Each year, thousands of visitors to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum can view two paper cranes, which represent a symbol of peace in Japan, provided by former U.S. President Barack Obama during his 2016 landmark visit to Hiroshima. Unfortunately, these cranes were not accompanied by an apology from Obama for the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In fact, all American presidents have refused to apologize for the bombings, which occurred 75 years ago. This refusal is motivated by the hegemonic narrative in the United States regarding the atomic bombings and widespread public opposition to an apology and commemorating Japanese victims. This unwillingness to apologize is also likely motivated by the fact that an apology may bolster international demands for the U.S. government to provide compensation to all individuals affected by U.S. nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands during the Cold War.

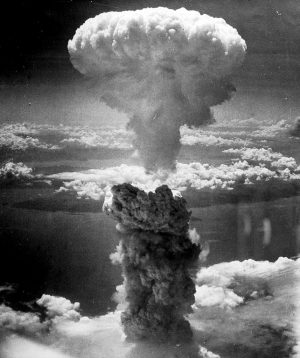

On August 6, 1945, the U.S. Army Air Forces dropped an atomic bomb dubbed “Little Boy” on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, killing thousands of civilians instantly. By the end of 1945, 140,000 people, predominantly Japanese, but also a sizable number of Koreans, had died from injuries, radiation sickness, and burns resulting from the bombing. On August 9, the United States dropped the so-called “Fat Man” atomic bomb on the city of Nagasaki, due to clouds blocking visibility of the original target city, Kokura. The bomb, which landed in a predominantly civilian area, immediately killed thousands and by December 1945, 90,000 people living in Nagasaki — the majority of whom were Japanese — had died due to the bombing. Some Koreans, many of whom were working as forced laborers in Nagasaki at the time of the bombing, were also killed.

Hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) have faced ongoing psychological trauma, discrimination and increased risk of radiation-related illnesses, notably cancer. In some cases, women who were pregnant and living in Hiroshima or Nagasaki at the time of the bombings gave birth to babies with disabilities, thus indicating the intergenerational consequences of the use of nuclear weapons.

Some hibakusha have advocated in favor of the U.S. government apologizing for the bombings. Despite this, successive U.S. presidents have refused to apologize and have argued that the bombings were justified and necessary.

For example, in 1995, then President Bill Clinton stated that the United States “owes no apology to Japan” for the atomic bombings and argued that the “atomic bomb had ended the war.” This statement represented an attempt to justify the mass killing of civilians and the perpetration of war crimes by the U.S.

Similarly, in 1992, Clinton’s predecessor, George H.W. Bush, asserted that the decision to drop the atomic bombs “was right… because it spared millions of American lives.” Furthermore, in 1985, then President Ronald Reagan claimed that the atomic bombings “saved” “more than one million American lives.” These attempts to justify the bombings on the grounds of saving Americans lives are not new, rather, they have been mounted by U.S. politicians since the 1940s.

Moreover, in 1991, in relation to the atomic bombings, Bush also publicly made the offensive and inappropriate comment “hey let’s forget that, let’s [the U.S. and Japan] go forward now together.”

Attempts by U.S. presidents to justify the bombings and frame them as necessary are unsurprising as they mirror the hegemonic narrative in the United States regarding the bombings, which is embedded in the American education system. Many American schoolchildren are taught that the bombings were necessary to avert the U.S. invasion of Japan and thus prevent the deaths of American service people. Many school textbooks also promote the argument that the bombings ended World War II.

This dominant narrative is problematic. It depicts a U.S. invasion of Japan as an inevitable consequence of not dropping the atomic bombings, when, in reality, there were other options available to the U.S. government, including, but not limited to, continuing the economic blockade or commencing formal negotiations with the Japanese government. Furthermore, as historians have highlighted, the notion that dropping the atomic bombs caused the end of World War II is questionable.

Regardless, the dominant narrative that the bombings were necessary and justified in part explains why U.S. governments refuse to apologize for the bombings.

Similarly, U.S. governments have also declined to apologize due to widespread public opposition to an apology. According to a 1995 Gallup poll, over 70 percent of Americans opposed the U.S. apologizing for the bombings. A 2015 Pew Research Center poll, which found that 56 percent of Americans view the bombings as justified, suggests that Americans still remain overwhelmingly opposed to an apology.

Domestic backlash towards recognizing and commemorating the victims who died due to the bombings has also likely deterred successive governments from apologizing. For example, in 2010, then-U.S. Ambassador to Japan, John Roos, was criticized for becoming the first U.S. ambassador to Japan to represent the United States at an annual commemoration of the bombings at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. Gene Tibbets, the son of Paul Tibbets Jr., who piloted the Enola Gay plane that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, stated that Roos’ action constituted an “unspoken apology.”

Opposition to recognizing the people killed by the bombings is also demonstrated by the Smithsonian controversy. In the early 1990s, the National Air and Space Museum, a museum of the Smithsonian Institution, planned to include in its upcoming exhibit on the Enola Gay a charred lunch box owned by a child who was 5,000 meters from the Hiroshima bomb’s epicenter. The schoolgirl, Watanabe Reiko, was never found and was presumed dead. The museum also planned to include statements of historians who argued that the bombings were not required to end World War II in its exhibit. Veterans’ groups and the U.S. Senate condemned the planned exhibit on the grounds that it did not sufficiently justify the bombings and portrayed the United States as aggressive and Japan as a victim. In response, the museum sanitized the exhibit and excluded victims’ artifacts from it.

It is likely that U.S. presidents have also been unwilling to atone for the bombings as an American apology may bolster international demands for the U.S. government to provide compensation to all Marshallese affected by U.S. nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands. From 1946-58, the United States conducted over 70 nuclear tests in the then U.S.-controlled Marshall Islands, resulting in the contamination of land, Marshallese suffering from cancer, and, in some cases, their children being born with disabilities.

In response to demands from the Marshallese, the U.S. government provided compensation to some affected Marshallese through the U.S.-government funded Nuclear Claims Tribunal. However, this tribunal has had no funds since 2009, despite the fact that almost $50 million is owed to Marshallese in personal injury claims.

In 2016, regarding Obama’s visit to Hiroshima, which marked the first time a sitting U.S. president visited the city, Donald Trump (now the president himself) proclaimed “that’s fine just as long as he doesn’t apologize.” At the same time, John Bolton — former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations who went on to serve as Trump’s national security adviser — asserted that Obama’s visit was part of an international “shameful apology tour.” As a result, it is not surprising that the Trump administration has shown no interest in apologizing to hibakusha for the atomic bombings. Instead, Trump’s administration is alarmingly contemplating resuming U.S. nuclear testing, which has not occurred since 1992.

In 2016, anti-nuclear activist Setsuko Thurlow, who was 13 when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, publicly stated that hibakusha deserve an apology from the United States. Lamentably, it is highly likely that the U.S. government will not grant hibakusha an apology during Setsuko’s lifetime.

Olivia Tasevski is an International Relations and History tutor at the University of Melbourne, where she completed her Bachelor of Arts (Honours) and Master of International Relations. She specializes in the history of U.S. foreign relations and human rights issues in Indonesia and teaches the subject Nuclear Weapons and Disarmament at the University of Melbourne. She tweets at @OliviaTasevski