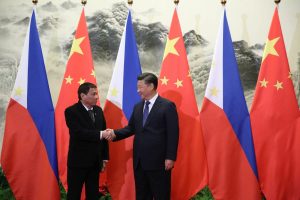

When the Filipino people elected Rodrigo Duterte to become their next president in May 2016, China saw a distinct opportunity to pull the longtime U.S. ally away from Washington and into Beijing’s strategic orbit. Avowedly anti-American, President Duterte on his first trip to Beijing in October 2016 exclaimed that it was “time to say goodbye to Washington” — much to the delight of his host, Chinese President Xi Jinping, and other Chinese leaders.

In subsequent years, China pledged to invest in the Philippines through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and to cooperate on achieving “joint exploration” of disputed waters in the South China Sea. However, Filipino mismanagement of the BRI and the inability of the two sides to see past their sovereignty disputes to conduct joint exploration left question marks hanging over the direction of bilateral ties. Then came an enormous geopolitical boost for China on February 11, 2020. On that day, Duterte decided to terminate the U.S.-Philippines Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA). The VFA enables, among other things, U.S. troops to freely enter and move around the country in support of a variety of military missions, including to deter and fight China in the South China Sea.

Duterte’s decision was hailed by Beijing as evidence the United States was losing the great power competition with China in the Indo-Pacific. A Chinese state-run media headline exclaimed, “Washington’s divisive intents get cold shoulder,” and another called Duterte’s decision a “severe blow” to the U.S.-Philippines alliance. One of China’s military outlets further argued that Duterte’s announcement underscored a “deep bilateral feud” that, according to Beijing’s hardline tabloid Global Times, would “upset U.S. meddling in the South China Sea.”

The problem for Beijing was what happened on June 2: Duterte and his government decided to postpone VFA termination, breathing new life into the agreement. To be sure, Chinese policymakers privately may never have fully believed the VFA would end. For example, according to Dai Fan, director of the Center for Philippines Studies at Jinan University, “This week’s [June 2] reversal does not surprise us. However, we just did not expect to happen so soon…China still has a long way to go in replacing the U.S. in this region.” Indeed, as I have argued previously, there were many good reasons to be suspicious of the commonly held view that Duterte would never reverse course on VFA termination because of his anti-American stance.

Nevertheless, the reasons cited by Filipino Secretary of Foreign Affairs Teddy Locsin Jr. for the reversal — “heightened superpower competition” and, interrelatedly, the COVID-19 pandemic — must be disconcerting for Beijing. This probably means that since Duterte’s announcement of VFA termination on February 11, Manila has not felt secure with Chinese behavior and therefore needs to keep the United States engaged in the region. As I have contended in these pages, Beijing appears to have missed a monumental opportunity to pull the Philippines away from the U.S. once and for all.

But to its credit, Beijing has refused to quit waging great power competition against the United States in the Philippines. Fortuitously, the 45th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic ties between China and the Philippines was just a few days after Duterte’s VFA decision, on June 9, and gave Beijing the opportunity to shift the narrative. In a string of articles, including an op-ed from the Chinese ambassador in the Philippines, Beijing touted the vitality of relations. In an exchange between leaders, Xi noted “I attach great importance to the development of China-Philippines ties,” and Duterte added that China was a “close neighbor and a valued friend.”

Most recently, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s announcement on July 13 that the United States would shift South China Sea policy and recognize the legitimacy of maritime counterclaimants’ sea claims, including Manila’s maritime claims settled under an international arbitral tribunal ruling in 2016, led Chinese Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi to urgently contact Locsin the next day. According to a Chinese readout, Wang and Locsin in their discussion underscored that “President Rodrigo Duterte made an important political decision to reverse the confrontational policy pursued in previous years,” and that “…the United States does not want to see peace in the South China Sea…” Wang and Locsin further noted that “with its latest ‘statement,’ the U.S. openly reneged on its commitment of not taking sides on disputes over the South China Sea.”

Then, on July 20, the China’s top diplomat in the Philippines, Ambassador Huang Xilian, added, “While China and ASEAN countries [are] working very hard on managing the South China Sea issue, we have to be on high alert that the United States as an external force has also been intensifying its meddling in the South China Sea.”

China’s bottom line has been to reaffirm progress made in bilateral relations since Duterte’s election in an attempt to prevent a further erosion of its position vis-à-vis the United States because of the favorable shift in Washington’s South China Sea policy. Indeed, Chinese concerns are warranted as Filipino Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana on July 14 responded favorably to Pompeo’s speech, emphasizing that Beijing must “abide by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas [UNCLOS].” The day before Pompeo’s statement, on July 12, and in celebration of the four year anniversary of the arbitration ruling, Locsin himself also said the issue was “non-negotiable.”

For its part, the United States is not backing down either. In an op-ed timed to run after Pompeo’s speech, U.S. Ambassador Sung Kim wrote that “Beijing’s harassment of Philippine fisheries and offshore energy development within those areas is unlawful, as are any unilateral PRC [People’s Republic of China] actions to exploit those resources.” Washington is also almost certainly working with Manila to convince it to make its reversal on VFA termination permanent in the coming months.

It remains to be seen how the long-term geopolitical competition between the U.S. and China over the Philippines will play out. But one thing is for certain: China, in spite of Duterte’s VFA reversal, is likely to continue seeing opportunity to disrupt and potentially even divide the U.S.-Philippines alliance. Beijing will only be emboldened to pursue this course with Duterte in office, who has demonstrated not only anti-American, but also pro-China proclivities. Thus, the United States along with its other allies and partners should not expect China to back down anytime between now and the end of Duterte’s tenure in 2022, which is likely to make this period particularly turbulent.

Derek Grossman is a senior defense analyst at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation, an adjunct professor at the University of Southern California, and a regular contributor to The Diplomat. He formerly served as the daily intelligence briefer to the assistant secretary of defense for Asian and Pacific security affairs at the Pentagon.