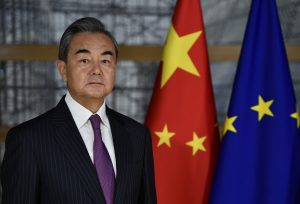

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi will visit Europe this week, his first trip abroad since the COVID-19 pandemic gripped the world. He will be traveling to Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, France, and Germany from August 25 to September 1, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced.

Wang has not been abroad since February, when he attended an “emergency meeting” on the coronavirus outbreak with his ASEAN counterparts in Laos. The choice of Europe as China’s return to some form of a diplomatic normal thus is striking. Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian told reporters on Monday that Wang’s trip shows “the importance attached to China-European relations by both sides.”

“As COVID-19 adds to the instability and uncertainties in the international landscape, it is of even greater significance for China and Europe, two major forces, markets and civilizations in the world, to work together on strengthening international solidarity against the pandemic, upholding multilateralism, and jumpstarting the world economy,” Zhao added.

While the spokesperson was nothing but upbeat about the prospects of China-Europe cooperation, the visit comes amid a significant hardening of European positions on China. COVID-19 has not helped China’s image in Europe, especially after its highly publicized efforts at “mask diplomacy” rubbed many Europeans (including EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell) the wrong way. Beyond that, concerns over the rights situation in China, especially Xinjiang and Hong Kong, are growing impossible to ignore. And as Philippe Le Corre and John Ferguson noted in a recent Diplomat article, both the U.K. and France have soured on Huawei, issuing de facto (albeit future) bans on use of the Chinese telecommunication firm’s equipment in 5G networks.

Even in Central and Eastern Europe, often painted as China’s “bridge to Europe” (or, less charitably, China’s “Trojan horse”), relations are far from rosy. As Andreea Brînză noted in a recent article for The Diplomat, from the perspective of the CEE countries, the grand promises of the 17+1 (formerly 16+1) platform has turned out to be “largely a disappointment.” Domestic political changes in Czechia (also known as the Czech Republic) and Slovenia have made both those countries noticeably more critical of China’s rights record.

It’s telling that this time, Wang is focusing solely on Western Europe in his upcoming tour. The CEE bloc apparently did not merit a stop; instead, the Hungarian foreign minister will meet with Wang briefly on August 24, the day before the Chinese foreign minister departs for Italy.

For China, Western Europe takes on a critical importance amid souring ties with the United States. With each day seemingly bringing a new action against China from Washington, Beijing will be keen to avoid Western Europe joining the pile-on. Each of Wang’s goals in the trip, as summarized by Zhao, can be read in this light (my comments in brackets):

Through this visit, China hopes to achieve three goals: that the two sides will act on Chinese and European leaders’ consensus and advance major political and economic agenda [i.e., provide China some diplomatic options as U.S. ties go south]; deepen cooperation on fighting the virus and keeping the global industrial and supply chains stable, and further discuss cooperation in emerging sectors like digital economy and green economy [i.e. secure China some breathing room for the relentless calls for “decoupling” emanating from Washington]; send out the message of jointly upholding multilateralism and improving global governance and contribute more to world peace, stability and development [i.e., framing the U.S. as the deviant actor and China as the upholder of global norms Europe should partner with].

Since the Trump administration, with its defiant aversion to multilateral fora and even longstanding U.S. alliances, took power, China has been framing itself as a champion of the multilateral order – and looking to find common cause with Europe to that end. Wang struck many of these same notes in his speech at the Munch Security Conference on February 15 (his second-to-last trip abroad before the long COVID-19 hiatus). But that messaging has become less and less persuasive as Europe registers its own concerns over everything from China’s trading practices to rights violations.

Originally, 2020 was supposed to be a banner year for China-Europe cooperation. There were plans for a historic meeting between China’s Xi Jinping and the leaders of all the EU member states in Germany in September. That summit has since been cancelled – ostensibly because of the pandemic, but there are persistent reports that European leaders were less than pleased with the lack of progress on a long-desired bilateral investment treaty.

As a sign of the growing disagreement, the most recent China-EU summit (held virtually) did not result in a joint statement. The EU press release reflected Europe’s changing view: while both European Council President Charles Michel and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen recognized the importance of partnership with China, they also voiced serious concerns about the relationship.

Theresa Fallon, founder and director of the Centre for Russia Europe Asia Studies (CREAS) in Brussels, has much more from that summit, the dropped September summit, and China-Europe relations writ large in the upcoming September cover story of The Diplomat Magazine. In the meantime, Wang’s tour of Western Europe, and the comments from his hosts after those meetings, are well worth watching for an update on the state of China’s image in Europe.