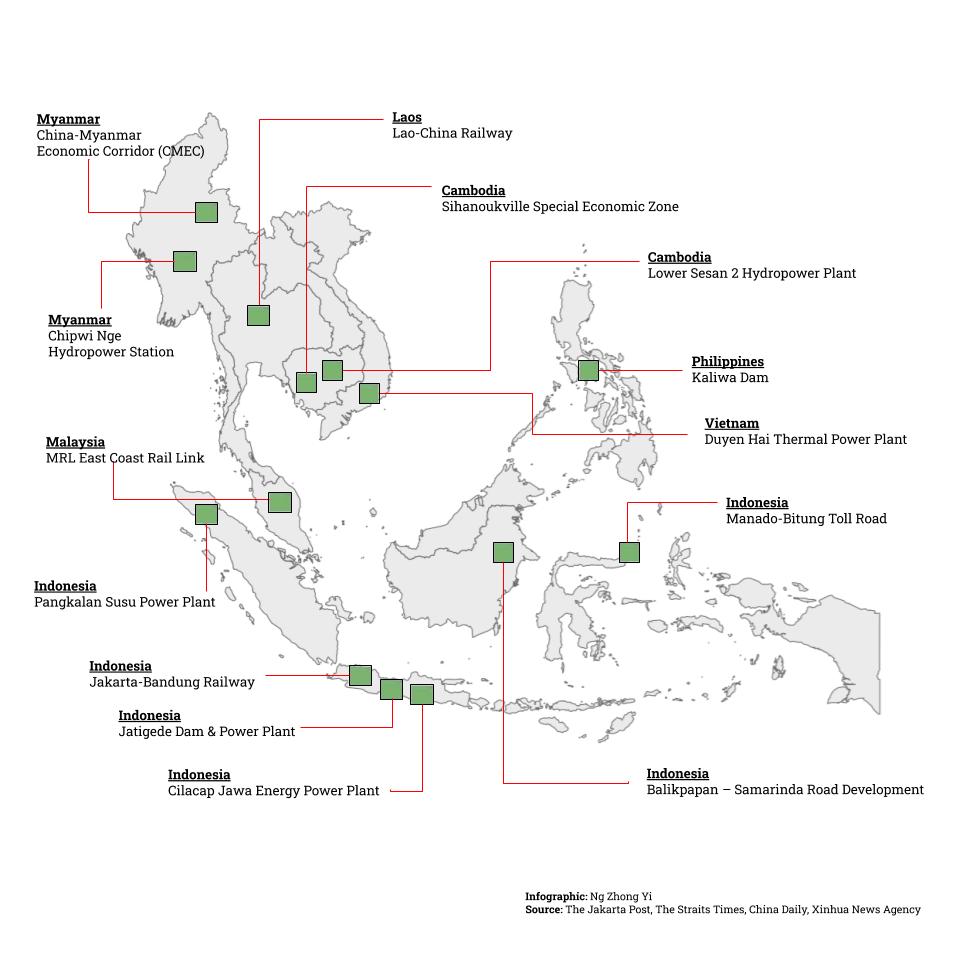

In Southeast Asia, information on any ongoing infrastructure projects is scant. This is despite the fact that there are multiple engagements, with 2018 figures showing well over $740 billion in total BRI investment in Southeast Asia. Presently, based on research of Chinese and local news media sources, only 13 projects have been identified as operational (see Figure 1), A very small fraction of the region’s total, these projects are the only ones to have reported varying degrees of operational capacity, temporary suspensions, and/or extended deadlines for completion of planned construction.

Certainly, the BRI infrastructure projects are not the only ones affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and suspensions and delays could be the result of multiple challenges. However, at least one issue associated with the current conundrum, presents a unique opportunity: In the spirit of collaboration, and by leveraging the present conjuncture of closed borders and quarantine immobility, Southeast Asian countries could (re)negotiate the hire of local manpower at BRI project sites. Incidentally, the benefits of such a proposition could go well beyond the critical need for resuming and sustaining project operations. Prior to the COVID pandemic, BRI infrastructure projects have been repeatedly criticized for the almost exclusive use of Chinese workers. On the ground, this usually translates into few or no opportunities for the recruitment of local staff and no possibility for substantive local involvement in various operational and technical aspects of the projects. There is therefore limited possibility for local capacity building or for multifaceted integration between personnel associated with the project and local communities. In a larger context, this phenomenon also showcases a failure to deliver on the overarching BRI initiative objectives, i.e. building the much-touted “community with shared future,” “win-win” scenarios, and “people to people connections.”

(Re)negotiating local involvement could have multiple advantages beyond overturning the economic losses of the present shutdown. Increasing the numbers of local hires would be a major way to enhance local involvement. Equally as important, this would also turn the language of interdependence from a propaganda slogan into an actionable strategy.

The South China Sea

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, China has engaged in multiple initiatives to showcase its commitment to globalization, interdependence, and multilateralism. Most prominent among these have been its worldwide medical assistance and unwavering support for the WHO. Yet, the South China Sea disputes present a major exception to China’s globalization agenda.

Beijing’s sovereignty claims and insistence on special rights within a “nine-dash line” encompassing nearly all of the South China Sea have once again generated tensions within the region and also led to an increased U.S. Navy presence in the area. China has also undermined the authority and credibility of international arbiters with its now-notorious rejection of the 2016 landmark UNCLOS ruling in favor of the Philippines against China. Certainly, the “nine dash line” itself is problematic because it crosses areas considered exclusive to the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam, and Indonesia (the Natuna Islands). And while China is not the only one to have made controversial claims in the area, the most recent Chinese government announcement on the naming of 25 islands and reefs as well as 55 undersea geographic entities in the South China Sea is the latest in a series of controversial maritime engagements in the region over the years.

There are, however, many signs that Beijing is fully aware of the need to develop a common understanding with its neighbors on the issue of the South China Sea. For example, one of the latest attempts at show of unity was the release of the now-infamous “One Sea” song by the Chinese Embassy in the Philippines. The song was meant to celebrate the solidarity between Filipino and Chinese frontline workers in addressing the COVID-19 crisis. Lyrics such as “because of your love that flows like waves hand in hand, we move to a bright future, you and I are in one sea” were meant to be suggestive of the two countries’ interdependence and unity. Yet the strategy backfired. The song has been vehemently criticized by netizens as a propaganda attempt, with many challenging the meanings and intentions behind the language and concept of “one sea.” Certainly, the types of sentiments expressed by netizens can hardly be brought up at official meetings, such as the now-postponed ASEAN-China Code of Conduct negotiations on the South China Sea. But, to those paying attention, criticisms of the song clearly showcase the limits of China’s purported language of commonality and unity.

Ultimately, the “One Sea” incident also suggests that finding a compatible language is very much at the center of any South China Sea negotiations. In particular, whereas the language of both international law (the 2016 UNCLOS resolution) and cultural propaganda (the “One Sea” song) have been deemed unacceptable, claims that adhere to common notions and norms could become the basis for a different appreciation and understanding of a joint maritime space. For example, China’s objections to the 2016 UNCLOS resolution, could be used by others as a cue to formulate similar language and claims for “historic rights” and traditions — especially by building on the now re-emerging narratives of maritime connectivity and by showcasing the critical historical presence of multiple local communities in the region. For example, Beijing enthusiastically endorsed the Indonesian Global Maritime Fulcrum strategy, and even sought to link it to the BRI.

Conclusion

With geopolitical and economic pressures exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, countries in Southeast Asia now have the unique opportunity to actively shape a new type of relationship with China: one that is not based on dependence, but instead leverages China’s proposed language of interdependence. Certainly, it is never an easy task to engage China on equal terms. Nevertheless, as Beijing strives to become the leading proponent of multilateralism in the post-COVID world, the parameters and rules of interdependence need not be shaped by China alone. Here, Beijing’s ability to engage with its regional partners can serve as a litmus test to the possibilities and limits of the much-touted vision to “build a community with a shared future.” For such a vision is only as good as the willingness of others to endorse and implement it.

Marina Kaneti is Assistant Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore. She specializes in topics of global development.